We have logical errors. Logical errors. III. What are the causes of logical errors?

Read also

Logical errors. How they prevent you from thinking correctly Uemov Avenir

B. How to avoid logical errors in thoughts of various forms

1. What laws of thinking are the rules of logical forms based on?

We got acquainted with logical forms of thinking. Now we can find out what rules must be followed in each of these forms of thought in order to think correctly and avoid logical errors in reasoning.

Just as in geometry there are different theorems that apply to different geometric forms, so in logic there are different rules of thinking that apply to different logical forms. Geometric theorems, whether they concern a triangle, a square, a cube or a trapezoid or any other geometric shape, are based on certain general principles - axioms. Also in logic there are a number of such initial general provisions, axioms, with the help of which individual rules of thinking are justified. These principles must be observed in every correct thought. Therefore, they are called the laws of correct thinking, or more often simply the laws of thinking.

First of all, every correct thought must be definite. This means that if the subject of a person’s thought or reasoning is, for example, the sea, then he should think about the sea, and not about anything else instead. You cannot replace one object of thought with another, as often happens with those who do not know how to think definitely and in the process of reasoning, without noticing it, replace one object with another, thinking at the same time that they are reasoning about the same thing.

The requirement of certainty can be formulated in the form of the proposition “every thought must be identical to itself.” This law of identity. Its formula: A = A.

Popular wisdom warns against violating the law of identity. “One about Thomas, the other about Yerema” - they say about those who, talking about different things, believe that they are talking about the same thing.

On the other hand, no thought can be identical to something that denies it. This position is called law of contradiction, expressed as the formula “ A don't eat no A».

The law of contradiction prohibits contradictions. Based on the law, contradictions must be rejected as absolutely incorrect, such as, for example, thoughts:

“liquid is a solid”;

"a point is a line."

What can the thought that interests us be equated to?

This is determined by the following law of thinking: “Every thought is either identical to a given thought or different from it” - “ B is or A, Or no A", where "or" is understood in a strictly divisive sense. For example, the concept “storm” either coincides with the concept “storm” or does not coincide. There is no third possibility here and cannot be. That's why this law is called law of excluded middle.

We can consider a given thought to be true if it is based on thoughts whose truth is already known. For example, the truth of the thought “dolphins breathe with their lungs” is justified by the truth of the thoughts “mammals breathe with their lungs” and “a dolphin is a mammal.”

The requirement that a particular thought be considered true only after reasons for this have been given is called law of sufficient reason.

This law also applies to the correctness of thought. A thought can be considered correct only if there are appropriate grounds for it.

These four laws: identity, contradiction, excluded third and sufficient reason - are general laws of correct thinking, applicable to all thoughts, different in form and content. But these laws, when applied to thoughts of different forms, manifest themselves differently.

Every logical error relates to one or another specific type of thought. Thoughts, as we have found out, differ in their logical form. Therefore, naturally, errors differ according to what logical form they belong to.

Logical errors can be divided into four groups, corresponding to the four logical forms of thought:

1) errors related to the concept;

2) errors in judgment;

3) errors in conclusions;

4) errors in evidence.

From the book Reflections by Absheroni AliABOUT THOUGHTS The vanity of our consciousness stems from the ordinariness of aspirations caused by a misunderstanding of the sublime meaning of life. Only lofty thoughts are worthy of reflection. To think means to suffer, and not to think means not to live. A thought and an arrow fly differently,

From the book Logical Fallacies. How they prevent you from thinking correctly by Uemov AvenirI. What is the essence of logical errors? At the entrance exams in mathematics at Moscow universities, many applicants were asked the question: “The sides of the triangle are 3, 4 and 5, what kind of triangle is this?” This question is not difficult to answer - of course, the triangle will be right-angled. But

From the book Stratagems. About the Chinese art of living and surviving. TT. 12 author von Senger HarroII. What is the harm of logical errors? In practical life, we are primarily interested in the question of how to find out whether a particular thought is true or false. In some cases, this can be established immediately, with the help of our senses - vision, hearing, touch, etc. In this way

From the book Selected Works author Shchedrovitsky Georgy PetrovichIII. What are the causes of logical errors? Why do people make logical errors? What is the reason that in some cases, for example, in the reasoning “2 + 2 = 4, the Earth rotates around the Sun, therefore, the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea,” the logical error is clear to everyone

