Autocracy, Orthodoxy, Nationality. The meaning of concepts. The theory of official nationality

The article examines one of the key concepts of Russian social thought of the first half - the end of the 19th century - the so-called Uvarov triad. Special attention turns to the historical context of its appearance, some little-studied terminological and historiographical nuances of the existence of this formula..

Abstract, keywords and phrases: Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality, S.S. Uvarov, Slavophiles, D.A. Khomyakov.

Annotation

The article examines one of the key concepts of Russian social idea of the first half and the end of the XIX century, so-called Uvarov triad. Specific attention is given to the historical context of its introduction and to some little-investigated terminological, historical and graphical existence nuances of this formula.

Annotation, key words and phrases: Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality, S.S. Uvarov, Slavophiles, D.A. Khomyakov..

About the publication

IN last years the study of Russian conservative thought intensified half of the 19th century century.

However, the desire to understand particular aspects with the involvement of new sources sometimes leads researchers to rather controversial assumptions [See. eg: 6], requiring serious reflection, especially since in historiography there have long been, if not dominant, many unfounded speculative constructions.

This article is devoted to one of these phenomena - the so-called Uvarov triad.

At the beginning of 1832 S.S. Uvarov (1786–1855) was appointed associate minister of public education.

From this time, a rough autograph of his letter has been preserved (on French) To the Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich, which dates back to March 1832. Here for the first time (from known sources) S.S. Uvarov formulates a version of the subsequently famous triad: “... for Russia to strengthen, for it to prosper, for it to live - we are left with three great state principles, namely:

1. National religion.

2. Autocracy.

3. Nationality."

As we see, we are talking about the “remaining” “great principles of state,” where “Orthodoxy” is not called by its proper name.

In the report on the audit of Moscow University, presented to the Emperor on December 4, 1832, S.S. Uvarov writes that “in our century” there is a need for “correct, thorough education,” which should be combined “with deep conviction and warm faith in the truly Russian protective principles of Orthodoxy, autocracy and nationality.” A wider circle of readers learned about this from the book by N.P. Barsukov “Life and works of M.P. Weather." Here we already talk about “truly Russian protective principles” and the need to “be Russian in spirit before trying to be a European by education...”.

March 20, 1833 S.S. Uvarov took over the management of the ministry, and the next day the new minister’s circular proposal, intended for the trustees of educational districts, said the following: “Our common duty is to ensure that public education is carried out in the united spirit of Orthodoxy, autocracy and nationality.”

Note that the text refers only to “public education.”

In the report of S.S. Uvarov “On some general principles that can serve as a guide in the management of the Ministry of Public Education,” presented to the Tsar on November 19, 1833, such logic can be traced.

In the midst of general unrest in Europe, Russia still retained “a warm faith in some religious, moral and political concepts, exclusively belonging to her." In these “sacred remnants of her people lies the entire guarantee of the future.” The government (and especially the ministry entrusted to S.S. Uvarov) must collect these “remains” and “bind with them the anchor of our salvation.” The “remains” (they are also the “beginnings”) are scattered by “premature and superficial enlightenment, dreamy, unsuccessful experiences", without unanimity and unity.

But such a state is seen by the minister only as a practice of the last thirty, and not one hundred and thirty, for example, years (D.A. Khomyakov notes that “the loss of popular understanding was so complete in our country that even those who at the beginning of the 19th century were supporters of everything Russians, and they drew their ideals from antiquity not pre-Petrine, but revered the century of Catherine as real Russian antiquity").

Hence, the urgent task is to establish a “national education” that is not alien to the “European enlightenment”. You can't do without the latter. But it needs to be “skilfully curbed” by combining “the benefits of our time with the traditions of the past.” This is a difficult, state task, but the fate of the Fatherland depends on it [Cit. from: 12, p. 304].

The “main principles” in this report look like this: 1) Orthodox Faith. 2) Autocracy. 3) Nationality.

The education of present and future generations “in the united spirit of Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality” is seen “as one of the most important needs of the time.” “Without love for the Faith of our ancestors,” says S.S. Uvarov, “the people, as well as the private person, must perish.” Note that we are talking about “love of faith,” and not about the need to “live by faith.”

