The first icons in Rus'. Famous icon painters

Read also

Nowhere has icon painting reached such development as in Rus', nowhere has it created so many masterpieces and has become over the centuries the favorite form of fine art of an entire people.

The cult of the icon (from the Greek eikon - image, image) originated in the 2nd century. and flourished in the 4th century; The oldest surviving icons date back to the 6th century. The icon should be considered not as an image identical to the Divine, unlike pre-Christian idols, but as a symbol that allows spiritual communion with the “original” (archetype), that is, penetration into the supernatural world through an object of the material world.

The icons were made initially using the technique of encaustic (wax painting), then with tempera and, in rare cases, mosaics, and later (mainly from the 18th century) with oil painting. The icon became especially widespread in Byzantium; original schools of icon painting arose in Coptic Egypt and Ethiopia, in the South Slavic countries, and in Georgia. The ancient Russian icon acquired real artistic brightness and originality.

Based on archaeological excavations, it has been established that working with paints was known in Ancient Rus' even before the adoption of Christianity. This is evidenced by the discovery of a pestle for rubbing paints, discovered in an excavation at the site of the ancient Saransk settlement, where the city of Rostov the Great was later founded. But the technology of painting and the binders on which the paint was rubbed are not yet known.

The icon consists of four to five layers, arranged in the following order: base, primer, paint layer, protective layer. The icon may have a frame made of metals or any other materials.

The first layer is the base; most often it is a wooden board with a fabric called pavoloka glued to it. Sometimes the board is without pavilion. Very rarely, the base for works of yolk tempera was made only from canvas. The reason for this phenomenon is obvious. Wood, and not stone, served as our main building material, so the overwhelming majority of Russian churches (9/10) were wooden. With their decorativeness, ease of placement in the church, the brightness and durability of their colors (ground on egg yolk), icons painted on boards (pine and linden, covered with alabaster primer - “gesso”) were perfectly suited for the decoration of Russian wooden churches. It was not without reason that it was noted that in Ancient Rus' the icon was the same classical form of fine art as a relief in Egypt, a statue in Hellas, and a mosaic in Byzantium.

The second layer is soil. If the icon is painted in a late manner, combining tempera with paints on other binders (mainly oil), and the layers of primer are colored (color pigments are used, rather than traditional chalk or plaster), then it is called “primer”. But in yolk tempera, which prevailed in icon painting, the ground is always white. This type of soil is called gesso.

The third layer is colorful. The paint layer consists of various colors sequentially applied to the ground. This is the most essential part of a work of painting, since it is with the help of paints that the image is created.

The fourth is a protective (or cover) layer of drying oil or oil varnish. Very rarely, chicken egg white was used as a material for the protective layer (on Belarusian and Ukrainian icons). Currently - resin varnishes.

The frames for the icons were made separately and secured to them with nails. They come in metals, embroidered fabrics, and even carved wood, covered with gesso and gilding. They covered not the entire pictorial surface with frames, but mainly the halos (crowns), background and fields of the icon, and less often - almost its entire surface with the exception of images of heads (faces), hands and feet.

For many centuries in Rus' they painted using the yolk tempera technique; Nowadays the terms “egg tempera” or simply “tempera” are used.

Tempera (from the Italian “temperare” - to mix paints) is painting with paints, in which the binder is most often an emulsion of water and egg yolk, less often - from vegetable or animal glue diluted in water with the addition of oil or oil varnish. The color and tone in works painted with tempera are incomparably more resistant to external influences and retain their original freshness much longer compared to oil painting paints. The yolk tempera technique came to Russia from Byzantium at the end of the 10th century along with the art of icon painting.

Until the end of the 19th century, Russian icon painters, speaking about the process of mixing pigment with a binder, used the expression “rub paint” or “dissolve paint.” And the paints themselves were called “created”. Since the beginning of the 20th century, only paints made from gold or silver powders mixed with a binder (created gold, created silver) began to be called created. The rest of the paints were simply called tempera.

Icons in Rus' appeared as a result of the missionary activity of the Byzantine Church at a time when the significance church art was experienced with particular force. What is especially important and what was a strong internal motivation for Russian church art is that Rus' accepted Christianity precisely in the era of the revival of spiritual life in Byzantium itself, the era of its heyday. During this period, nowhere in Europe was church art as developed as in Byzantium. And at this time, the newly converted Rus' received, among other icons, as an example of Orthodox art, an unsurpassed masterpiece - the icon of the Mother of God, which later received the name of Vladimir.

Rostov-Suzdal school.

Rostov-Suzdal and Zalesskaya Rus' were in ancient times vast lands from the Oka and Volga to the White Lake. These lands became the second center of Russian statehood and culture after Kyiv. In the very center of Rus', over the course of three centuries, from the 10th to the 13th, the cities of Rostov Veliky, Murom, Suzdal, Vladimir, Belozersk, Uglich, Kostroma, Tver, Nizhny Novgorod, and Moscow arose.

The icons painted in Rostov the Great represent it as a center, a kind of academy for painters of North-Eastern Rus'. They confirm the significance and vivid originality of national Central Russian ancient painting and its important role in public art.

The icons of the Rostov-Suzdal school, even at the first acquaintance, amaze us with the brightness and purity of light, the expressiveness of the strict design. They are characterized by a special harmony of a rhythmically constructed composition, soft warm shades colors.

The oldest of the Suzdal icons, the Maksimovskaya Mother of God, was painted in 1299 by order of Metropolitan Maxim in connection with the transfer of the metropolitan see from Kyiv to Vladimir. The Mother of God is depicted full-length with a baby in her arms. The icon has significant losses of ancient painting, but the unusually expressive silhouette and smoothly running lines of the drawing speak of the very high skill of its creators.

Works of painting from the 14th century - the time of the struggle against the Mongol-Tatars - bear the features of the time, their images are full of deep mournful power. They found expression in the icon of the Virgin Mary (14th century). It is characteristic that even the clothing of the Mother of God - the maforium - with its almost black color symbolizes the depth of sadness.

The 15th century is rightly considered the heyday of ancient Russian painting. In the traditions of the Rostov-Suzdal school, one of the masterpieces was painted in the 15th century - an icon depicting the Feast of the Intercession. This holiday was introduced by Andrei Bogolyubsky and became especially popular in the Vladimir-Suzdal land. The central image of this work is the Mother of God, covering people with her cover, protecting them from harm. This work is full of peaceful harmony. This impression is created by a balanced composition, a color scheme built on the relationships of light brown, red and white color shades.

In the 15th century, hagiographic icons, in which the image of a saint is framed with stamps with scenes from his life, became especially widespread. This is how the icon of St. Nicholas (16th century) was made, a saint especially popular in Rus'. This icon is striking in its richness of pink, light green, light brown subtle shades, next to blue and red spots on a white background. This richness of color gives the icon freshness and sonority.

The 16th century, when the idea of statehood grew stronger, was characterized by strict, sublime images. At this time, the icon of the Mother of God Hodegetria (in Greek - “warrior”) was painted. Along with such works, there are others; in them one can feel a living folk understanding of the images and their interpretation.

In the icon of the Annunciation, the artist introduces an image of swans, which in popular belief were associated with the image of a virgin bride.

From the 2nd half of the 16th century, the composition of icons began to become more complex. This trend is gradually increasing, and in the 17th century the artist strives to convey in as much detail as possible the legend underlying this or that iconic image. Thus, the “Descent into Hell” icon is not only very detailed, but for greater persuasiveness it is supplemented with inscriptions. In the underworld, next to the demons personifying human sin, there are inscriptions: “theft,” “fornication,” and “despair.”

At the end of the 17th century, features appeared in Russian icon painting that indicated the approach of the era of realistic painting. Artists strive to paint icons in a manner close to realistic, conveying the volume of faces, figures, and environment. It is these features that characterize the icon of Vladimir Mother of God late 17th century.

All these icons of the Rostov-Suzdal school amaze us either with the brightness, freshness and harmony of the artistic structure, or with the complexity and entertaining nature of the narrative, opening us a window into the past, giving us the opportunity to come into contact with the rich and in some ways not fully understood world of our ancestors.

