Russian fabulists. Famous Russian fabulists essay

Read also

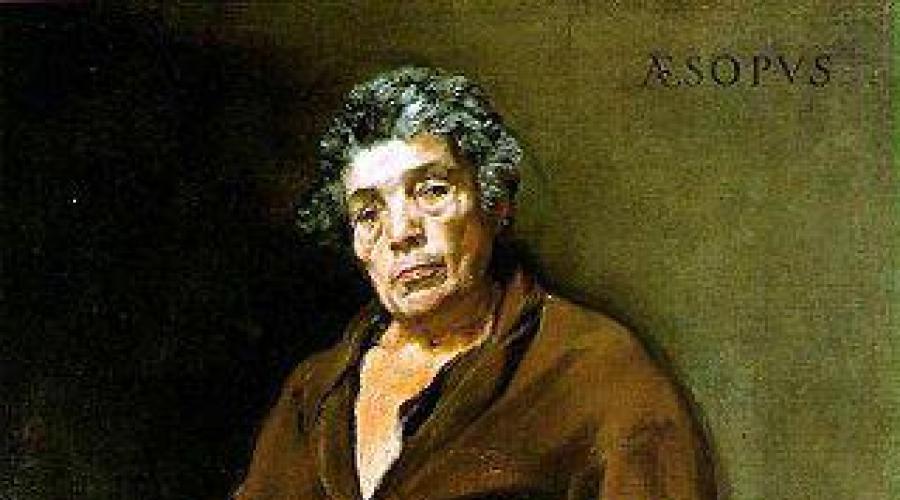

Aesop

6th century BC

Life story

Aesop (Esop) is considered the founder of the fable as a genre, as well as the creator artistic language allegories - Aesopian language, which has not lost its relevance from ancient times to the present day. In the darkest periods of history, when one could lose one’s head for speaking truthfully, humanity did not fall into muteness only because it had Aesopian language in its arsenal - it could express its thoughts, views, protests in stories from the lives of animals, birds, fish .

With the help of fables, Aesop taught humanity the basics of wisdom. “Using animals in the form in which they are still depicted on heraldic coats of arms, the ancients passed on from generation to generation great truth life... - wrote Gilbert Chesterton. - If a knight's lion is fierce and terrible, he is indeed fierce and terrible; If the sacred ibis stands on one leg, it is doomed to stand that way forever.

In this language, structured like a huge animal alphabet, the most ancient philosophical truths are written. Just as a child learns the letter “A” from the word “stork”, the letter “B” from the word “bull”, the letter “B” from the word “wolf”, a person learns simple and great truths from simple and strong creatures - the heroes of fables.” .

And this never-silent humanity, which owes so much to Aesop, still does not know for sure whether such a person really existed, or whether he is a collective person.

According to legend, Aesop was born in the 6th century BC. in Phrygia (Asia Minor), was a slave and then a freedman. For some time he lived at the court of the Lydian king Croesus in Sardis. Later, while in Delphi, he was accused of sacrilege by the priestly aristocracy and thrown from a cliff.

A whole book of funny stories about his life and adventures has been preserved. Despite the fact that Aesop, according to legend, was ugly and hunchbacked, and also foul-mouthed, he became a real hero of folk legends, telling about his courageous actions against the rich and nobility, about his disgrace of the false wisdom of the ruling elite.

The book “Outstanding Portraits of Antiquity” (1984) by the German archaeologist, historian and art critic Hermann Hafner presents a drawing on a drinking vessel made in the 5th century BC. in Athens (kept in the Vatican). It grotesquely depicts a hunchbacked counterpart with a fox, who, judging by her gestures, is telling him something. Scientists believe that the drawing depicts Aesop.

In the same book, Hafner claims that in Athens during the reign of Demetrius of Phalerum (317-307 BC), a statue of Aesop created by Lysippos was placed next to the group of “Seven Wise Men”, which indicates the high veneration of the fabulist and two centuries after his death. It is believed that under Demetrius of Phalerum a collection of Aesop's fables appeared, compiled by a person unknown to us. “In such a compiler, apparently, there was something great and humane,” as Chesterton rightly noted, “something from the human future and the human past...”

A collection of 426 fables in prose has been preserved under the name of Aesop. Among them there are many stories familiar to us. For example, “A hungry fox noticed hanging bunches of grapes on one vine. She wanted to get them, but couldn’t and left, saying to herself they were still green.” Or “The wolf once saw how the shepherds in the hut were eating a sheep. He came close and said, “What a fuss you would make if I did this!”