From the book Clear Words author Ozornin ProkhorIV. The importance of practice and various sciences for eliminating logical errors Of course, the discussion above was not about the absolute inability to reason correctly. If a person could not reason at all, he would be doomed to death. People face the need to reason

From the book The Meaning of Life author Papayani Fedor2. How to avoid logical errors in concepts Medieval philosophers, who were called scholastics, persistently puzzled over the question: “Can God create a stone that he himself cannot lift?” On the one hand, God, as an omnipotent being, can do everything that

From the author's book3. How to avoid logical errors in judgments As already mentioned, a judgment can be considered as an expression of the relationship between concepts. If the relation of concepts expressed by a judgment corresponds to the relations of things, then such a judgment is true. If such a correspondence

From the author's book4. How to avoid logical errors in inferences First of all, let us dwell on inferences that come down to the transformation of premises, that is, on deductive inferences. The simplest among them, as we know, are direct inferences. No matter how simple

From the author's book5. How to avoid logical errors in evidence Incorrect conclusions are always associated, as we have seen, with an incorrect transition from one judgment to another, from premises to conclusions. To avoid errors in conclusions, you just need to follow all the rules of this

Avenir Uemov

Logical errors.

How they prevent you from thinking correctly

I. What is the essence of logical errors?

At the entrance exams in mathematics at Moscow universities, many applicants were asked the question: “The sides of the triangle are 3, 4 and 5, what kind of triangle is this?” This question is not difficult to answer - of course, the triangle will be right-angled. But why? Many examinees reasoned this way. From the Pythagorean theorem we know that in any right triangle, the square of one side - the hypotenuse - is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides - the legs. And here we just have 52 = 32 + 42. This means that from the Pythagorean theorem it follows that this triangle is right-angled. From the point of view of ordinary, so-called “common” sense, such reasoning seems convincing. But the examiners rejected it because it contained a gross logical error. Knowledge of the theorems alone was not enough to successfully pass the exam. The examinee should not have violated the rigor of reasoning required in mathematics.

Failure associated with this kind of error can befall a person not only in the mathematics exam.

A student entering the institute writes an essay on literature on the topic “Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace” - the heroic epic of the struggle of the Russian people.” He outlines a plan that goes like this:

1. Introduction. Historical significance of the novel.

2. Presentation:

a) war in the novel,

b) people of war,

c) partisan movement.

3. Conclusion.

No matter how well the applicant knows this material, no matter what he writes in his essay, already in advance, only on the basis of familiarity with the plan can one say that his work as a whole will be considered unsatisfactory. And this will be the result of a logical error made in the plan.

In the tenth grade of one of the Moscow schools, students were asked to answer in writing the question whether they should study geography. Among the many varied answers, one of the most typical was the following:

“The study of geography is necessary in order to give us the opportunity to learn, through the study of physical geography, about the surface, climate, vegetation of places where we have not been and, perhaps, never will be. And from economic geography we learn about the economy, industry, and political system of a given country. Without geography, we wouldn’t be able to travel around the country.” This answer also contains a serious logical error.

All the examples given here are taken, as we see, from completely different areas of knowledge. However, in all three examples the errors are of the same nature. They are called logical.

What is the essence of these errors?

If a person looking at the railway tracks going into the distance seems to be converging on the horizon at one point, then he is mistaken. The one who thinks that the fall of one grain to the ground does not make the slightest noise, that a piece of fluff has no weight, etc. is mistaken. Can these errors be called logical? No. They are associated with deception of vision, hearing, etc., these are errors of sensory perception. Logical errors relate to thoughts. You can also think about objects that you cannot see, hear, or touch at the moment, that is, you do not perceive sensually. We may think that the Earth revolves around the Sun, although we do not directly experience it. At the same time, our thoughts can correspond to reality, that is, be true, and they can contradict the real situation of things, that is, they can be erroneous, untrue.

Errors related to thoughts are also not always logical. A child can say that two and two are three. During an exam, a student may incorrectly name the date of an event. Both of them make a mistake in this case. If the reason for these errors is only poor memory, for example, a child does not remember the multiplication table, or a student has poorly learned chronology and forgot the required date, then the errors they made cannot be classified as logical.