Moscow school.

The Moscow school took shape and developed intensively during the era of the strengthening of the Moscow principality. Painting of the Moscow school in the 14th century. represented a synthesis of local traditions and advanced trends in Byzantine and South Slavic art (the icons “Savior’s Ardent Eye” and “Savior’s Envelopment”, 1340, Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin). The heyday of the Moscow school in the late 14th - early 15th centuries. associated with the activities of outstanding artists Feofan the Greek, Andrei Rublev, Daniil Cherny. The traditions of their art were developed in the icons and paintings of Dionysius, which attract attention with their sophistication of proportions, decorative festivity of color, and balance of compositions.

The Rostov-Suzdal school, known in Rus' since pre-Mongol times, served as the soil on which Moscow painting developed and took shape in the 14th-16th centuries.

It existed for a long time next to Rostov-Suzdal, but the final dissolution of Rostov-Suzdal painting in the new Moscow direction did not occur. The originality of the first is obvious, and even in the 16th century their works remain true to their traditions.

When did the Moscow school of painting arise?

This is very difficult to establish, since at first the art of Moscow was similar to the art of the Vladimir-Suzdal land, just as the history of Moscow itself merged with its history.

Perhaps the origin of the Moscow school can be associated with such icons of Central Russian origin, such as, for example, “Boris and Gleb” of the early 14th century. Royally majestic, slender and graceful, these young warriors in magnificent clothes, with a sword and a cross in their hands.

Already in the early Moscow icons, the colors complement each other, and the beauty of their dimensional consistency, and not in contrasts. And the linear rhythm of Moscow icon painting is also softly but confidently coordinated in measured sound, without the effects that, for example, the juxtaposition of the vertical with the horizontal gives.

By the beginning of the 15th century, Moscow occupied an exceptional position in Eastern Europe, both politically and culturally. The Moscow principality grew stronger and grew. Artists from many countries flocked to Moscow, for whom it became one of the largest cultural centers. This is how Theophanes the Greek, who had already become famous in Novgorod, ended up in Moscow.

Perfection artistic techniques Feofan - the legacy of a very ancient culture that had long since reached its zenith - was especially important for the final formation of the art of a young power, but already aware of its global significance.

In Moscow, perhaps under the influence of the Moscow pictorial tradition, Feofan showed in his compositions less passion, less dynamism, but more than in Novgorod, majestic solemnity. This is evidenced by what he wrote. central figures Deesis tier of the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral, among which the figure of Mary is especially attractive with its picturesque perfection. No other of his Moscow works have survived.

In addition to Feofan himself, they worked on the painting of the Annunciation Cathedral under his general leadership: “Prokhor the elder from Gorodets, and the monk Andrei Rublev.”

Andrei Rublev was already revered during his lifetime for his outstanding skill, but true fame came to him after his death, and not immediately. But this glory turned out to be indisputable.

The discovery of Rublev’s “Trinity” made a stunning impression; everyone was filled with boundless admiration: one of the most significant, most spiritual creations of world painting was being released from the prison that had hidden it for so long.

“Trinity” served as the foundation for recreating the creative individuality of Andrei Rublev. And the idea was even expressed that it was this particular Rublev masterpiece that most likely provides the key to understanding the beauties of all ancient Russian painting.

All of Rublev's painting sounds like a delightful symphony, like a lyrical verse about universal brotherly affection. How much joy is generously prepared for us here through the means of painting alone, so that before this creation of Rublev, we are indeed ready to agree with Leonardo Da Vinci, who said that painting is the queen of the arts.

These feelings, these joys arise in the contemplation of Rublev’s “Trinity”, even if you do not know what, in essence, its plot is. The icon, in marvelous colors and images, glorifies brotherhood, unity, reconciliation, love, and with its very beauty proclaims hope for the triumph of these good principles.

In Rublev’s work, ancient Russian pictorial culture found its brightest, most complete expression, and his “Trinity” was destined to serve as a beacon for all subsequent Russian icon painting, until this art itself lost its fulness. The stamp of Rublev's genius is on many works of art, of which the Russian people have the right to be proud.

A number of excellent Moscow icons of the first decades of the 15th century testify to the general flourishing of painting in the Rublev era. One of the greatest masters, whose names have not reached us, was the author of the icon of the Archangel Michael from the Archangel Cathedral in Moscow and which, in its artistic merits, can be ranked among the highest achievements of ancient Russian painting. Moreover, what triumphs in this icon is not the principle of bright joy or pacifying sincerity, but the epic, heroic.

Archangel Michael here is not a meek, thoughtful angel with a poetically bowed head, but a menacingly erect young warrior, with a sword in his hands, breathing courage. It was not for nothing that he was considered the leader of the heavenly army, the conqueror of Satan and the patron of Russian princes. This is no longer a sweet dream of a well-ordered world, but the embodiment of military valor and the will to fight.

The entire composition in its linear and colorful rhythm is dynamic, everything in it is seething, as if obeying some force that appears in the gaze of the winged guardian of the Russian land.

...The torch of Russian art, so highly raised by Rublev, passes by the end of the century into the hands of his worthy successor, Dionysius. His frescoes of the Ferapontov Monastery are a monument of ancient Russian art. His compositions have such light elegance, such high decorativeness, such exquisite grace, such sweet femininity in their rhythm, in their gentle sound, and at the same time such solemn, strictly measured, “slowness” that corresponded to the court ceremonial of the Moscow of that time. In this measuredness and restraint, Dionysius displays artistic wisdom, already appreciated by his contemporaries. The turns of the figures are barely indicated, the movements sometimes freeze in one gesture or even a hint of a gesture. But this is enough, because the integrity and beauty of his compositions are based on the absolute internal balance of all parts. And as P.P. Muratov rightly says, “after Dionysius, ancient Russian painting created many beautiful works, but Dionysian dimension and harmony were never returned to it.”

The last great flap of the wings of ancient Russian creativity.

Stroganov school.

The name “Stroganov school” arose due to the frequent use of the family mark of the Solvychegodsk merchants Stroganovs on the back of the icons of this movement, but the authors of most of the works of the Stroganov school were Moscow royal icon painters, who also carried out orders from the Stroganovs - connoisseurs of subtle and sophisticated craftsmanship. The icons of the Stroganov school are characterized by small sizes, miniature writing, rich, dense color scheme based on halftones, enriched by the widespread use of gold and silver, fragile delicacy of the characters’ poses and gestures, complex fantasy of landscape backgrounds.

Novgorod school.

The ancient monuments of Novgorod painting have been most fully preserved. Some works show influences Byzantine art, which speaks of the broad artistic connections of Novgorod. The usual type is a motionless saint with large facial features and wide open eyes. For example, “St. George”, Armory Chamber, Moscow; double-sided icon with images Savior Not Made by Hands and Adoration of the Cross, late 12th century, Tretyakov Gallery.

The glory of the “Novgorod letters” - icons of the Novgorod school - was so great that many connoisseurs considered almost all the best ancient Russian icons to be Novgorod, and some researchers even tried to attribute Rublev and Dionysius to it.

These attempts were not justified. But there is no doubt that in the 15th century the Novgorod school reached its peak, which “leaves behind everything that was created before.” (I.V. Alpatov)

In Novgorod painting, almost from its inception and in all subsequent centuries, the folk principle manifests itself with special force, with special persistence. It will broadly reflect the practical – economic attitude towards the functions and meanings of saints.

The close intertwining of divine forces with the forces of nature and its benefits, inherited from paganism, with everyday life, has long left its mark on the ancient Russian worldview.

The icon painter never painted from life; he sought to capture an idea. Novgorod painting is especially characterized by the desire to make the idea extremely clear, truly tangible, and accessible.

Among the earliest Novgorod icons that have come down to us there are masterpieces of world significance. Such, for example, is “Angel of Golden Hair,” probably written at the end of the 12th century. How tall pure beauty in this unforgettable image!