Writers of different eras gave literary form to the fables from this collection. In the 1st century AD The Roman poet Phaedrus became famous for this, and in the 2nd century the Greek writer Vabrius became famous. In the Middle Ages, the fables of Aesop and Phaedrus were published in special collections and were very popular. Modern fabulists La Fontaine in France, Lessing in Germany, I.I. drew their plots from them. Khemnitser, A.E. Izmailov, I.A. Krylov in Russia.

|

Phaedrus Ancient Roman fabulist. His Latin name was not Phaedrus, but rather Phaeder; inscriptions and ancient evidence testify in favor of this form grammars. Phaedrus lived in the 1st century. according to R. Chronicle; was from a Roman province Macedonia. He probably came to Italy when he was still very young; Judging by the title of his works, he was a freedman of Augustus. Ambition prompted him to take up poetry. He decided to translate into Latin in iambic Aesop's fables, but already in the 2nd book he emerged from the role of imitator and wrote a fable based on a story from the life of Tiberius. The poet's desire to bring themes closer together his works with modernity turned out to be disastrous for him, so how at this time the imperial power was already beginning to persecute freedom literature, and numerous informers greedily took advantage of every opportunity to initiate lese majeste proceedings. Almighty favorite Tiberius, Sejanus, saw in some fables a hint of his person and caused the poet a lot of trouble, maybe even sent him to exile. Under Caligula, Phaedrus probably published the third book of his fable The poet wanted to finish his poetic career with this book, in order to "leave something for development and for their future brothers", but this did not stop him from publishing his fourth and fifth books. Phaedrus probably died around 87 - 88 according to R. Chr. He proudly told one of his patrons declared that his name would live as long as Roman literature was respected, but he counted more on future generations than on his contemporaries, whose attitude towards him he compares with the attitude of a rooster to a pearl grain. Striving exclusively for fame, Phaedrus did not seek any material benefits. His main merit lies in the fact that he introduced Roman literature fables, as an independent department; she used to found only sporadically in the works of various writers. Despite the fabulist's repeated statements about his independence, in his best works he remains only imitator of Aesop. His attempts to compose fables in the spirit of Aesop should be considered unsuccessful. For example, Lessing quite rightly condemned fable 4, 11, which Phaedrus expressively calls his own. Fyodor often imposes the moral of the fable on his reader; sometimes, judging by conclusion, he does not even understand the meaning of the Greek fable he is translating; very often, finally, he moves away from the simplicity of his chosen family poetry and strays into satire. Much more successful are those poems by Phaedrus, where he talks about the events of his time; like, for example, an episode from life of the flutist Princeps (5, 7). Among the undoubted advantages of Phaedrus belongs to his simple, clear and pure language, thanks to which he fables, especially in former times, were diligently read in schools; the only one the disadvantage in this regard is the excessive use of abstract names The iambs of Phaedrus strictly comply with the laws of metrics. Belittle F.'s literary fame was greatly contributed to by such talented imitators him, like Lafontaine and Florian. In the Middle Ages, Phaedrus suffered a peculiar fate: his fables were retold in prose, and these retellings were completely the court chaplain of Henry II of England, Walter, retold it in verse. Only in late XVI table. three ancient manuscripts of Phaedrus himself were found, one of whom died. 30 fables of Phaedrus became known to the scientific world only With early XIX table., when the list of them made by the cardinal was opened Perotti in the 15th century; but even after finding Perotti’s recording, you can’t go far guarantee that we have all Phaedrus. The loss of fables already indicates their distribution among books: in the 1st - 31, in the 2nd - only 8, in the 3rd - 19, in 4th - 25, in the 5th - only 10. F.'s main manuscript - "codex Pitboeanns" (IX century). named after its former owner Nitu, now is in private hands; in 1893 it was published phototypically in Paris. |

Jean Lafontaine

(French Jean de La Fontaine) - famous French fabulist; genus. in 1621 in Château-Thierry, died in 1695.

His father served in the forestry department, and Lafontaine spent his childhood among forests and fields. At the age of twenty he entered the Oratorian brotherhood (Oratoire) to prepare for the clergy, but was more interested in philosophy and poetry.