Autocracy, according to S.S. Uvarov, “constitutes the main political condition for the existence of Russia in its present form.” Speaking about “nationality,” the minister believed that “it does not require immobility in ideas.”

This report was first published in 1995.

In the Introduction to the Note of 1843 “Decade of the Ministry of Public Education” S.S. Uvarov repeats and partly develops the main content of the November 1833 report. Now he also calls the main principles “national.”

And in conclusion he concludes that the goal of all the activities of the Ministry is to “adapt ... world education to our people’s life, to our people’s spirit.”

S. S. Uvarov speaks in more detail about nationality, “personality of the people”, “Russian beginning”, “Russian spirit” in the Report to the Emperor on the Slavs dated May 5, 1847 and in the secret “Circular Proposal to the Trustee of the Moscow Educational District” dated May 27 1847 (The circular was first published in 1892). was advancing new era. In 1849 S.S. Uvarov resigned.

We named the sources where they are mentioned various options the so-called Uvarov triad and explanations for them.

All of them were not of a national nature (in terms of powers), but of a departmental nature (remember that in Russia at that time there were 12 ministries and many other departments, and nothing similar to Uvarov’s “principles” was proclaimed there).

There are no “traces of control” on the part of the Emperor over the progress of the “implementation” of S.S.’s ideas. Uvarov as an official imperial ideological program cannot be traced from the sources.

The Uvarov triad did not receive wide public dissemination, much less discussion, during the author’s lifetime, although it had a significant impact on the reform of education in Russia.

But the more than once mentioned “beginnings” themselves are, of course, of great importance, for the initiative came from the Emperor. “This living spirit of right faith and piety,” wrote N.P. Barsukov, - inspired the Anointed of God to put at the forefront of the education of Russian youth: Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality; and the proclaimer of this great symbol of our Russian life is to choose a man who stood fully armed with European knowledge.”

They started talking actively about them decades later, but from positions very far from historical reality.

In 1871, the journal Vestnik Evropy began publishing essays by one of its most prolific contributors, cousin N.G. Chernyshevsky, liberal publicist A.N. Pypin (1833–1904), which in 1873 were published as a separate book entitled “Characteristics of Literary Opinions from the Twenties to the Fifties.” Subsequently, this book was reprinted three more times. In the second and last edition of “Characteristics” during his lifetime, A.N. Pypin left the second chapter, “The Official Nationality,” practically unchanged.

It was in the “Bulletin of Europe” (No. 9 for 1871), in the second essay entitled “Official Nationality”, “the greyhound writer Pypin” (according to the characterization of I.S. Aksakov) for the first time stated that in Russia, since the second half of 1820- In the 1980s, “all state and public life was to be based on the principles of autocracy, Orthodoxy and nationality.” Moreover, these concepts and principles have become “now the cornerstone of the entire national life” and were “developed, improved, raised to the level of infallible truth and appeared, as it were, new system, which was enshrined in the name of the nationality." This “nationality” A.N. Pypin identified it with the defense of serfdom.

In the “official nationality system” constructed in this way, A.N. Pypin never referred to any source.

But through the prism of this “system” he looked at the main phenomena of Russia in the second half of the 1820s - the mid-1850s and made a lot of speculative comments and conclusions. He also brought in the Slavophiles, who were the most dangerous for the liberals of that time, among the supporters of this “system”.

The latter picked up Pypin’s “find”, calling it “the theory of official nationality.” Thus A.N. Pypin and his influential liberal supporters, in fact, for almost a century and a half, right up to the present day, discredited many key phenomena of Russian self-awareness, not only in the first half of the 19th century.

The first (despite his venerable age) to respond to such blatant license in handling the past in “Citizen” was M.P. Pogodin, who emphasized that “they write all sorts of nonsense about the Slavophiles, they make all sorts of false accusations against them and attribute all sorts of absurdities, they invent what did not happen and are silent about what happened...”. Drew the attention of M.P. Pogodin and the “too arbitrarily” used by A.N. Pypin's term "official nationality".