Logical errors do not relate to thoughts as such, but to the way one thought is connected to another, to the relationships between different thoughts. Each thought can be considered on its own without connection with other thoughts. If such a thought does not correspond to the real state of affairs, then in this case there will be a factual error. The child and the student made exactly this kind of mistake. However, each thought can be considered in relation to other thoughts. Let’s imagine that a student who has forgotten the date of some event will not answer at random (“maybe I’ll guess!”), but will try, before answering the question, to mentally connect this event with some other facts known to him. He will establish in his mind a certain relationship between the thought of a given event and the thoughts of those facts with which he wants to connect this event. These kinds of connections between thoughts are constantly being established. The idea that a dolphin breathes with its lungs is associated with the idea that a dolphin is a mammal, and all mammals breathe with their lungs. Knowledge about the force of gravity gives people the confidence that a stone cannot, on its own, without any outside influence, lift off the ground and fly into the air. In our example, if the student’s thought about the facts with which he wants to connect this event corresponds to reality and he establishes the connection between his thoughts correctly, then, even forgetting the chronology, the student can give the correct answer to the question posed. However, if in the process of his reasoning he establishes a connection between the thought about a given event and thoughts about these facts that does not actually exist, then, despite knowing these facts, he will give the wrong answer. An error in the answer will be the result of an error in reasoning, which will no longer be a factual error, but a logical one.

We said that the connection between thoughts that a person establishes may or may not correspond to the connection between them that actually exists. But what does “really” mean? After all, thoughts do not exist outside a person’s head, and they can communicate with each other only in a person’s head.

Of course, there is absolutely no doubt that thoughts are connected with each other in a person’s head in different ways, depending on the state of the psyche, on the will and desires. One person associates pleasant thoughts about skating and skiing with the thought of the approaching winter. For another, the same thought evokes completely different, perhaps less pleasant thoughts. All such connections between thoughts are subjective, that is, depending on the psyche of each individual person. It will also depend on the mental characteristics of different people whether a person will establish a connection between the thought of a lake freezing in winter and the thoughts that in winter the temperature drops below zero and water freezes at this temperature. However, regardless of whether a person thinks about it or not, whether he connects or does not connect these circumstances with each other, whether it is pleasant or unpleasant for him, from the truth of the thoughts that water freezes at temperatures below zero and in winter the temperature is below zero, inevitably, objectively, completely independent of subjective tastes and desires, the truth of the idea that the lake freezes in winter follows.

Whether a thought arises in a person’s head or not, what kind of thought arises, how it connects with other thoughts - all this depends on the person. But the truth and falsity of thoughts do not depend on it. The proposition “twice two equals four” is true regardless of any characteristics of the psyche and structure of the brain of different people. It is also objectively true that “The Earth revolves around the Sun”, “The Volga flows into the Caspian Sea”, and it is objectively false that “The Earth is larger than the Sun”. But if the truth and falsity of thoughts do not depend on a person, then, naturally, there must be relations between the truth and falsity of various thoughts, independent of the will and desire of people. We saw such relationships in the examples above. The existence of these objective connections in thoughts is explained by the fact that thoughts and relationships between them reflect objects and phenomena of the world around us. Since objects and connections between them exist objectively, independently of a person, the connections between thoughts reflecting objects and phenomena of the external world must be objective and independent of a person. Therefore, recognizing as true the thoughts “a dolphin is a mammal” and “mammals breathe with their lungs,” we will have to recognize as true the thought that “a dolphin breathes with their lungs.” The truth of the last thought is objectively related to the truth of the two previous ones.

At the same time, such a connection does not exist between such three thoughts as “2 + 2 = 4”, “The Earth revolves around the Sun” and “Ivanov is a good student”. The truth of each of these propositions is not determined by the truth of the other two: the first two may be true, but the third may be false.