In the icon of the Novgorod school “Assumption” (13th century), some figures of the apostles literally shock us with the vital truth of those deep experiences that were captured in them by an inspired artist unknown to us. Often the artist depicted completely real people, while typical representatives of the ruling Novgorod elite, with the highest heavenly forces. This is a significant phenomenon in ancient Russian painting, very characteristic of the Novgorod school with its desire for concreteness and truthful expressiveness. Thanks to this, we can clearly imagine the appearance of the then noble Novgorodian.

Novgorod icons are very emotional. Thus, in the icons “The Dormition of the Virgin Mary”, with stunning power, the artist conveyed the great drama of death, the all-consuming human grief. The same theme found its expression in the famous icon “Entombment” (2nd half of the 15th century).

Novgorod icons are beautiful for their color contrasts. In them, each color plays on its own, and each enhances the other in mutual opposition. Compositions of Novgorod painting, no matter how complex they may be - one-, two-, three-figure or multi-subject, narrative character- they are all simple, perfectly inscribed in the plane and consistent with their shapes. All elements are distributed evenly and according to their importance. They are neither overly busy nor empty. The background spaces between individual images take on beautiful shapes, playing a large role in the composition. Figures, mountains, trees are often arranged symmetrically. With this the compositions were closed and received complete completion. At the same time, this symmetry was broken by the turns of the figures, the tilts of their heads, and the various shapes of mountains, platforms, buildings, trees and other images.

Other schools of icon painting.

Volga school.

Icons of the Volga region are characterized by the following features: energetic, clear structure, dark, deep-sounding tones. The Volga region origin of the icon reveals a special predilection for water landscapes. There are four of them. Three show lush dark waters playing with steep waves. On the fourth there are quiet waters, a sandy shore, where a miracle occurs in broad daylight: a traveler with a white sack on his shoulder comes ashore from the open huge mouth of a fish. This icon of St. Nicholas of Zaraisky with his life (16th century).

The “Entombment” icon (late 15th century) is interesting. The figures of the characters are arranged in clear horizontal rows parallel to the tomb with the body of Christ. As if repeating these horizontal lines, in the background there are ledges of hills, diverging from the center to the sides. The figure of Mary Magdalene with her arms raised high seems to personify hopelessness and despair.

In the icon " Last Supper"(late 15th century) the dramatic situation is conveyed by the icon painter extremely expressively: frozen in various poses, with different hand gestures, the apostles are depicted around a white oval table. On the left, at the head, sits Christ, to whom the outer apostle fell in an expressive movement.

Yaroslavl school.

The Yaroslavl icon painting school arose at the beginning of the 16th century. during the period of rapid growth of the city's population and the formation of the merchant class. The works of Yaroslavl masters from the early 13th century have reached us, works from the 14th century are known, and in terms of the number of surviving monuments of painting from the 16th and 17th centuries. The Yaroslavl school is not inferior to other ancient Russian schools. The works of Yaroslavl masters carefully preserved the traditions of the high art of Ancient Rus' until the very middle of the 18th century. At its core, their painting remained faithful to that great style, the principles of which were formed in ancient times and developed for a long time in miniature painting. Along with “petty” images, Yaroslavl icon painters back in the 18th century. They also wrote compositions in which the love for large masses, for strict and laconic silhouettes, for a clear and clear structure of scenes in stamps is palpable in the same way as in the works of masters of the 15-16 centuries. Works of Yaroslavl masters of the second half of the 17th - early 18th centuries. For a long time they were recognized in Russia as examples of old national art. They were collected by admirers ancient icon painting- Old Believers, were carefully studied by the artists of Palekh and Mstera, who continued in the 19-20 centuries. paint icons in the traditions of Russian medieval painting.

One of the oldest icons that has come down to us is “Our Lady of the Great Panagia.” IN decorative design The use of gold plays an important role in the icon, giving the image the impression of majestic beauty and unearthly splendor. The rhythmic construction of the icon also uses the activity of the white color, skillfully used in the writing of the faces.

The emotional intensity of the image is characteristic of the icon “Savior Not Made by Hands” (13th century). It is enhanced thanks to the rich, major painting of the background - the board is designed in bright yellow and red tones of several shades.

Nizhny Novgorod school.

One of the interesting icons of Nizhny Novgorod origin is “The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elijah with the Life” (14th century). It is written broadly and freely. Life scenes are full of movement, gestures are expressive. The richest variety of individual characteristics of the characters. The faces are painted in dark sankir: free writing in bright white marks the expressiveness of the facial shape and the sharpness of the gaze. The artist concentrates attention on the main thing - the state of mind, impulse, expression of spirit; There is tension in the icon, a kind of concentrated state of comprehension of the truth and reflection.

The icon “The Miracle of Dmitry of Thessalonica with the Life” (first half of the 16th century) was made in the same manner - the same characteristic graphic clarity of the silhouette and bright rich colors that distinguish Nizhny Novgorod monuments of the 14th-16th centuries.

Tver school.

The Tver school of icon painting developed in the 13th century. The icons and miniatures of the Tver school are characterized by a severe expressiveness of images, tension and expression of color relationships, emphasized linearity of writing. In the 15th century its previously characteristic orientation towards the artistic traditions of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula intensified.

Pskov scale.

The Pskov school developed during the period of feudal fragmentation and reached its peak in the 14th-15th centuries. It is characterized by increased expression of images, sharpness of light highlights, and impasto brush strokes (icons “The Cathedral of Our Lady” and “Paraskeva, Varvara and Ulyana” - both 2nd half of the 14th century, Tretyakov Gallery). In painting, the collapse of the Pskov school began at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Icon painting played an important role in Ancient Rus', where it became one of the main forms of fine art. The earliest ancient Russian icons had the traditions, as already mentioned, of Byzantine icon painting, but very soon in Rus' their own distinctive centers and schools of icon painting arose: Moscow, Pskov, Novgorod, Tver, Central Russian principalities, “northern letters”, etc. Their own Russian saints also appeared , and their own Russian holidays (Protection of the Virgin Mary, etc.), which are clearly reflected in icon painting.

The artistic language of the icon has long been understandable to any person in Rus'; the icon was a book for the illiterate. The word “icon” itself translated from Greek meant image, image. Most often they turned to the images of Christ, the Mother of God, and saints, and also depicted events that were considered sacred.

And yet, even in this state, the picturesque ensemble of Sophia of Kyiv amazes with the grandeur and unity of design, embodying the world of ideas of medieval man. The appearance of the saints in the mosaics of Sophia of Kyiv is close to the canon developed in Byzantine painting: an elongated oval face, a straight long nose, a small mouth with a thin upper and plump lower lip, huge, wide open eyes, a stern, often stern expression. However, some saints, and especially the saints in the apse, give the impression of portraiture. In general, despite its incomplete preservation, the saint’s rank with echoes of Hellenistic portraiture in the faces, with a clear constructiveness of forms and sophistication of colors is one of the most strong parts decorative ensemble.

Many works of easel painting were created in the 11th century. The Kiev-Pechersk Patericon even retained the name of the famous Russian icon painter of the 11th - early 12th centuries. Pechersk monk Alimpiy, who studied with Greek masters. Contemporaries said about the monk-painter that he “was very clever at painting icons”; icon painting was the main means of his existence. But he spent what he earned in a very unique way: with one part he bought everything that was necessary for his craft, he gave the other to the poor, and the third he donated to Pechersky Monastery. Most of the works from this period have not reached us.