Subsequently A.N. Pypin published a great many of the most various kinds works (according to some estimates, about 1200 in total), became an academician, and for many decades no one bothered to check the validity of the inventions of him and his followers about the “system of official nationality” and the identical “theory of official nationality” and the Uvarov triad.

So, with the “assessments and comments” of A.N. Pypin from the book “Characteristics of Literary Opinions...” “in most cases he completely agreed,” by his own admission, V.S. Soloviev et al.

In the subsequent decades of both the pre-Soviet and Soviet eras, in fact, not a single work on the history of Russia in the 1830s - 1850s was published. could not do without mentioning the “theory of official nationality” as an undoubted generally accepted truth.

And only in 1989, in an article by N.I. Kazakov drew attention to the fact that the artificially constructed A.N. Pypin, of the heterogeneous elements, “theory” is “far in its meaning and practical significance from Uvarov’s formula.” The author showed the inconsistency of Pypin’s definition of “official nationality” as a synonym for serfdom and as an expression of the ideological program of Emperor Nicholas I.

Not without reason N.I. Kazakov also concluded that the government of Emperor Nicholas I had essentially abandoned the idea of “nationality”. The article also included other interesting observations.

Unfortunately, neither N.I. Kazakov, nor other modern experts, do not mention what was done by the son of the founder of Slavophilism A.S. Khomyakova – D.A. Khomyakov (1841–1918). We are talking about three of his works: the treatise “Autocracy. Experience of schematic construction of this concept”, later supplemented by two others (“Orthodoxy (as the beginning of educational, everyday, personal and social)” and “Nationalism”). These works represent a special study of the Slavophile (“Orthodox-Russian”) interpretation of both these concepts and, in fact, the entire range of basic “Slavophile” problems. This triptych was published in its entirety in one periodical in the magazine “Peaceful Work” (1906–1908).

YES. Khomyakov does not refer to A.N. Pypin (his “level” was well known to Russian conservatives), and on the 4th volume of N.P.’s work. Barsukov “The Life and Works of M.P. Pogodin” (St. Petersburg, 1891), where a lengthy quotation was given from the Report of S.S. Uvarov about the audit of Moscow University.

YES. Khomyakov proceeded from the fact that the Slavophiles, having understood the real meaning of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality” and not having time to popularize themselves, did not give a “everyday presentation” of this formula. The author shows that it is precisely this that is the “cornerstone of Russian enlightenment” and the motto of Russian Russia, but this formula was understood in completely different ways. For the government of Nicholas I main part program - “Autocracy” - “is theoretically and practically absolutism.” In this case, the idea of the formula takes on the following form: “absolutism, sanctified by faith and established on the blind obedience of the people who believe in its divinity.”

For the Slavophiles in this triad, according to D.A. Khomyakov, the main link was “Orthodoxy”, but not from the dogmatic side, but from the point of view of its manifestation in everyday and cultural areas. The author believed that “the whole essence of Peter’s reform boils down to one thing - the replacement of Russian autocracy with absolutism,” with which it had nothing in common. “Absolutism,” the outward expression of which was the officials, became higher than “nationality” and “faith.” The created “infinitely complex state mechanism, under the name of the tsar” and the slogan of autocracy, growing, separated the people from the tsar. Considering the concept of “nationality”, D. A. Khomyakov spoke about the almost complete “loss of folk understanding” to the beginning of the nineteenth century and the natural reaction of the Slavophiles to this.

Having determined the meaning of the principles of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality,” D. A. Khomyakov comes to the conclusion that it is “they that constitute the formula in which the consciousness of the Russian historical nationality is expressed. The first two parts make up it distinctive feature... The third, “nationality,” is inserted into it in order to show that such in general, not only as Russian ... is recognized as the basis of every system and all human activity...”

These arguments by D.A. Khomyakov were published during the Time of Troubles and were not truly heard. For the first time, these works were republished together only in 1983, through the efforts of one of the descendants of A. S. Khomyakov - Bishop. Gregory (Grabbe). And only in 2011, the most complete collection of works by D.A. was compiled. Khomyakova.