LOGICAL ERRORS– errors associated with violation of the logical correctness of reasoning. They consist in asserting the truth of false judgments (or the falsity of true judgments), or logically incorrect reasoning is considered correct (or logically correct reasoning is considered incorrect), or unproven judgments are accepted as proven (or proven ones as unproven), or, finally , the meaningfulness of expressions is incorrectly assessed (meaningless expressions are taken as meaningful, or meaningful ones are taken as meaningless). These aspects of cognitive errors can be combined with each other in various ways (for example, accepting a meaningless judgment as meaningful is usually associated with a belief in its truth). Logical errors were already studied by Aristotle in op. "Refutation of Sophistical Arguments." On this basis, in traditional logic, starting with the works of the scholastics, a detailed description of logical errors was developed. In accordance with the parts of proof distinguished in traditional logic, logical errors were divided into errors in relation to (1) the grounds of the proof (premises), (2) the thesis and (3) the form of reasoning (demonstration, or argumentation).

Errors of type (1) include, first of all, the error of a false basis, when a false proposition is accepted as a premise of evidence (this error is also called the fundamental fallacy, its Latin name is error fundamentalis). Since from false judgments, according to the laws and rules of logic, in some cases false and in others true consequences can be deduced, the presence of a false judgment among the premises leaves open the question of the truth of the thesis being proven. A special case of this error is the use (as a premise of proof) of a certain judgment that requires certain restrictive conditions for its truth, in which this judgment is considered without regard to these conditions, which leads to a certain falsity. Another case of the same error is that instead of some true premise necessary for a given proof, a stronger judgment is taken, which, however, is false (judgment A is said to be stronger than judgment B if from A, assuming its truth, B follows, but not the other way around).

A very common type of logical error of type (1) is the error of unproven reason; it consists in the fact that an unproven proposition is used as a premise, due to which the thesis of the proof also turns out to be unproven. Errors of this type include the so-called anticipation of the basis or “predecision of the basis” (Latin name - petitio principi), the essence of which is that a judgment is taken as the basis of the proof, the truth of which presupposes the truth of the thesis. An important special case of petitio principi is the circle in the proof. In traditional logic, all logical errors are divided into unintentional - paralogisms and intentional - sophistry .

The teaching of traditional logic about logical errors covers all main types of logical defects in people's meaningful reasoning. The means of modern formal logic only allow us to clarify the characteristics of many of them. In connection with the development of mathematical logic, the concept of a logical error naturally extends to cases of errors associated with the construction and use of the calculus considered in it; in particular, any error in the application of the rules for the formation or transformation of calculus expressions can be considered as logical. The source of errors in thinking are various reasons of a psychological, linguistic, logical-epistemological and other nature. The emergence of logical errors is facilitated primarily by the fact that many logically incorrect reasoning is outwardly similar to correct reasoning. An important role is also played by the fact that in ordinary reasoning, not all of its steps - the judgments and conclusions included in them - are usually expressed in explicit form. The abbreviated nature of the reasoning often masks false premises or incorrect logical techniques implicit in it. An important source of logical errors is insufficient logical culture, confusion of thinking, unclear understanding of what is given and what needs to be proven in the course of reasoning, and unclear concepts and judgments used in it. Confusion of thinking can be closely related to the logical imperfection of linguistic means used in the formulation of certain judgments and conclusions. The source of logical errors can also be emotional imbalance or agitation. The breeding ground for logical errors, especially for the error of false foundation, are certain prejudices and superstitions, preconceived opinions and false theories.

In the fight against logical errors, the use of logic is of no small importance. These means give the desired result in those areas where the factual material allows for the clarification of the form of reasoning prescribed by formal logic, the identification of omitted links of evidence, a detailed verbal expression of conclusions, and a clear definition of concepts. In these areas, the use of logic is an effective means of eliminating confusion, inconsistency and lack of evidence in thinking. Further development of the means of logic - already within the framework of mathematical logic - led to the formulation of a strict theory of deductive inference, to the logical formalization of entire branches of science, to the development of artificial (for example, the so-called information-logical) languages. At the same time, it turned out that the more complex the area of research, the more pronounced the inevitable limitations of formal logical means are. The means of logic by themselves, as a rule, do not guarantee the correctness of solving scientific and practical issues; Despite all their necessity, they give the desired effect only in the complex of all practical and cognitive activities of mankind.