Icons of Vladimir-Suzdal masters of the 12th century. became known in recent years after they were cleared by the Central State Restoration Workshops. Some icons are still very close in style to the Kyiv monuments of the 11th century. Such icons include a horizontally extended icon with a shoulder-shaped image of the “Deesis” from the Moscow Assumption Cathedral (Christ, the Mother of God and John the Baptist). The famous Yaroslavl Oranta, which came to Yaroslavl from Rostov, is also connected with Kyiv artistic traditions. The monumental, majestic figure of the oranta is close in proportions to the figures in Kyiv mosaics. The monumental, solemn icon of Dmitry of Thessalonica, (to the 12th century) brought from the city of Dmitrov, with its ideal correctness, symmetry and “sculptural” modeling of a very light face, resembles the Yaroslavl oranta. Apparently, the icon of George from the late 12th century to the early 14th century also belongs to the Vladimir-Suzdal school. The artist also created here the image of a warrior, but younger, with a beautiful, expressive face. For more full characteristics pre-Mongol Vladimir-Suzdal painting, it is necessary to dwell on one icon of the late 12th century, sharply different from all previous ones. This is an icon of Our Lady of Belozersk, which is a kind of reworking of the type of Our Lady of Vladimir. The icon, created on the northern outskirts of the Vladimir-Suzdal land by a folk artist, is distinguished by its monumentality and deeply emotional interpretation of the image of a mournful mother. Particularly expressive is the look of the huge eyes fixed on the viewer and the painfully twisted mouth. In the image of Christ - a youth, with an ugly face, a large forehead, a thin neck and long legs, bare to the knees, there are features of life observation, sharply captured details. The entire image as a whole is distinguished by the flatness and angularity of the pattern. The icon is made on a silver background in a restrained and gloomy palette. On its blue fields there are medallions with chest-length images of saints with Russian types of faces, written in a broader pictorial manner on pink and blue backgrounds.

In connection with the fragmentation of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality into a number of small principalities, local schools began to emerge in the main cities of these principalities, partially continuing the traditions of Vladimir-Suzdal painting (Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Moscow, Rostov, Suzdal, etc.).

Speaking about the process of creating an icon, it should be noted the high complexity and subtlety of the work. To begin with, a board (most often made of linden) was skillfully selected, onto the surface of which hot fish glue (prepared from the bubbles and cartilage of sturgeon fish) was applied, and a new canvas-pillar was tightly glued. Gesso (the basis for painting), prepared from ground chalk, water and fish glue, was applied to the curtain in several stages. The gesso was dried and polished. Old Russian icon painters used natural dyes - local soft clays and hard precious stones brought from the Urals, India, Byzantium and other places. To prepare paints, stones were crushed into powder, a binder was added, most often yolk, as well as gum (water-soluble resin of acacia, plum, cherry, cherry plum). Icon painters cooked drying oil from linseed or poppy oil, which they used to cover the painting of icons.

Unfortunately, the ancient icons have come down to us greatly altered. The original beautiful painting was hidden by a film of drying oil, darkened by time, which was used to cover the finished icon in the Middle Ages, as well as several layers of later renovations of the icon.

Among the earliest Novgorod icons that have come down to us there are masterpieces of world significance. Such, for example, is “The Golden Haired Angel,” probably written at the end of the 12th century. In all likelihood, this is a fragment of the Deesis order. The deep spirituality of the sad face with huge eyes makes the image of the icon enchantingly beautiful. What high, pure beauty in this unforgettable image! The stamp of Byzantium is still clear and something truly Hellenic shines in the beautiful oval face with a delicate blush under wavy hair trimmed with gold threads. But the sadness in the eyes, so radiant and deep, all this sweet freshness, all this exciting beauty, isn’t it already a reflection of the Russian soul, ready to realize its special destiny with its tragic trials.

The features of the artistic Kyiv tradition are still preserved in a number of icons of the 12th and early 13th centuries, originating mainly from Novgorod. This is the “Savior Not Made by Hands” (the face of Christ depicted on the board) from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin (XII century). This icon had special veneration in Novgorod and was a glorified image. This is evidenced by one of the Novgorod manuscripts of the 13th century (Zakharyevsky prologue). The stern face of Christ with huge eyes is painted in olive-yellow tones. Her restraint is enlivened by the red flush of her cheeks, as well as her forehead and the contour of her nose, her differently arched eyebrows give the face of Christ

Special expressiveness, just as asymmetry and curvature of lines endow Novgorod churches with special plastic expressiveness.

The main, central image of all ancient Russian art is the image of Jesus Christ, the Savior, as he was called in Rus'. Savior (Savior) - this word absolutely accurately expresses the idea of the Christian religion about him. It teaches that Jesus Christ is Man and at the same time God and the Son of God, who brought salvation to the human race.

Traditionally located on any image of him on both sides of the head IC XC - a word designation of his personality, an abbreviation of his name - Jesus Christ ("Christ" in Greek - the anointed one, the messenger of God). Also traditionally, the heads of the Savior are surrounded by a halo - a circle, most often golden - a symbolic image of the light emanating from it, the eternal light, which is why it takes on a round, beginningless shape. This halo, in memory of the sacrifice he made on the cross for people, is always lined with a cross.

A very important and widespread type of depiction of the Savior in ancient Russian art was the type called “Savior Almighty”. The concept of "Almighty" expresses the basic idea of Christian doctrine about Jesus Christ. “Savior Almighty” is a half-length image of Jesus Christ in his left hand with the Gospel - a sign of the teaching he brought to the world - and with right hand, the right hand raised in a gesture of blessing addressed to this world. But not only these important semantic attributes unite the images of the Almighty Savior. The artists who created them sought with particular completeness to endow the image of Jesus Christ with divine power and grandeur.

A mosaic image of the Savior Pantocrator has reached us in the dome of one of the oldest churches - the Hagia Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (1043-1046).

With the same attributes of the Lord of the world as the Savior Almighty, with the Gospel in his left hand and his right hand raised in blessing, Jesus Christ was also depicted in the popular compositions “The Savior on the Throne.” His royal power was indicated here by the very sitting on the throne (throne). In these images it was especially clear that the Lord of the world is also its judge, since “having sat on the throne,” the Savior will execute his final judgment over people and the world.

Luke, Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev, Alypiy Pechersky.

When was the first icon painted? Who was the first icon painter? What was the first icon? What material was it made of? There is no exact answer to all these questions, and most likely there never will be. There are only hypotheses that have come down to us from time immemorial, but they do not prove anything at all. It so happened that history considers the first creator of the icon to be Apostle Luke, who created the image of the Mother of God during the earthly life of Jesus Christ.

The word icon comes from ancient Hellas, it means the image of the one depicted on it. An icon is an image of a saint to whom a believer’s prayer is addressed, because the main purpose of an icon is to remind of prayer, to help accomplish it with soul and body, and to be a guide between the person praying and the image of the Saint. The spiritual eyes of a believer are so undeveloped that he can only contemplate the Heavenly world and those living in it with his physical eyes. Only after having traveled the spiritual path sufficiently can visions of the heavenly powers be revealed to his gaze. And in history there are many facts when the Saints themselves appeared to ascetics as if in reality.

Prayer is a frank conversation with the Lord, which always helps, but this help can come either immediately or after many years. But always and everywhere, prayer before the image on the icon helps the believer to understand finding the truth in the state of grace that he experiences during and after prayer. After sincere prayers, insight comes, and peace and harmony comes into a person’s life.

IN modern society Many consider icons to be luxury items; they are collected and exhibited for public viewing. But an icon is not just a beautiful and valuable thing. For a true Christian, it is a reflection of his inner world - the world of the soul. That is why, in everyday worries or in rage, one glance at the icon is enough to remember the Lord.

From the time of the emergence of Christianity to the present day, many believers have tried to create icons. For some, it worked out better, for others not so much, but all the time, humanity admires the beauty of various icons, their miraculous and healing power. In the history of mankind, in different time and in different centuries, masters of icon painting lived and worked, creating unique icons, spiritual images that are pearls of spiritual and historical heritage. This article talks about some famous icon painters from different countries world, about their enormous contribution to the history of icon painting, and accordingly to the spiritual heritage of people.