To summarize, we can state that the Uvarov triad is not just an episode, a stage of Russian thought, the history of the first half of the 19th century. S.S. Uvarov, albeit in a condensed form, drew attention to the fundamental Russian principles, which even today are not only the subject of historical consideration.

As long as the Russian people are alive - and they are still alive, these principles are one way or another present in their experience, memory, in the ideals of their best part. The original Russian power (both ideally and in manifestation) is autocratic (if by autocracy we understand “the active self-consciousness of the people, concentrated in one person”). But in their current state, the people cannot accommodate or bear such power. Therefore, the question of the specific content of the third part of the triad, its name, remains open today. A creative answer can only be given by a churched people and its best representatives.

List of literature / Spisok literature

- Barsukov N.P. Life and works of M.P. Weather. Book 4. St. Petersburg: Publishing house. Pogodinykh, 1891. VIII.

- Bulletin of Europe. 1871. No. 9.

- Tenth anniversary of the Ministry of Public Education. 1833–1843. St. Petersburg: Type-I of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1864. 161 p.

- Reports of the Minister of Public Education S.S. Uvarov to Emperor Nicholas I // River of Times: Book of History and Culture. M.: River of Times: Ellis Luck, 1995. Book. 1. pp. 67–78.

- Addition to the Collection of resolutions of the Ministry of Public Education. St. Petersburg, 1867. 595 p.

- Zorin A.L. Ideology “Orthodoxy – autocracy – nationality” and its German sources // In Thoughts about Russia (XIX century). M., 1996. pp. 105–128.

- Kazakov N.I. About one ideological formula of the Nicholas era / N.I. Kazakov // Context-1989. M.: Nauka, 1989. pp. 5–41.

- Our passing. Journal of history, literature and culture. 1918. No. 2.

- Pogodin M.P. On the issue of Slavophiles // Citizen. 1873. No. 11, 13.

- Against the stream: Historical portraits Russian conservatives of the first third of the 19th century. Voronezh: VSU Publishing House, 2005. 417 p.

- Pypin A.N. Characteristics of literary opinion from the twenties to the fifties: Historical sketches. SPb.: M.M. Stasyulevich, 1873. II, 514 p. (2nd edition, corrections and additions, 1890; 3rd edition, with additional appendices, notes and decree, 1906; 4th edition, 1909).

- Russian socio-political thought. First half of the 19th century. Reader. M.: Publishing house Mosk. Univ., 2011. 880 p.

- Collection of orders for the Ministry of Public Education. T. 1. St. Petersburg: Printing house of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1866. 988, 30 stb., 43 p.

- Solovyov V.S. Works: In 2 volumes. T. 1. M.: Pravda, 1989. 687 p.

- Uvarov S.S. Letter to Nicholas I // New Literary Review. M., 1997. No. 26. P. 96–100.

- Khomyakov D.A. Nationality // Peaceful Labor. 1908. Nos. 10–12.

- Khomyakov D.A. Orthodoxy (as the beginning of educational, everyday, personal and public) // Peaceful Work. 1908. Nos. 1–5.

- Khomyakov D. A. Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality. Montreal: Ed. Brotherhood Rev. Job Pochaevsky, 1983. 231 p.

- Khomyakov D.A. Orthodoxy. Autocracy. Nationality / Comp., entry. Art., note, name. dictionary A.D. Kaplina. M.: Institute of Russian Civilization, 2011. 576 p.

- Khomyakov D.A. Autocracy, experience of schematic construction of this concept // Peaceful Labor. 1906. Nos. 6–8.

- Circular proposal of the Administrator of the Ministry of Public Education to the heads of educational districts to join the management of the ministry // Journal of the Ministry of Public Education. 1834. No. 1. P. XLIХ–L.

- Shulgin V.N. Russian free conservatism of the first half of the 19th century. St. Petersburg: Publishing house "Nestor-history", 2009. 496 p.