Literature:

1. Asmus V.F. The doctrine of logic about proof and refutation. M., 1954, ch. 6;

2. Uemov A.I. Logical errors. How they prevent you from thinking correctly. M., 1958.

B.V. Biryukov, V.L. Vasyukov

Current page: 1 (book has 9 pages in total)

Avenir Uemov

Logical errors.

How they prevent you from thinking correctly

I. What is the essence of logical errors?

At the entrance exams in mathematics at Moscow universities, many applicants were asked the question: “The sides of the triangle are 3, 4 and 5, what kind of triangle is this?” 1

P. S. Modenov, Collection of competitive problems in mathematics with error analysis, ed. "Soviet Science", 1950, p. 113.

This question is not difficult to answer - of course, the triangle will be right-angled. But why? Many examinees reasoned this way. From the Pythagorean theorem we know that in any right triangle, the square of one side - the hypotenuse - is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides - the legs. And here we just have 5 2 = 3 2 + 4 2. This means that from the Pythagorean theorem it follows that this triangle is right-angled. From the point of view of ordinary, so-called “common” sense, such reasoning seems convincing. But the examiners rejected it because it contained a gross logical error. Knowledge of the theorems alone was not enough to successfully pass the exam. The examinee should not have violated the rigor of reasoning required in mathematics.

Failure associated with this kind of error can befall a person not only in the mathematics exam.

A student entering the institute writes an essay on literature on the topic “Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace” - the heroic epic of the struggle of the Russian people.” He outlines a plan that goes like this:

1. Introduction. Historical significance of the novel.

2. Presentation:

a) war in the novel,

b) people of war,

c) partisan movement.

3. Conclusion.

No matter how well the applicant knows this material, no matter what he writes in his essay, already in advance, only on the basis of familiarity with the plan can one say that his work as a whole will be considered unsatisfactory. And this will be the result of a logical error made in the plan.

In the tenth grade of one of the Moscow schools, students were asked to answer in writing the question whether they should study geography. Among the many varied answers, one of the most typical was the following:

“The study of geography is necessary in order to give us the opportunity to learn, through the study of physical geography, about the surface, climate, vegetation of places where we have not been and, perhaps, never will be. And from economic geography we learn about the economy, industry, and political system of a given country. Without geography, we wouldn’t be able to travel around the country.” This answer also contains a serious logical error.

All the examples given here are taken, as we see, from completely different areas of knowledge. However, in all three examples the errors are of the same nature. They are called logical.

What is the essence of these errors?

If a person looking at the railway tracks going into the distance seems to be converging on the horizon at one point, then he is mistaken. The one who thinks that the fall of one grain to the ground does not make the slightest noise, that a piece of fluff has no weight, etc. is mistaken. Can these errors be called logical? No. They are associated with deception of vision, hearing, etc., these are errors of sensory perception. Logical errors relate to thoughts. You can also think about objects that you cannot see, hear, or touch at the moment, that is, you do not perceive sensually. We may think that the Earth revolves around the Sun, although we do not directly experience it. At the same time, our thoughts can correspond to reality, that is, be true, and they can contradict the real situation of things, that is, they can be erroneous, untrue.

Errors related to thoughts are also not always logical. The child can say that two and two are three. During an exam, a student may incorrectly name the date of an event. Both of them make a mistake in this case. If the reason for these errors is only poor memory, for example, a child does not remember the multiplication table, or a student has poorly learned chronology and forgot the required date, then the errors they made cannot be classified as logical.

Logical errors do not relate to thoughts as such, but to the way one thought is connected to another, to the relationships between different thoughts. Each thought can be considered on its own without connection with other thoughts. If such a thought does not correspond to the real state of affairs, then in this case there will be a factual error. The child and the student made exactly this kind of mistake. However, each thought can be considered in relation to other thoughts. Let’s imagine that a student who has forgotten the date of some event will not answer at random (“maybe I’ll guess!”), but will try, before answering the question, to mentally connect this event with some other facts known to him. He will establish in his mind a certain relationship between the thought of a given event and the thoughts of those facts with which he wants to connect this event. These kinds of connections between thoughts are constantly being established. The idea that a dolphin breathes with its lungs is associated with the idea that a dolphin is a mammal, and all mammals breathe with their lungs. Knowledge about the force of gravity gives people the confidence that a stone cannot, on its own, without any outside influence, lift off the ground and fly into the air. In our example, if the student’s thought about the facts with which he wants to connect this event corresponds to reality and he establishes the connection between his thoughts correctly, then, even forgetting the chronology, the student can give the correct answer to the question posed. However, if in the process of his reasoning he establishes a connection between the thought about a given event and thoughts about these facts that does not actually exist, then, despite knowing these facts, he will give the wrong answer. An error in the answer will be the result of an error in reasoning, which will no longer be a factual error, but a logical one.