In 1647, Jean La Fontaine's father transferred his position to him and convinced him to marry a 15-year-old girl. He took his new responsibilities, both official and family, very lightly, and soon left for Paris, where he lived his whole life among friends, admirers and admirers of his talent; He forgot about his family for years and only occasionally, at the insistence of friends, went to his homeland for a short time.

His correspondence with his wife, whom he made the confidant of his many romantic adventures, has been preserved. He paid so little attention to his children that, having met his adult son in the same house, he did not recognize him. In Paris, Lafontaine was a brilliant success; Fouquet gave him a large pension as payment for one poem a month; the entire aristocracy patronized him, and he knew how to remain independent and gracefully mocking, even amid the flattering panegyrics with which he showered his patrons.

The first poems that transformed Jean La Fontaine from a salon poet into a first-class poet were written by him in 1661 and were inspired by sympathy for the sad fate of his friend Fouquet. It was “Elegy to the Nymphs of Vaux” (Elégie aux nymphes de Vaux), in which he ardently interceded with Louis XIV on behalf of the disgraced dignitary. He lived in Paris, first with the Duchess of Bouillon, then, for more than 20 years, at the hotel Madame de Sablière; when the latter died and he left her house, he met his friend d'Hervart, who invited him to live with him. “That’s exactly where I was heading,” was the fabulist’s naive answer.

In 1659-65. Jean La Fontaine was an active member of the circle of “five friends” - Moliere, L., Boileau, Racine and Chappelle, and maintained friendly relations with everyone even after the break between other members of the circle. Among his friends were also Conde, La Rochefoucauld, Madame de Sevigny and others; only he did not have access to the courtyard, since Louis XIV I did not like a frivolous poet who did not recognize any responsibilities. This slowed down La Fontaine's election to the academy, of which he became a member only in 1684. Under the influence of Madame de Sablier La Fontaine, in last years life, became a believer, remaining, however, a frivolous and absent-minded poet, for whom only his poetry was serious. The significance of Jean La Fontaine for the history of literature lies in the fact that he created a new genre, borrowing from ancient authors only the external plot of fables. The creation of this new genre of semi-lyrical, semi-philosophical fables is determined by the individual character of La Fontaine, who sought a free poetic form to reflect his artistic nature.

These searches were not immediately successful. His first work was La Gioconda (Joconde, 1666), a frivolous and witty imitation of Ariosto; this was followed by whole line“fairy tales”, extremely obscene. In 1668, the first six books of fables appeared, under the modest title: “Aesop’s Fables, translated into verse by M. La Fontaine” (Fables d’Esope, mises en vers par M. de La Fontaine); The 2nd edition, which already contained 11 books, was published in 1678, and the 3rd, with the inclusion of the 12th and last book, in 1694. The first two books are more didactic in nature; in the rest, Jean La Fontaine becomes more and more free, mixes moral teaching with the transfer of personal feelings and, instead of illustrating, for example, this or that ethical truth, he mostly conveys some kind of mood.

Jean La Fontaine is least of all a moralist and, in any case, his morality is not sublime; he teaches a sober outlook on life, the ability to use circumstances and people, and constantly depicts the triumph of the clever and cunning over the simple-minded and kind; There is absolutely no sentimentality in it - his heroes are those who know how to arrange their own destiny. But it is not in this crude, utilitarian morality that the meaning of Jean La Fontaine's fables lies. They are great for their artistic merit; the author created in them “a comedy in a hundred acts, bringing to the stage the whole world and all living beings in their mutual relationships.” He understood people and nature; reproducing the mores of society, he did not smash them like a preacher, but looked for the funny or touching in them. In contrast to his age, he saw animals not as mechanical creatures, but as a living world, with a rich and varied psychology. All nature lives in his fables. Under the guise of the animal kingdom, he, of course, draws the human kingdom, and draws subtly and accurately; but at the same time his animal types in highest degree self-possessed and artistic in their own right.

The artistic significance of Jean La Fontaine's fables is also contributed by the beauty of La Fontaine's poetic introductions and digressions, his figurative language, free verse, special art of conveying movement and feelings with rhythm, and in general the amazing richness and variety of poetic form. A tribute to gallant literature was the prose work of Jean La Fontaine - the story “The Love of Psyche and Cupid” (Les amours de Psyché et de Cupidon), which is a reworking of Apuleius’ tale about Cupid and Psyche from his novel “The Golden Ass”.

Ivan Andreevich Krylov

Russian fabulist, writer, playwright.