Nicholas I wanted new people to replace the rebels - law-abiding, believers, loyal to the sovereign.

S. S. Uvarov, a brilliant scientist, specialist in antiquity, and writer, took on the task of educating a new generation. He developed the concept of “Orthodoxy – Autocracy – Nationality”. Uvarov wrote that “Russia lives and is protected by the spirit of autocracy, strong, philanthropic, enlightened.” And all this is reflected in the nationality - the totality of the changing features of the Russian people. Subsequently, these ideas lost their original pedagogical meaning and became the delight of conservatives and nationalists. Uvarov's concept for a long time was implemented through the system of gymnasiums and universities he created.

He failed to do this for many reasons. The main thing was that the theories of the transformation of society were fundamentally contrary to reality, and the life of Russia and the world around it was inexorably destroying the harmonious ideological schemes for educating a new generation of loyal subjects. The reason for the failure of Uvarov’s efforts was also due to the depravity of the education system itself, which he had been implementing for almost 20 years. Uvarov professed a purely class-based, and therefore, even at that time, unfair principle in education, combined with strict police control over every teacher and student.

Let's look at the source

From a modern point of view, S.S. Uvarov tried to formulate the national idea of Russia, which is still being sought in the daytime with fire. In his “Inscription of the Main Principles” he wrote:

“...In the midst of the rapid decline of religious and civil institutions in Europe, with the widespread spread of destructive concepts, in view of the sad phenomena that surrounded us on all sides, it is necessary to strengthen the fatherland on solid foundations on which the prosperity, strength and life of the people are based; to find the principles that constitute the distinctive character of Russia and belong exclusively to it; to collect into one whole the sacred remains of its people and strengthen the anchor of our salvation on them... Sincerely and deeply attached to the church of their fathers, the Russian from time immemorial looked upon it as a guarantee of social and family happiness. Without love for the faith of their ancestors, the people, like the private person, will agree just as little to the loss of one of the dogmas of ORTHODOXY as to the theft of one pearl from the crown of Monomakh.

Autocracy is the main condition for the political existence of Russia. The Russian colossus rests on it as the cornerstone of its greatness... The saving conviction that Russia lives and is protected by the spirit of autocracy, strong, philanthropic, enlightened, must penetrate the people's education and develop with it. Along with these two national principles there is a third, no less important, no less strong: NATIONALITY... Regarding nationality, the whole difficulty lay in the agreement of ancient and new concepts, but nationality does not force one to go back or stop; it does not require immobility in ideas.

State composition, like human body, changes external view your own as you age: features change with age, but physiognomy should not change. It would be inappropriate to oppose this periodic course of things; it is enough if we keep the sanctuary of our popular concepts inviolable, if we accept them as the main thought of the government, especially in relation to national education. These are the main principles that should have been included in the system of public education, so that it would combine the benefits of our time with the traditions of the past and with the hopes of the future, so that public education would correspond to our order of things and would not be alien to the European spirit.”

As we see, Uvarov and many of his contemporaries were faced with the urgent and still urgent problem of choosing a path for Russia, its place in an alarming, constantly changing world, full of contradictions and imperfections. How not to lag behind others, but also not to lose your own face, not to lose your originality - that’s what worried many, including Uvarov. He proposed his ideological doctrine, the foundations of which are quoted above, and tried to implement his ideals with the help of a powerful lever - the system of state education and upbringing.

Uvarov changed a lot in the education system. The most important thing is that he put the school under strict control government agencies. The main person in the created educational districts was the trustee, who was appointed, as a rule, from retired generals. Under Uvarov, a sharp attack on the rights of universities began. In 1835, a new university charter was adopted, which curtailed their independence. And although the number of gymnasiums increased significantly by the end of Nicholas’s reign, the teaching there became worse. Uvarov consistently reduced the number of objects, throwing out those that awakened thought and forced students to compare and think. Thus, statistics, logic, many branches of mathematics, as well as Greek language. All this was done with the aim of erecting, as Uvarov wrote, “mental dams” - such obstacles that would restrain the influx of new, revolutionary, destructive ideas for Russia. IN educational institutions The spirit of the barracks, depressing uniformity and dullness, reigned. Uvarov established special guards who monitored students day and night, sharply reduced the number of private boarding schools, and fought against home education, seeing it as a source of opposition.