We said that the connection between thoughts that a person establishes may or may not correspond to the connection between them that actually exists. But what does “really” mean? After all, thoughts do not exist outside a person’s head, and they can communicate with each other only in a person’s head.

Of course, there is absolutely no doubt that thoughts are connected with each other in a person’s head in different ways, depending on the state of the psyche, on the will and desires. One person associates pleasant thoughts about skating and skiing with the thought of the approaching winter. For another, the same thought evokes completely different, perhaps less pleasant thoughts. All such connections between thoughts are subjective, that is, depending on the psyche of each individual person. It will also depend on the mental characteristics of different people whether a person will establish a connection between the thought of a lake freezing in winter and the thoughts that in winter the temperature drops below zero and water freezes at this temperature. However, regardless of whether a person thinks about it or not, whether he connects or does not connect these circumstances with each other, whether it is pleasant or unpleasant for him, from the truth of the thoughts that water freezes at temperatures below zero and in winter the temperature is below zero, inevitably, objectively, completely independent of subjective tastes and desires, the truth of the idea that the lake freezes in winter follows.

Whether a thought arises in a person’s head or not, what kind of thought arises, how it connects with other thoughts - all this depends on the person. But the truth and falsity of thoughts do not depend on it. The proposition “twice two equals four” is true regardless of any characteristics of the psyche and structure of the brain of different people. It is also objectively true that “The Earth revolves around the Sun”, “The Volga flows into the Caspian Sea”, and it is objectively false that “The Earth is larger than the Sun”. But if the truth and falsity of thoughts do not depend on a person, then, naturally, there must be relations between the truth and falsity of various thoughts, independent of the will and desire of people. We saw such relationships in the examples above. The existence of these objective connections in thoughts is explained by the fact that thoughts and relationships between them reflect objects and phenomena of the world around us. Since objects and connections between them exist objectively, independently of a person, the connections between thoughts reflecting objects and phenomena of the external world must be objective and independent of a person. Therefore, recognizing as true the thoughts “a dolphin is a mammal” and “mammals breathe with their lungs,” we will have to recognize as true the thought that “a dolphin breathes with their lungs.” The truth of the last thought is objectively related to the truth of the two previous ones.

At the same time, such a connection does not exist between such three thoughts as “2 + 2 = 4”, “The Earth revolves around the Sun” and “Ivanov is a good student”. The truth of each of these propositions is not determined by the truth of the other two: the first two may be true, but the third may be false.

If an individual incorrectly reflects in his thoughts the relations between things, then he can also distort the relations between the truth and falsity of various thoughts. Such a distortion would occur if someone connected the above thoughts “2 + 2 = 4”, “The Earth revolves around the Sun” and “Ivanov is a good student” with each other and decided that the truth of the first two of them determines the truth of the third , or, conversely, would deny such a connection between the thoughts “all mammals breathe with their lungs,” “a dolphin is a mammal,” “a dolphin breathes with its lungs.”

In order to distinguish cases when the relations directly between things, on the one hand, and the relations between thoughts, on the other, are distorted, two different words, two special terms are introduced. When there is a distortion of real world relations, we speak of untruth thoughts. Then, when we are talking about the distortion of the relationships between the thoughts themselves, they talk about irregularities.

In everyday life, it is usually believed that both these words, “untruth” and “wrongness,” mean the same thing. However, when applying them to reasoning, one must see a significant difference between them, which must be strictly taken into account when establishing connections between different thoughts. Each thought individually may be true, but the relationship established between them may be incorrect. For example, each of the three thoughts “2 + 2 = 4”, “The Earth revolves around the Sun” and “The Volga flows into the Caspian Sea” is true. But the idea that from the truth of the proposition “2 + 2 = 4” and “The Earth revolves around the Sun” should the truth that “the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea” is incorrect. All statements are true, but the idea that there is a connection between them is wrong.