Born in 1769 in Moscow. Young Krylov studied little and unsystematically. He was ten years old when his father, Andrei Prokhorovich, who was at that moment a minor official in Tver, died. Andrei Krylov “didn’t study science,” but he loved to read and instilled his love in his son. He himself taught the boy to read and write and left him a chest of books as an inheritance. Krylov received further education thanks to the patronage of the writer Nikolai Aleksandrovich Lvov, who read the poems of the young poet. In his youth, he lived a lot in Lvov’s house, studied with his children, and simply listened to the conversations of writers and artists who came to visit. The shortcomings of a fragmentary education affected later - for example, Krylov was always weak in spelling, but it is known that over the years he acquired quite solid knowledge and a broad outlook, learned to play the violin and speak Italian.

He was registered for service in the lower zemstvo court, although, obviously, this was a simple formality - he did not go to Krylov’s presence, or almost did not go, and did not receive any money. At the age of fourteen he ended up in St. Petersburg, where his mother went to ask for a pension. Then he transferred to serve in the St. Petersburg Treasury Chamber. However, he was not too interested in official matters. In the first place among Krylov’s hobbies were literary studies and visiting the theater. These passions did not change even after he lost his mother at the age of seventeen, and worries about caring for him fell on his shoulders. younger brother. In the 80s he wrote a lot for the theater. From his pen came the libretti of the comic operas “The Coffee Shop” and “The Mad Family”, the tragedies “Cleopatra” and “Philomela”, and the comedy “The Writer in the Hallway”. These works did not bring the young author either money or fame, but helped him get into the circle of St. Petersburg writers. He was patronized by the famous playwright Ya. B. Knyazhnin, but the proud young man, deciding that he was being mocked in the “master’s” house, broke up with his older friend. Krylov wrote the comedy "Pranksters", in the main characters of which, Rhymestealer and Tarator, contemporaries easily recognized the Prince and his wife. “The Pranksters” is a more mature work than the previous plays, but the production of the comedy was prohibited, and Krylov’s relationship deteriorated not only with the Knyazhnin family, but also with the theater management, on which the fate of any dramatic work depended.

Since the late 80s, the main activity has been in the field of journalism. In 1789, he published the magazine “Mail of Spirits” for eight months. The satirical orientation, which appeared already in the early plays, was preserved here, but in a somewhat transformed form. Krylov created a caricature of his contemporary society, framing his story in the fantastic form of correspondence between gnomes and the wizard Malikulmulk. The publication was discontinued because the magazine had only eighty subscribers. Judging by the fact that “Spirit Mail” was republished in 1802, its appearance did not go unnoticed by the reading public.

In 1790 he retired, deciding to devote himself entirely to literary activity. He became the owner of a printing house and in January 1792, together with his friend, the writer Klushin, began publishing the magazine "Spectator", which was already enjoying greater popularity.

The greatest success of “The Spectator” was brought by the works of Krylov himself “Kaib”, an oriental story, a fairy tale of the Night, “A eulogy in memory of my grandfather”, “A speech spoken by a rake in a meeting of fools”, “Thoughts of a philosopher about fashion”. The number of subscribers grew. In 1793, the magazine was renamed "St. Petersburg Mercury". By this time his publishers had focused primarily on constant ironic attacks on Karamzin and his followers. The publisher of Mercury was alien to the reformist work of Karamzin, which seemed to him artificial and overly susceptible to Western influences. Admiration for the West, the French language, and French fashions was one of the favorite themes of the young Krylov’s work and the object of ridicule in many of his comedies. In addition, the Karamzinists repulsed him with their disdain for the strict classicist rules of versification, and he was outraged by the overly simple, in his opinion, “common” style of Karamzin. As always, he portrayed his literary opponents with poisonous causticism. Thus, in “A speech in praise of Yermolafide, delivered at a meeting of young writers,” Karamzin was mockingly depicted as a person talking nonsense, or “Yermolafia.” Perhaps it was the sharp polemics with the Karamzinists that pushed readers away from the St. Petersburg Mercury.

At the end of 1793, the publication of the St. Petersburg Mercury ceased, and Krylov left St. Petersburg for several years. According to one of the writer’s biographers, “From 1795 to 1801, Krylov seemed to disappear from us.” Some fragmentary information suggests that he lived for some time in Moscow, where he played cards a lot and recklessly. Apparently, he wandered around the province, living on the estates of his friends. In 1797, Krylov went to the estate of Prince S. F. Golitsyn, where he apparently was his secretary and teacher of his children.