But, as often happened in Russia, even the best intentions of reformers, implemented through the bureaucracy, produce results that are directly opposite to those expected. This is what happened with Uvarov’s undertakings. They turned out to be untenable, and it was never possible to create a “new man” according to Uvarov’s recipes. “Sedition” penetrated Russia and captured the minds of more and more people. This became obvious by the end of the 1840s, when the revolution that began in Europe buried the hopes of Nicholas and his ideologists to preserve Russia as an unshakable bastion of European stability and legitimism. Disappointed Nicholas I not only refused the services of Uvarov and others like him, but openly took a consistent course towards the brutal suppression of all dissent and liberalism, towards maintaining power in the country only with the help of police force and fear. This inevitably doomed Russia to a deep internal crisis, which was resolved in the Crimean War.

In politics, as in all public life, not to move forward means to be thrown back.

Lenin Vladimir Ilyich

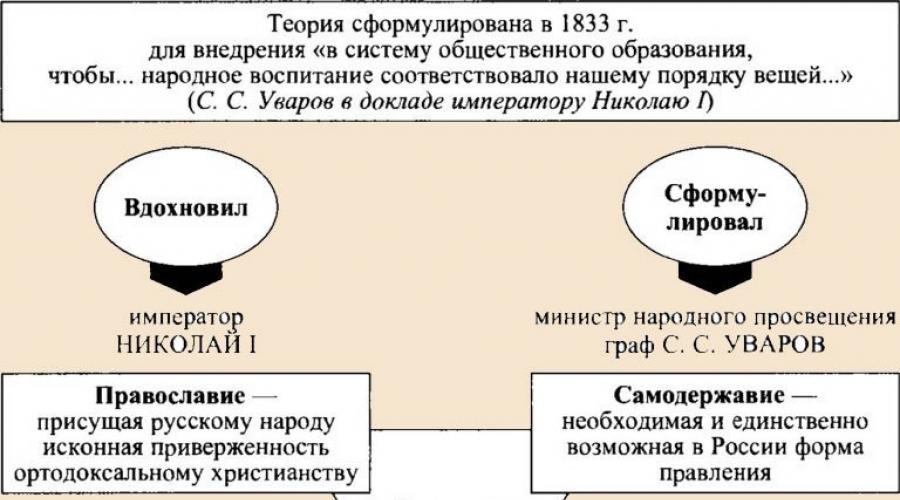

The theory of official nationality arose during the reign of Nicholas 1; this theory was based on the principles Orthodox faith, autocracy and nationality. This ideology was first voiced in 1833 by Count Uvarov, who Russian Empire served as Minister of Public Education.

The main content of the theory

The government of Nicholas 1 sought to create in Russia an ideology that meets the needs of the state. The implementation of this idea was entrusted to S.S. Uvarov, who on November 19, 1833 sent a special report to the emperor entitled “On some general principles that can serve as a guide in strengthening the Ministry.”

In this report, he noted that in Russia there are only three unshakable concepts:

- Autocracy. Uvarov sincerely believed that the Russian people do not share such concepts as “tsar” and “country”. For people, this is all one, guaranteeing happiness, strength and glory.

- Orthodoxy. The people in Russia are religious, and respect the clergy on an equal basis with state authorities. Religion can solve issues that cannot be solved by autocracy.

- Nationality. The foundation of Russia lies in the unity of all nationalities.

General essence new concept boiled down to the fact that the Russian people are already developed, and the state is one of the leading in the world. Therefore, no fundamental changes are necessary. The only thing that was required was to develop patriotism, strengthen autocracy and the position of the church. Subsequently, supporters of this program used the slogan “Autocracy. Orthodoxy. Nationality."

It should be noted that the principles that were set out in the theory of official nationality were not new. Back in 1872 A.N. Pypin in his literary works came to exactly the same conclusions.