Evangelist and icon painter Luke (1st century)

Luke - according to legend, is the first to paint an icon. According to legend, it was an icon of the Mother of God, after which the icon painter created an icon of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul. The future evangelist and icon painter was born into a noble family of Greek pagans. Holy Scripture reports that Luke lived to a ripe old age. During the earthly life of Jesus Christ, he was in his close circle, was an eyewitness to the Lord’s death on the cross, and when Christ appeared to him on the way to the village of Emmaus, he was one of the first to witness the Holy Resurrection of the Lord. Luke's earthly life was full of travel, he walked a lot around the world, and everywhere he conveyed to people the word of God and the commandments of Christ. With the blessing of the Lord, he wrote the book “The Acts of the Holy Apostles.” It is believed that the icons of the Mother of God “Vladimir”, “Smolensk” and “Tikhvin” that have survived to this day belong to the brush of St. Luke, but on this moment there is no evidence of this, but only speculation and hypotheses, because in ancient times signs and signatures confirming authorship were not applied to icons. But regarding the “Vladimir” icon, there are other opinions of famous theologians and icon painting specialists. Firstly, the fact that this icon is the creation of the Evangelist Luke is stated in the Holy Scriptures, and secondly, on many ancient icons the Evangelist Luke is depicted painting the image of the Mother of God, which, according to experts, is very similar to the image of the Virgin Mary on the icon "Vladimir". This spiritual image is extraordinary, natural and unique, and also has miraculous properties. That is why the contribution to the work of icon painting of St. Luke cannot be expressed in words. His work is also priceless because it was the Apostle Luke who was the first to capture and preserve for all centuries the image of the Mother of God, so that descendants would pray to the spiritual image and receive help. The Holy Evangelist Luke is the patron saint of icon painters, so it was appropriate for him to begin creating a new icon.

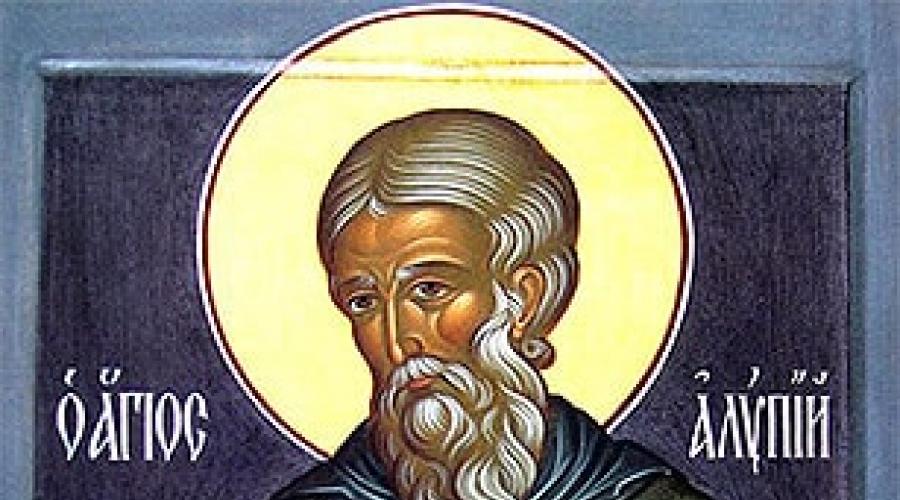

Alypiy of Pechersk (date of birth - unknown, date of presentation to the Lord - 1114)

At the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, the Monk Alypius of Pechersk lived and created his wonderful icons. He received his name from the name of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, where from a young age he led a monastic life in strict fasting and prayers. Venerable Alypius is rightly considered the first icon painter in Kievan Rus, his creative talent gave impetus to the development of icon painting in Orthodoxy. Alypius studied the craft of icon painting from masters from distant Greece, who at that time painted Pechersk Lavra. One day, the monk Alypius had a vision, so, during the painting of the Lavra, which he observed, the image of the Mother of God was clearly displayed on the altar of the temple. Alypius accepted this wondrous miracle as a sign for icon painting.

According to church tradition, icon painting was easy for the monk Alipius, the icons were created as if by themselves, but in order for them to be unique, Alipius spent a long time and diligently painting them. He created several icons of the Lord and Mother of God. The unique icon “Presta Tsarina” also belongs to the work of Alypius; it is currently located in the Assumption Church of the Moscow Kremlin, which already says a lot. What makes the work of St. Alypius of Pechersk unique and priceless? As it turned out, the icons that the saint created throughout his life have a miraculous and healing power. They do not age, the material from which they are made does not deteriorate, and besides, the images on the icons always remain distinct. During the time of the Bolsheviks, when churches were destroyed and burned, the icons created by Alypiy of Pechersk always remained unharmed. Many theologians believe that the icons have such uniqueness and miraculous power because when the Monk Alypius worked on them, he always read a prayer, which certainly speaks of the holiness of the master icon painter and his creations. Alypius of Pechersk's contribution to the history of icon painting is unique; his icons are found in many churches and monasteries throughout the world. Upon the repose of the Lord, he was canonized as a Saint, and after two centuries, an unknown artist created the icon “St. Alypius the Iconographer of Pechersk,” where the monk is depicted with a brush in his hands and an icon, confirming that he was and forever remained a skilled icon painter.

Theophanes the Greek (about 1340-1410)

One of the most famous and talented icon painters of the 14th century is certainly Theophanes the Greek. Born around 1340 in the Byzantine Empire. He traveled a lot and for a long time around the world, visited Constantinople, Caffa, Galata, Chalcedon, where he painted temples, and, as theologians say, monastic monasteries. It is believed that at this time Theophanes the Greek painted more than 40 churches, although there is no evidence of this; all the frescoes and paintings created by the great master, unfortunately, have not survived. Fame, glory and gratitude from his descendants came to the icon painter Feofan after his arrival in Russia. In 1370, he arrived in Novgorod, where he immediately began work in the Church of the Transfiguration. At this time, Theophanes the Greek did a huge job of painting the temple, which has survived to this day. The best survivors are the chest-length image of the Savior Pantocrator in the central dome, as well as the frescoes on the northwestern side of the temple. Anyone can see this unique painting and appreciate the artist’s talent. In addition, in Russia you can see the paintings of Theophanes the Greek in the churches of Moscow and other cities, where he depicted many Saints who are mentioned in Scripture.

Yet the main and unique work of Theophanes the Greek is rightfully considered to be the icons that he created throughout his life. The “Donskaya” icons of the Mother of God, “The Transfiguration of the Lord Jesus Christ on Mount Tabor”, to this day give joy to visitors to the Tretyakov Gallery, as they have been preserved there for many years. Feofan the Greek - made a huge contribution to the development of icon painting, both in Russia and in other countries, because his icons are fascinating, they are beautifully designed and are distinguished by warmth. The icons painted by Feofan are unique, as they were created in a special style, known only to the master who created them. The brushes of Theophanes the Greek are credited with creating the double-sided icon “Our Lady of the Don,” where the other side depicts the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The painting of the Church of the Archangel Michael in Pereyaslavl-Zalessky also belongs to the great Byzantine icon painter. Already in old age, he took an active part in painting the Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. Here he worked together with the great Russian artist - icon painter Andrei Rublev and a certain elder Prokhor, who, unfortunately, was known to few people as an icon painter. It is unknown where and when Theophanes the Greek died, presumably his soul went to the Lord - around 1410.

Andrei Rublev (about 1360 - 1430)

The life and work of the great Russian artist is a whole era, maybe even an era in the history of Russian icon painting, when morality and faith in high ideals were revived. Perhaps none of the Russian icon painters did as much as Andrei Rublev did in icon painting. His works show the greatness and depth of Russian icon painting, and also prove the revival of faith in man and the ability to self-sacrifice. Unfortunately, the real name of the icon painter is unknown; he was named Andrei Rublev after his tonsure, when the great future master became a monk. Most likely, the Lord spiritually blessed him to paint icons, because it was with his monastic name that he, Andrei Rublev, became known to the whole world. The icons of this master are extraordinary, they contain beauty and grandeur, expressiveness and splendor, brightness and mystery, grace and elegance, and, of course, healing and miraculous power, deep grace.