It was for a home performance at the Golitsyns in 1799-1800 that the play “Trumph or Podschipa” was written. In the evil caricature of a stupid, arrogant and evil warrior, Trump was easily discernible Paul I, which the author did not like primarily for his admiration for the Prussian army and King Frederick II. The irony was so caustic that the play was first published in Russia only in 1871. The significance of "Trump" is not only in its political overtones. Much more important is that the very form of “joke tragedy” parodied classical tragedy with its high style and in many ways meant the author’s rejection of those aesthetic ideas to which he had been faithful over the previous decades.

After the death of Paul I, Prince Golitsyn was appointed governor-general of Riga, and Krylov served as his secretary for two years. In 1803 he retired again and, apparently, again spent the next two years in continuous travel around Russia and card game. It was during these years, about which little is known, that the playwright and journalist began to write fables.

It is known that in 1805 Krylov in Moscow showed the famous poet and fabulist I.I. Dmitriev your translation of two fables Lafontaine: "The Oak and the Cane" and "The Picky Bride." Dmitriev highly appreciated the translation and was the first to note that the author had found his true calling. The poet himself did not immediately understand this. In 1806, he published only three fables, after which he returned to dramaturgy.

In 1807 he released three plays at once, which gained great popularity and were performed successfully on stage. These are “Fashion Shop”, “Lesson for Daughters” and “Ilya Bogatyr”. The first two plays were especially successful, each of which in its own way ridiculed the nobles’ addiction to French, fashions, morals, etc. and actually equated gallomania with stupidity, debauchery and extravagance. The plays were repeatedly staged, and “The Fashion Shop” was even performed at court.

Despite the long-awaited theatrical success, Krylov decided to take a different path. He stopped writing for the theater and every year he devoted more and more attention to working on fables.

In 1808, he published 17 fables, including the famous “The Elephant and the Pug.”

In 1809, the first collection was published, which immediately made its author truly famous. In total, before the end of his life, he wrote more than 200 fables, which were combined into nine books. He worked until last days- the last lifetime edition of the fables was received by the writer’s friends and acquaintances in 1844, along with notice of the death of their author.

At first, Krylov's work was dominated by translations or adaptations of La Fontaine's famous French fables ("The Dragonfly and the Ant", "The Wolf and the Lamb"), then gradually he began to find more and more independent plots, many of which were related to topical events in Russian life. Thus, the fables “Quartet”, “Swan”, “Pike and Cancer”, “Wolf in the Kennel” became a reaction to various political events. More abstract plots formed the basis of "The Curious", "The Hermit and the Bear" and others. However, fables written “on the topic of the day” very soon also began to be perceived as more generalized works. The events that gave rise to their writing were quickly forgotten, and the fables themselves turned into favorite reading in all educated families.

Working in a new genre dramatically changed Krylov's literary reputation. If the first half of his life passed practically in obscurity, was full of material problems and deprivations, then in maturity he was surrounded by honors and universal respect. Editions of his books sold in huge circulations for that time. The writer, who at one time laughed at Karamzin for his predilection for overly popular expressions, now himself created works that were understandable to everyone, and became a truly popular writer.

Krylov became a classic during his lifetime. Already in 1835 V.G. Belinsky in his article “Literary Dreams” he found only four classics in Russian literature and put Krylov on a par with Derzhavin ,Pushkin And Griboyedov .

On national character His language and his use of characters from Russian folklore attracted the attention of all critics. The writer remained hostile to Westernism throughout his life. It is no coincidence that he joined the literary society “Conversation of Lovers of Russian Literature,” which defended the ancient Russian style and did not recognize Karamzin’s language reform. This did not prevent Krylov from being loved by both supporters and opponents of the new light style. Thus, Pushkin, to whom the Karamzin direction in literature was much closer, comparing Lafontaine and Krylov, wrote: “Both of them will forever remain the favorites of their fellow citizens. Someone rightly said that simplicity is an innate property of the French people; on the contrary, distinguishing feature in our morals there is some kind of cheerful cunning of the mind, mockery and a picturesque way of expressing ourselves."

In parallel with popular recognition, there was also official recognition. From 1810, Krylov was first an assistant librarian and then a librarian at the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg. At the same time, he received a repeatedly increased pension “in honor of his excellent talents in Russian literature.” Was elected a member Russian Academy, was awarded a gold medal for literary merit and received many other awards and honors.