Disadvantages of the new ideology

Uvarov's theory was logical and many politicians supported it. But there were also a lot of critics who, for the most part, highlighted two shortcomings of the theory:

- She refuted any creation. In fact, the document stated a fact that is important for Russian people, and what brings him together. There were no proposals for development, since everything was perfect as is. But society needed constructive development.

- Concentration only on on the positive side. Any nationality has both advantages and disadvantages. The official blog theory focused only on the positive, refusing to accept the negative. In Russia there were many problems that needed to be solved; the ideology of the official nationality denied such a need.

Reaction of contemporaries

Naturally, the shortcomings of the new ideology were obvious to everyone. thinking people, but only a few dared to voice their position out loud, fearing a negative reaction from the state. One of the few who decided to express their position was Pyotr Yakovlevich Chaadaev. In 1836, the Telescope magazine published a “Philosophical Letter,” in which the author noted that Russia was actually isolating itself from Europe.

The state created in the country an atmosphere of self-confident nationalism, which was based not on the real state of affairs, but on the stagnation of society. The author emphasizes that Russia needs to actively develop ideological trends and spiritual life of society. The reaction of the government of the Empire was paradoxical - Chaadaev was declared crazy and put under house arrest. This was official position state and personally Emperor Nicholas 1, under whom the theory of the official nationality was long years became the main ideological document in the country. This theory was propagated by everyone who had at least some connection with the state.

Literature

- History of Russia 19th century. P.N. Zyryanov. Moscow, 1999 "Enlightenment"

- Uvarov's reports to Emperor Nicholas 1.

- Official nationality. R. Wortman. Moscow, 1999.

“Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality constitute a formula in which the consciousness of the Russian historical nationality is expressed. The first two parts constitute its distinctive feature... The third, “nationality,” is inserted into it in order to show that such... is recognized as the basis of any system and all human activity...” (thinker, D. A. Khomyakov (1841-1919)

Historical background that contributed to the birth of the triad “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality”

- —

Decembrist uprising and its defeat (1825-1826)

— July revolution in France 1830

— Polish national liberation uprising of 1830-1831

— dissemination of Western European, republican, liberal ideas among the intelligentsia

“at the sight of the social storm that was shaking Europe and the echo of which reached us, threatening us with danger. In the midst of the rapid decline of religious and civil institutions in Europe, with the widespread spread of destructive concepts surrounding us on all sides, it was necessary to strengthen the fatherland on solid foundations on which the prosperity, strength and life of the people are based (Uvarov, November 19, 1833)

- —

pursuit state power to the alienation of the Russian intelligentsia from influence on social life Russia

Even countries seem to need to define a “common vision” for themselves. For NikolaiI (youngest son in the family, who was preparing for a military career, and as a result became emperor in 1825), such a concept became “official patriotism,” which his teacher Count Sergei Uvarov saw in the trinity “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality.”

Nearly two centuries later, this formulation seems to describe the reign of a former spy president as well as a former soldier czar. In any case, Vladimir Putin relies on a very similar ideology.

It should be noted that the meaning of each component of the above trinity has changed in detail in the 21st century. However, they almost exactly define the era of “new Putinism” (or, for optimists, “late Putinism”).

Orthodoxy

One of the most striking images of this year's Victory Parade in Moscow was when Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, by all accounts a Tuvan Buddhist, crossed himself in front of an icon before donning his cap and taking up his duties.

We can interpret this detail as a slight deceit, designed to arouse the sympathy of the crowd, but it seems to me that this would be a mistake in understanding both the personality of Shoigu himself and the role of the Orthodox Church in modern Russia.

Just as before the revolution the ordinary Russian peasant did not share the concepts of “Orthodox” and “Russian,” now religious identity is becoming the cornerstone of patriotic devotion to the Russian state.

Crossing yourself in front of an icon (or donating to the needs of the church) is not necessarily evidence of a person’s religiosity, but rather an expression of his political loyalty to the current government. The flip side of Caesaropapism (a political system in which secular power controls church affairs; mixednews note) is that the secular leader and the political structure he heads willy-nilly merge with church legality.