It makes no sense to list all the icons created by the master; everyone knows them, but it is worth noting the icons of the Nativity of Christ, the Meeting, the Raising of Lazarus and the Old Testament Trinity. These icons are extraordinary. They have sparkle, irresistible aesthetics and artistic charm. But Andrei Rublev is famous not only for icon painting. Together with the Byzantine master Theophan the Greek, the Russian icon painter painted churches and monastic monasteries. The frescoes created by the hands of Andrei Rublev are unique and differ from the frescoes of many other masters in the extraordinary and unique way they are applied. IN early XIX century, in the Zvenigorod Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, during restoration, three icons were found quite by accident - “Savior”; "Archangel Michael" and "Apostle Paul". After much research, experts came to the conclusion that they were written by Andrei Rublev. The style of writing and the harmony of colors became irrefutable proof of this. Quite accidentally, but deservedly, three more were added to the huge list of icons created by Andrei Rublev. Thank God, the icons painted by the monk icon painter Andrei Rublev have survived to this day, and delight us with their charm, harmony and their miraculous power, and this is not surprising, because according to church belief, angels helped Andrei Rublev create icons.

Creating an icon is not an easy task, and not everyone can do it. The great masters of icon painting created works that could touch the soul of everyone. The power of these masters is the power and grace of the Lord revealed in our world. To become a conductor of the Will and grace of the Lord, you need to be pure in thoughts and feelings. Spiritual exploits, deep constant internal struggle, humility, observance of the commandments and rules of the Church - these are the pillars on which a person’s righteousness is based. This righteousness allows us to convey His heavenly image and light in icons, without distorting or introducing something alien into them, without darkening or overshadowing it.

Eat famous case when Mother Matrona asked a certain icon painter to paint the icon “Recovery of the Dead.” He started it, and a lot of time passed before it was finally done. The icon painter was at times in despair and said that he could not complete it. However, according to Matrona’s instructions, he went to repent, and when it didn’t work out again, he went to repent again until he was completely cleansed. Only after this did his work bring results.

The works of modern icon painters are no less amazing and unique; they are known in all countries of the world. And despite the fact that in other countries different beliefs, the works of our icon painters are valued as works artistic arts, as standards of completeness, harmony, penetrating depth of knowledge, as the ability to convey the “indescribable” in their works.

Iconography. Russian icon.

Iconography- one of the recognized peaks of world art, the greatest spiritual heritage of our people. The interest in it is enormous, as are the difficulties of perceiving it for us.The Russian icon has constantly attracted and still attracts the closest attention of art critics, artists and simply art lovers with its unusualness and mystery. This is due to the fact that ancient Russian icon painting is a peculiar, unique phenomenon. It has great aesthetic and spiritual value. And, although a lot of specialized literature is currently being published, it is very difficult for an unprepared viewer to decipher the encoded meaning of the icon. To do this, some preparation is required.

We have icons in almost every house, but do residents know the history of the appearance of icons in the house, the meaning of colors, the names of icons, the history of the icon of the Mother of God?

It turns out that the first image of Christ, according to legend, appeared in the 6th century. It is called the Image Not Made by Hands, because. arose from the contact of fabric (towel, scarf) with the face of Christ. In legends of the 6th century. It is said that Abgar, the king of the city of Edessa, who was suffering from leprosy, sent his servant to Christ with a request either to come to Edessa and heal him, or to allow him to paint a portrait of Him. In response to this request, Christ washed His face, applied a towel to it, and the face was miraculously imprinted on the canvas. Having received the miraculous portrait of Christ, Abgar recovered, after which he attached it to a board and placed it above the city gates of Edessa. In 944 Miraculous Image was transferred to Constantinople. After the defeat of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204, the Image disappeared.

Main images Christian art There were images of Christ, they were depicted on the walls of churches and on icons. The most numerous types were the icons of the Mother of God.

Not every artist could paint icons. Not only a blessing is required over him, a special prayer is read over the artist, calling on God’s help in painting icons and spiritual paintings. When icons are painted, they are painted not with a cigarette in their teeth, but with a prayer on their lips. A person who wants to paint icons must be humble. On Athos, the monks painted icons with such humility and reverence that the icons immediately became miraculous even without consecration. Only those people who are an Orthodox Christian, who constantly goes to services, confesses, takes communion, and fasts, have the right to paint icons. You can only paint an icon while fasting! It is necessary for the icon painter to have a pure soul, and then the image on the icon will be pure. And if a person is dead in soul, then no matter how professional he is, he will paint a dead icon.

In the 16th-17th centuries, at the Stoglavy Cathedral (1551) and at the Councils of 1667-1674, the iconographic canon was approved. Russian “legalizations” strictly stipulated that only good people who believe in God should be allowed to paint icons. Icons by Andrei Rublev, Dionysius, and Simon Ushakov were taken as examples of the iconographic canon in Rus'.

Preparing the board for the icon.

The basis of any icon, as a rule, is a wooden board. In Russia, linden, maple, spruce, and pine were most often used for these purposes. The choice of wood type in different regions of the country was dictated by local conditions. Thus, in the north (Pskov, Yaroslavl) they used pine boards, in Siberia they used pine and larch boards, and Moscow icon painters used linden or imported cypress boards. Of course, it was preferable lime boards. Linden is a soft, easy-to-work wood. It does not have a pronounced structure, which reduces the risk of cracking of the board prepared for processing. The base of the icons was made of dry, seasoned wood. The individual parts of the board were glued together with wood glue. Knots found in the board were usually cut out, since the gesso cracked in these places when drying. Inserts were glued in place of the cut knots.

Until the second half of the 17th century, a small depression was chosen on the front of the board, which was called an “ark” or “trough,” and the ledge formed by the ark was called “husk.” Already from the second half of the 17th century, boards, as a rule, were made without an ark, with flat surface, but at the same time the fields framing the image began to be painted over with some color. In the 17th century, the icon also lost its colored fields. They began to be inserted into metal frames, and in iconostases they were framed with a frame in the Baroque style.

To prepare the board for the ground ("gesso"), craftsmen used animal glue, gelatin or fish glue. The best fish glue was obtained from the bladders of cartilaginous fish: beluga, sturgeon and sterlet. Good fish glue has great astringent strength and elasticity.

A layer of fabric (pavolok) was glued onto a carefully processed and glued board. For these purposes, fabric made from flax and hemp fiber, as well as a durable type of gauze, was used. To prepare the fabric for gluing, it was first soaked in cold water, then boiled in boiling water. Pavolok, pre-impregnated with glue, was applied to the glued surface of the board. Then, after thoroughly drying the pavolok, they began to apply gesso.

SOILS, THEIR COMPOSITION AND PROPERTIES

It is known that even 4 thousand years BC. e. The ancient Egyptians, trying to provide the dead pharaohs and their entourage with life in the afterlife, embalmed the body and placed it in a wooden sarcophagus covered with cloth. The sarcophagus was primed with a composition similar to gesso and the face of the deceased was painted with tempera paints. Obviously, the skill and tradition of applying gesso to wood came from there.

Gesso was prepared from well-sifted chalk mixed with fish glue. Although gypsum, alabaster, and whitewash were sometimes used to make gesso, chalk in this case is preferable, since it gives a very quality soil, characterized by whiteness and strength.

Nowadays, restoration workshops use soil, the preparation of which begins with heating fish glue to a temperature of 60°C and adding small portions of finely ground dry chalk to it. The composition is thoroughly mixed with a metal spatula. Do not add to the resulting composition a large number of polymerized linseed oil or oil-resin varnish (a few drops per 100 ml of mass).

To apply soil to the board, a wooden or bone spatula was used - a “spatula”, as well as bristle brushes. Gesso was applied to the board thin layer. Each layer was thoroughly dried. Sometimes craftsmen applied up to 10 layers.

The layers of primer were applied very thinly; the thinner, the lower the risk of cracking. After final drying, the soil was leveled with various blades and smoothed with pumice, sawn into flat pieces. Polished the surface of gesso with stems horsetail, which contains a large amount of silicon, allowing it to be used as a polishing material.

TO end of XVII and at the beginning of the 18th century they began to lay the soil directly on the board. This was due to the fact that tempera began to be replaced with oil paints and oil and drying oil were added to the soil. Sometimes gesso was prepared with egg yolk, glue and a lot of butter. This is how the base prepared for painting was obtained.