One of characteristic features Krylov's popularity includes numerous semi-legendary stories about his laziness, sloppiness, gluttony, and wit.

Already celebrating the fiftieth anniversary creative activity fabulist in 1838 turned into a truly national celebration. Over the past almost two centuries, there has not been a single generation in Russia that was not brought up on Krylov’s fables.

Ivan Andreevich Krylov died in 1844 in St. Petersburg.

A person’s acquaintance with a fable occurs at school. This is where we first begin to understand it deep meaning, draw the first conclusions from what we read and try to do the right thing, although this does not always work out. Today we will try to figure out what it is and find out what the form of speech of the fable is.

What is a fable

Before we find out what the fable’s speech form is, let’s figure out what it is. A fairy tale is called a fable small sizes, written in a moralizing manner. Her actors are animals and inanimate objects. Sometimes people are the main characters of fables. It can be in poetic form or written in prose.

A fable is what form of speech? We will learn about this later, but now let's talk about its structure. A fable consists of two parts - a narrative and a conclusion, which is considered to be specific advice, rule or instruction "attached" to the narrative. Such a conclusion is usually located at the end of the work, but can also be given at the beginning of the essay. Some authors also present it as the final word of one of the characters in the fairy tale. But no matter how the reader tries to see the conclusion in a separately written line, he will not be able to do this, since it is written in a hidden form, as a matter of course in connection with the given events and conversations. Therefore, to the question: - you can answer that this is a reasonable and instructive conclusion.

Fable speech form

Continuing to study this, let us dwell on the next question. What is the form of speech of the fable? Most often, the authors of the work turn to allegory and direct speech. But there are also works in the genre of didactic poetry, in a short narrative form. But it must be a work that is complete in plot and subject to allegorical interpretation. There is definitely a morality that is veiled.

Krylov's fables are original. The Russian writer, of course, relied on the works of his predecessors - Aesop, Phaedrus, La Fontaine. However, he did not try to imitate their works or translate them, but created his own original fables. As a rule, he used direct speech and allegory, dialogues.

Famous fabulists

The fable came to us from the times Ancient Greece. From here we know such names as Aesop (the greatest author of antiquity), the second greatest fabulist - Phaedrus. He was the author not only of his own works, but also was involved in translations and adaptations of Aesop's works. IN Ancient Rome Avian and Neckam knew what a fable was. In the Middle Ages, such authors as Steingevel, Nick Pergamen, B. Paprocki, and many other authors were engaged in writing fairy tales with an instructive conclusion. He became famous for his works this genre and Jean La Fontaine (seventeenth century).

Fable in Russian literature

In the 15th and 16th centuries in Russia, those fables that came from the East through Byzantium were successful. Although even before this time, readers had already formed some opinion about what it was. A little later, people began to study the works of Aesop, and in 1731 Cantemir even wrote six fables. True, in this he noticeably imitated the works of the ancient Greek author, but still Cantemir’s works can be considered Russian.

Khemnitser, Sumarokov, Trediakovsky, Dmitriev worked hard to create their own and translate foreign fables. In Soviet times, the works of Demyan Bedny, Mikhalkov, and Glibov were especially popular.

Well, the most famous Russian fabulist was and remains Ivan Andreevich Krylov. The heyday of his work occurred at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The heroes of the works were most often animals and inanimate objects. They act like people, but with their behavior they ridicule the vices of human nature. Many animals represent some kind of character trait. For example, a fox symbolizes cunning, a lion - courage, a goose - stupidity, an owl - wisdom, a hare - cowardice, and so on. Krylov's original, ingenious and perfect fables have been translated into many European and Oriental languages. The fabulist himself made a significant contribution to the development of this genre and literature in general in Russia. This is probably why his sculpture, among other outstanding personalities, took its place on the “Millennium of Russia” monument in the oldest city- Veliky Novgorod.

Summarize

So, we figured out the fable, how it happened, where they lived and what the creators of this genre were called. We found out who the best fabulists in the world were and studied the features of their works. We also know what the structure of this literary masterpiece is and what it teaches. Now the reader knows what to say when given the task: “Explain the concept of a fable.” The form of speech and the special language of these works will not leave anyone indifferent.