So when Shoigu is baptized, or when the FSB Academy gets its own church, or when priests bless the troops heading into Ukraine, this does not mean that we are witnessing manifestations of Russian theocracy.

After all, between five and ten percent of Russia's population is Muslim, and other religious communities make up a significant percentage as well. And even among those who associate themselves with the Russian Orthodox Church, only one in ten actually regularly attends church services.

In 1997, the law “On Freedom of Conscience and religious associations”, which stated that Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism and other religions... constitute an integral part of the historical heritage of the peoples of Russia, but, at the same time, the special role of Orthodoxy in the history of Russia, in the formation and development of its spirituality and culture was recognized.

This is the very essence: Orthodoxy is not so much a religion or not just a religion. This is, rather, the basis of all Russian identity. The church itself has already been purchased by the Kremlin. According to Stanislav Belkovsky, she “finally turned into an appendage of the state political-ideological machine.”

So Orthodoxy is not just a religious choice, but a demonstration of political loyalty and recognition of the legitimacy (historical and moral) of the current regime.

Autocracy

The easiest way to say is that Putin is as much an autocrat as Tsar Nicholas I. And in a sense, this will be fair. It’s not that Putin considers himself a monarch chosen from above, but that even Nicholas realized (and was tormented by this) the actual limitations of his power. It would be fairer to say that Putin is no more an autocrat than Nicholas.

Of course, there are many differences between them. Putin is the elected head of state, although the true opposition, in fact, was not allowed to participate in the elections (the Communist Party led by Zyuganov does not count - it has long and comfortably integrated into Putin’s political system). Moreover, despite everything, Putin cannot be called an absolute dictator. He is bound in his actions by both public opinion and the expectations of the elite. There are certain limitations to the way the current regime conducts elections (the Bolotnaya protests are proof of this). Hence the efforts of the official media to create and maintain a cult around the personality of Putin himself, of which, ultimately, the head Russian state and owes its sky-high domestic ratings.

In governing the country, Putin is very dependent on the support of the country's elite, and in this he is similar to Nikolai. Just as Tsar Nicholas I tried to bring German aristocrats closer to him in the hope that they would turn out to be more honest and efficient (they were, but this did not help change the system as a whole), so Putin largely relies on the security forces (who turned out to be no more effective , but even more corrupt). But, be that as it may, for any “autocrat” or “autocrat” the support of the elite is in many ways decisive.

At the heart of every “autocracy” lies the idea of the country’s political superiority. Under the rule of Nicholas, Russia turned into the “gendarme of Europe,” ardently supporting the attempts of other authoritarian regimes to crush the revolutionary processes brewing in them. At the same time, Nicholas's concept of autocracy included the rule of law (no matter how draconian) and the paternal obligations of the ruler towards his subjects.

The modern world is not so easily controlled, however, nowadays Putin shows much less tolerance towards the freedoms of society: laws on " foreign agents", FSB pressure on various kinds of non-governmental organizations, punitive measures against liberal media, etc.

Nationality

In some ways, this concept is both the most crafty and the most familiar. And again, this word should not be understood in the usual ethno-linguistic sense. Even under Nicholas, “narodnost” and “nationality” were defined more as loyalty to the state than as belonging to a particular ethnic group. That is, “Russian nationalism” has more to do with what kind of passport a person has than with his true nationality.

Of course, this is explained by the practical necessity of a multinational state. But this also reflects the historical evolution of Russia, where national identity was formed in conditions of close, sometimes hostile, relationships between the central government and local interests and initiatives.

Under the ethnically chauvinistic Russian regime, it is unlikely that a Tuvan would take the post of defense minister, or a Tatar would take the post of head of the central bank. It is unlikely that key posts in the cabinet would go to Jews, etc.

Thus, in Russia, the concepts of “narodnost” or “nationalism” are associated with historical, cultural and political identity and a person’s desire to accept them. If you are ready to tie the St. George ribbon and follow certain rules and rituals, then it does not matter what your name is - Ivan Ivanovich or Gerard Depardieu.