THE DIFFERENCE OF AN ORTHODOX FROM A CATHOLIC ICON

Experts in art history and religion find the difference between Orthodox icons and Catholic icons in the same difference that exists between icon painting and painting. The icon painting traditions of Catholics and Orthodox Christians have a huge gap; they developed independently over several centuries, so it is not difficult to distinguish icons from each other.

The school of Orthodox icon painting is based on the Byzantine tradition, which professes strict monumentality, smoothness and slowness of movements. Her icons are full of triumph and heavenly joy; they serve for prayer. This is an image behind which there is always a Prototype - God.

Catholic icons are not an image, but a picture, an illustration on a religious, biblical theme. It is very picturesque and often has an instructive and edifying character. The Orthodox icon does not teach or tell about anything, only pointing to another world; from it the believer himself draws a meaning that is understandable and visible only to him. Therefore, such an icon always requires decoding. Its writing is subject to a strict canon that does not allow deviations in color or method of depicting individuals.

Another difference is the perspective: on a Catholic icon it is straight, but on an Orthodox icon it is reversed.

LIGHTING ICONS

Nowadays, according to tradition, icons, after being painted or made, are consecrated in the temple. The priest reads special prayers and sprinkles the image with holy water. An icon is holy because it depicts the Lord, the Mother of God or saints.

For many centuries, there was no special rite for the consecration of icons. The icon was created in the Church, was inseparable from the Church and was recognized as holy by its compliance with the iconographic canon, that is, a set of rules according to which the authenticity of a sacred image is determined. Since ancient times, an icon has been recognized as a holy image due to the inscription on the icon of the name of the person depicted.

The modern rite of consecration of icons arose in the era of impoverishment of Orthodox icon painting, during the period of borrowings from secular and Western painting that were introduced into Orthodox icons. At this time, to confirm the holiness of what was depicted, icons began to be consecrated. Actually, this rank can be understood as a testimony from the Church about the authenticity of the icon, that the one depicted is the one who is inscribed.

Nowadays, embroidered icons are often brought to be blessed, but those who decide to take this seriously need to talk to the priest and take a blessing for the upcoming lesson, and inquire about the icon painting canons. Creating icons is serious work that requires spiritual preparation. You can't treat it as an exciting hobby.

For a believer in medieval Rus', there was never a question whether he liked an icon or not, how or how artistically it was made. Its content was important to him. At that time, many did not know how to read, but the language of symbols was instilled in any believer from childhood.

Symbolism of color, gestures, depicted objects- this is the language of the icon, without knowing which it is difficult to assess the meaning of icons.

Clothing on icons is not a means to cover bodily nudity, clothing is a symbol. She is a fabric from the deeds of a saint. Interesting information about the nature of the clothes and vestments in which the characters of the icons dress. Each image has clothes that are characteristic and unique to it. One of important details– folds. The nature of the arrangement of folds on the clothes of the saints indicates the time of painting of the icon. In VIII – XIV centuries folds were drawn frequent and small. They talk about strong spiritual experiences and a lack of spiritual peace. In the 15th – 16th centuries, folds were drawn straight, long, and sparse. All the elasticity of spiritual energy seems to break through them. They convey the fullness of ordered spiritual forces.

Around the head of the Savior, the Mother of God and the holy saints of God, the icons depict a radiance in the shape of a circle, which is called a halo.

A halo is an image of the radiance of light and Divine glory, which transforms a person who has united with God.

There are no shadows on the icons.

Each item in the icon is a symbol:

SYMBOLICS OF GESTURES

Hand pressed to the chest - heartfelt empathy.

A hand raised up is a call to repentance.

A hand extended forward with an open palm is a sign of obedience and submission.

Two hands raised up - a prayer for peace.

Hands raised forward - a prayer for help, a gesture of request.

Hands pressed to the cheeks are a sign of sadness, grief.

COLOR IN ICON:

Golden joy is proclaimed in the icon with color and light. Gold (assist) on the icon symbolizes Divine energy and grace, the beauty of the other world, God himself. Solar gold, as it were, absorbs the evil of the world and defeats it.Yellow, or ocher– the color closest in spectrum to gold, often just a substitute for it, is also the color of the highest power of angels.

Purple or crimson, color was a very significant symbol in Byzantine culture. This is the color of the king, the ruler - God in heaven, emperor on earth. Only the emperor could sign decrees in purple ink and sit on a purple throne, only he wore purple clothes and boots (this was strictly forbidden to everyone). Leather or wooden bindings of the Gospels in churches were covered with purple cloth. This color was present in the icons on the robes of the Mother of God, the Queen of Heaven.

Red– one of the most noticeable colors in the icon. This is the color of warmth, love, life, life-giving energy. But at the same time, it is the color of blood and torment, the color of Christ’s sacrifice. Martyrs were depicted in red robes on icons.

White color - a symbol of Divine light. It is the color of purity, holiness and simplicity. On icons and frescoes, saints and righteous people were usually depicted in white. The righteous are people who are kind and honest, living “in truth.”

Blue and cyan colors meant the infinity of the sky, a symbol of another, eternal world. Blue color was considered the color of the Mother of God, who united both earthly and heavenly. The paintings in many churches dedicated to the Mother of God are filled with heavenly blue.

Green color– natural, living. This is the color of grass and leaves, youth, blossoming, hope, eternal renewal. The earth was painted with green; it was present where life began - in the scenes of the Nativity.

Brown is the color of bare earth, dust, everything temporary and perishable.

Gray is a color that has never been used in icon painting. Having mixed black and white, evil and good, it became the color of obscurity, emptiness, and nothingness. This color had no place in the radiant world of the icon.

Black color– the color of evil and death. In icon painting, caves—symbols of the grave—and the yawning abyss of hell were painted black. In some stories it could be the color of mystery. Black robes of monks who left ordinary life, is a symbol of abandonment of previous pleasures and habits, a kind of death during life.

The basis of color symbolism Orthodox icon, like all church art, is the image of the Savior and the Mother of God.

The image of the Blessed Virgin Mary is characterized by dark cherry omophorion- a robe worn on the shoulders and a blue or dark blue chiton. Chiton- the Greek name for lower clothing, dresses, clothing in general among ancient peoples.

The image of the Savior is characterized by a dark brown-red chiton and a dark blue himation(cloak, cape). And here, of course, there is a certain symbolism: blue is the Celestial color (symbol of Heaven).

The Savior's blue himation is a symbol of His Divinity, and the dark red tunic is a symbol of His human nature.

Dark red the color of the Virgin's clothes is a symbol of the Mother of God.

The saints on all icons are depicted in white or somewhat bluish vestments.

Iconography is the painting of icons, a type of painting common in the Middle Ages, dedicated to religious subjects and themes.

An icon as an object of religious worship is an indispensable accessory for everyone Orthodox church. In Ancient Rus', for example, there was a cult of icons as sacred objects. They were worshiped, many legends were told about them, superstitious people believed that the icons were endowed with mysterious powers. They were expected to perform miracles, deliverance from diseases, and help in defeating the enemy. The icon was a mandatory part of not only church decoration, but also of every residential building. At the same time, the artistic quality of the icons was sometimes given secondary importance.

Nowadays, we value only those icons that are works of art; we perceive them as monuments of the past, recognizing their high aesthetic value.

Miracle of George about the serpent. XVI century Moscow school. State Tretyakov Gallery. Moscow.

The oldest monuments of icon painting date back to the 6th century. Large collections of them are concentrated in monasteries in Sinai (Sinai Peninsula), Mount Athos (Greece) and Jerusalem. Icon painting arose on the basis of the traditions of late Hellenistic art. The initial works - “portraits” of saints - were made using the technique of mosaic, encaustic, then the icons were painted in tempera, from the 18th century. - oil paints on wooden boards, less often - on metal ones.

In the X-XII centuries. Byzantium became the center of icon painting (see Byzantine art). At the beginning of the 12th century. a famous masterpiece was created - the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir, which is still kept in the Tretyakov Gallery. The Byzantine style had a great influence on the painting of Western Europe, Ancient Rus', South Slavic countries, Georgia, which was associated with the spread of Christianity.