FABULORS BEFORE AND AFTER KRYLOV Story and purpose - that is the essence of the fable; satire and irony are its main qualities. V.G. Belinsky A fable - a short moralizing story, often in poetry - existed in ancient times. ANTIQUE Aesop - biographical information about him is legendary. They said that he was an ugly Phrygian slave (from Asia Minor), owned by the simple-minded philosopher Xanthus, whose book learning he more than once put to shame with his ingenuity and common sense. For services to the state he was released, served the Lydian king Croesus, and died a victim of slander by the Delphic priests, offended by his denunciations. It is this legendary hero, Aesop, who is credited with the “invention” of almost all popular fable plots. In Aesop's works, animals speak, think, act like people, and human vices attributed to animals are ridiculed. This literary device is called allegory, or allegory, and after the name of the author it is called Aesopian language. Aesop's fables have come down to us in prose form. Phaedrus (c. 15 BC - c. 70 (?) AD) - slave and later freedman of the Roman emperor Augustus. Published five books of fables in verse Latin. The first fables were written based on Aesopian plots; later, more and more new, “own” things began to appear in them. Babriy (late 1st - early 2nd century) - also made a poetic arrangement of fables into Greek , but in a different poetic meter and style. Nothing is known about his life. 145 of his poetic fables and about 50 more in prose retelling have been preserved. WESTERN EUROPE Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695) - representative of French classicism, a great poet and fabulist. Like Krylov, he did not immediately turn to fables; first he wrote dramatic works and prose. His fables combined ancient plots and a new style of presentation. La Fontaine enriched the language of the fable with class dialects, and the syllable with various poetic styles, giving the presentation the naturalness of colloquial speech. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) - writer, playwright and philosopher of the German Enlightenment. He considered the purpose of the fable to be denunciation and instruction. RUSSIA “In Russia, the main stages in the development of the fable genre were the amusing fable of A.P. Sumarokova, mentor I.I. Khemnitsera, graceful I.I. Dmitrieva, slyly sophisticated IL. Krylova, colorful and household A.E. Izmailova. Since the middle of the 19th century, fable creativity in Russia and Europe has been fading away, remaining in journalistic and humorous poetry. Vasily Kirillovich Trediakovsky (1703-1769) - the first Russian professor at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, a reformer of Russian versification, worked as a translator at the Academy of Sciences, wrote laudatory poems in honor of high-born persons, for which he was elevated to court poets. Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (1711-1765) - a great Russian scientist and poet - the first classic of Russian literature. Translated several of La Fontaine's fables. Alexander Petrovich Sumarokov (1717-1777) - the founder of Russian classicism, in his work gave examples of almost all poetic genres, including fables. His “Proverbs” for a long time determined the poetic form for the Russian fable. Denis Ivanovich Fonvizin (1743-1792) - author of the famous plays “The Brigadier” and “The Minor”, in his youth he translated the fables of the Danish writer Ludwig Holberg into Russian. Gabriel Romanovich Derzhavin (1743-1816) - the fable genre appeared during his late work, in the 1800s. He usually wrote fables based on original rather than borrowed plots, and responded to specific topical events. Ivan Ivanovich Dmitriev (1760-1837) - in his youth - an officer, in his old age - a dignitary, Minister of Justice. Derzhavin's younger friend and Karamzin's closest comrade. His “Fables and Tales” immediately became a recognized example of this style. Ivan Andreevich Krylov (1769-1844) became known to all readers of Russia immediately after the first collection of his fables was published in 1809. Krylov used stories that came from antiquity from Aesop and Phaedrus. Krylov did not immediately find his genre. In his youth he was a playwright, publisher and contributor to satirical magazines. Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky (1783-1852) - studied fables in his youth, translated fables for self-education and home teaching. In 1806 he translated 16 fables from La Fontaine and Florian. Zhukovsky wrote a large article on the first edition of Krylov's fables, where he placed Krylov the fabulist next to Dmitriev. Kozma Prutkov (1803-1863) is a pseudonym under which a team of authors hides: Alexey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, brothers Vladimir, Alexander and Alexey Zhemchuzhnikov. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy (1828 - 1910) - a great Russian writer, was also... a school teacher. In the early 60s, he first opened a school for peasant children on his estate. Tolstoy wrote four “Russian books for reading,” which included poems, epics and fables. Sergei Vladimirovich Mikhalkov (born 1913) - poet, playwright, famous children's writer. The fable genre appeared in Mikhalkov’s work at the end of the Great Patriotic War.