The heyday of ancient Russian painting occurred at the end of the 14th - mid-16th centuries. What is this period of our history like? Having gone through the trials of the Mongol-Tatar yoke, the Russian people began to unite to fight the enemy and realize their unity. In art he embodied his aspirations and aspirations, social, moral, and religious ideals. Among the icons of this time, the remarkable works of Theophanes the Greek stand out. His art, passionate, dramatic, wise, stern, sometimes tragically intense, made a strong impression on Russian masters.

The era was reflected in its own way in the work of Andrei Rublev and his students. In the works of Andrei Rublev, the dream of his contemporaries about a moral ideal was embodied with extraordinary artistic power; his images affirm the ideas of goodness, compassion, harmony, joy, which answered the people's aspirations.

Along with the Moscow school in the XIV-XV centuries. Icon painting flourishes in Novgorod, Pskov, Tver, Suzdal and other cities.

At the end of the 15th century. A new star appears on the Moscow skyline - master Dionysius. Dionysius had a great influence on his contemporaries. For the entire first half of the 16th century. reflections of the poetry of his colors fall.

Dionysius. Metropolitan Alexy heals Taidula (the khan's wife). Mark from the icon “Metropolitan Alexy in the Life”. Beginning of the 16th century Wood, tempera. State Tretyakov Gallery. Moscow.

A turn in the development of icon painting occurred in the middle of the 16th century, when church control over the work of icon painters sharply increased. The decisions of the Stoglavy Council referred to Andrei Rublev as a model, but essentially cut off the precious thread coming from him.

A historical examination of icon painting helps to understand its essence. Icon painters usually did not invent or compose their own stories like painters. They followed the iconographic type developed and approved by custom and church authorities. This explains why icons on the same subject, even separated by centuries, are so similar to each other. It was believed that masters were obliged to follow the models collected in iconographic originals and could only express themselves in color. Otherwise they were at the mercy of traditional canons. But even within the framework of constant gospel stories, with all the respect for tradition, the masters always managed to add something of their own, enrich, and rethink the ancient model.

Until the 17th century painters usually did not sign their works. Chronicles and others literary sources mention the most revered icon painters: Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev, Daniil Cherny, Dionysius. Of course, there were much more talented craftsmen, but their names remained unknown to us.

Modern people cannot help but be surprised by the sharp contradictions between the cruelty and rudeness of the morals of feudal Rus' and the nobility and sublimity of ancient Russian art. This does not mean that it turned away from the drama of life. The Russian people of that era delved into the course of life, but sought to put into art what they really lacked and what the aspirations of the people attracted them to.

For example, the images of the martyrs Boris and Gleb then looked like an exhortation to the princes to abandon civil strife. The icon “Battle of the Novgorodians with the Suzdalians” showed the local patriotism of those years when the Novgorodian freedom began to be threatened by the regiments of the Moscow princes.

Old Russian masters were deeply convinced that art makes it possible to touch the mysteries of existence, the mysteries of the universe. The hierarchical ladder, pyramidality, integrity, subordination of parts - this is what was recognized as the basis of the world order, which was seen as a means of overcoming chaos and darkness.

This idea found expression in the structure of each icon. The Christian temple was thought of as a semblance of the world, the cosmos, and the dome - the firmament. Accordingly, almost every icon was understood as a semblance of a temple and at the same time as a model of the cosmos. Modern man does not accept the ancient Russian cosmos. But he, too, cannot help but be captivated by the fruits of poetic creativity generated by this view: a bright cosmic order triumphing over the forces of dark chaos.

Old Russian icon painting paid great attention to images of gospel scenes from the life of Christ, the Mother of God (Virgin Mary) and saints. Among the many different motives, she chose the most constant, stable, and universally significant.

George the warrior. Icon of the 12th century. State museums of the Moscow Kremlin.

Particular attention should be paid to a group of such icons in which folk ideals were manifested, and agricultural Rus' had its say. These are primarily icons dedicated to Florus and Laurus, patrons of cattle, George, Blasius and Elijah the Prophet, who was depicted on a bright, fiery background as a successor pagan god thunder and lightning of Perun.

Among the subjects and motifs that especially appealed to the people of Ancient Rus', one should mention the Rublev type of “Trinity”: three figures, full of friendly disposition, forming a closed group. Andrei Rublev expressed this state with the greatest clarity and captivating grace. Rehashes of his compositions and free variations on this theme are constantly found in Russian icons.

In the world of ancient Russian icons, the human element is of great importance. The main subject of icon painting is a deity, but it appears in the image of a beautiful, exalted person. The deep humanism of the Russian icon also lies in the fact that everything depicted passed through the crucible of a responsive human soul and was colored by its empathy. In his impulse towards the lofty, a person does not lose the ability to look tenderly at the world, to admire the frisky running of horses, the shepherdesses with their sheep - in a word, all the “earthly creatures,” as they used to say then.

Icon painting is symbolic art. It is based on the idea that everything in the world is just a shell, behind which a higher meaning is hidden, like a core. Piece of art hence it acquires several meanings, which makes the icon difficult to perceive. Both the plot and the artistic form are symbolic here. Each icon, in addition to the fact that it depicts a legendary event or character, also has a subtext in which its true content is revealed.

Icons in their content are addressed not to one person, but to a community of people. They formed a row in the temple - an iconostasis, benefiting from their proximity to each other. The Old Russian iconostasis represented an integral, harmonious unity. The first large iconostases with human-sized figures date back to the beginning of the 15th century, and since then not a single temple could do without such a majestic structure. Its literal meaning is the prayer of the saints addressed to Christ, the Almighty, seated on the throne (Deesis rank - row). But since there was also a local row with icons on various topics, and a festive one - with scenes from the life of Christ and Mary, and a prophetic one (images of the apostles, prophets), the iconostasis acquired the meaning of a kind of church encyclopedia. At the same time, the iconostasis is a remarkable artistic creation of ancient Russian culture. Its significance in the development of ancient Russian icons is difficult to overestimate. Many icons cannot be explained and understood outside the combination in which they were located in the iconostasis.

Icon painting has developed the highest artistic skill, a special understanding of drawing, composition, space, color and light.

The drawing conveyed the outlines of objects so that they could be recognized. But the purpose of the drawing was not limited to identification. Graphic metaphor - the poetic likening of a person to a mountain, a tower, a tree, a flower, a slender vase - is a common phenomenon in Russian icon painting.

Composition is a particularly strong point of Old Russian icons. Almost every icon was thought of as a semblance of the world, and accordingly, a middle axis is always present in the composition. At the top there is the sky (the highest tiers of existence), and at the bottom the earth (“heaven”) is usually designated, sometimes the underworld is below it. This fundamental structure of the icon, regardless of the plot, influenced its entire composition.

Ancient texts list the favorite colors of our icon painters: ocher, cinnabar, cormorant, gaff, cabbage roll, emerald. But in reality, the range of colors of ancient Russian painting is more extensive. Along with pure, open colors, there were many intermediate ones. They vary in aperture and saturation; among them there are sometimes nameless shades that cannot be described in words; only the human eye can catch them. The colors glow, shine, ring, sing and all this brings great joy. Sometimes, with just one color, for example, a red cloak fluttering in the wind in the icon “George’s Miracle on the Dragon,” a warrior is given a deep characterization.

Old Russian icon painting is one of the largest phenomena in world art, a unique, unique phenomenon of enormous artistic value. She is born historical conditions development of our country. But the values it creates are public property. For us, ancient Russian icon painting is of great value, in particular because many of its artistic features were used in a reinterpreted form by major contemporary artists (for example, K. S. Petrov-Vodkin, V. A. Favorsky, P. D. Korin, etc. .).

In our country, the business of collecting and disclosing works of ancient Russian icon painting has acquired national proportions. Lenin's decrees on the nationalization of art monuments (see Protection of historical and cultural monuments in the USSR) laid the foundation for the creation of the largest repositories of ancient Russian painting in the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum.

In the year of the 600th anniversary of the birth of Andrei Rublev, the Museum of Ancient Russian Art named after him was opened in the former Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.