Errors associated with the untruth of thoughts, i.e., with a distortion in thoughts of the relationships between objects and phenomena of the surrounding reality, are called factual. Errors associated with the incorrectness of thoughts, that is, with the distortion of connections between the thoughts themselves, are logical.

Actual errors may be relatively larger or smaller. “2 + 2 = 5” is a less serious factual error than “2 + 2 = 25.” However, both big and small are mistakes, since in both the first and second cases the thought turns out to be untrue. The same applies to logical errors. The argument “2 + 2 = 4, therefore, hippos live in Africa” asserts a connection between thoughts that clearly does not exist. The example with the Pythagorean theorem given at the beginning of the brochure also does not actually contain the connection between thoughts that the student established. There this lack of connection is not as obvious as in this example. However, the essence of the error in both cases is the same. In both cases there is a logical error, and less obvious errors can and do often do much more harm than clearly absurd ones.

II. What is the harm of logical errors?

In practical life, we are primarily interested in the question of how to find out whether a particular thought is true or false. In some cases, this can be established immediately, with the help of our senses - vision, hearing, touch, etc. In this way, you can check the truth of, for example, thoughts such as “there are three windows in this room”, “there is a tram going down the street” “The water in the sea is salty.” But what about such statements: “man descended from ape-like ancestors”, “all bodies are made of molecules”, “the universe is infinite”, “Peter is a good boy”, “smoking is harmful to health”? Here you cannot simply look and see whether these thoughts are true or false.

The truth of such statements can only be verified and proven by logical means, by finding out what relationships these thoughts have to some other thoughts, the truth or falsity of which we already know. In this case, the correctness or incorrectness of the reasoning already comes to the fore. The truth or falsity of the conclusion we make will depend on this. If the reasoning is constructed correctly, if exactly those connections that actually exist are established between these thoughts, then, being confident in the truth of these thoughts, we can be completely confident in the truth of the conclusion that is obtained as a result of the reasoning. But no matter how reliable the initial positions are, we cannot at all trust the conclusion if there is a logical error in the reasoning. Thus, the statement of an applicant to the institute that “this triangle is right-angled, because the sum of the squares of its two sides is equal to the square of the third” does not inspire confidence, and the answer of a 10th grade student about the need to study geography does not convince us. Both the applicant and the student make logical errors in their reasoning. Therefore, in no case can one rely on the truth of the position they justify, even if it does not lead to a factual error.

Such cases where incorrect reasoning does not lead to an error of fact are quite possible. For example, the above reasoning “2 + 2 = 4, the Earth rotates around the Sun, therefore, the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea” contains a clear logical error, obvious to everyone. However, the truth of the idea that “the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea” is equally obvious to everyone. A student entering the institute, claiming that a given triangle is right-angled, also does not make a factual error, nevertheless, the reasoning as a result of which he came to this thought is logically erroneous, although in this case the error is not so obvious that everyone could notice it. The fact that in this case the logical error is not obvious to everyone does not reduce, but increases its harm. After all, obviously absurd mistakes are made very rarely, and, in any case, they can be quickly corrected, since they are easy to detect. Usually the mistakes that are made are those that are not so obvious. They are the cause of numerous misconceptions, erroneous conclusions and often bad actions of people. Of course, not always and not all logical errors cause great harm. In some cases they can cause only a slight nuisance, some inconvenience, nothing more. For example, a teacher or housewife comes to the library to sign up and borrow books. There are four tables there. Each of them indicates the category of readers who are given books at a given table: at the 1st table - workers, at the 2nd - employees, at the 3rd - students, at the 4th - researchers. Which table should the teacher and housewife approach? A teacher can go to the 2nd and 4th tables with equal success; housewives can go to none of these four tables, although in this library they make up the majority of readers. A difficulty arises due to the illogical division of readers into categories. A similar difficulty can be encountered in the dining room if the menu is illogically compiled. A person wants to take a second meat dish, looks through the entire list of “Second courses” and does not find what he needs. Nevertheless, this dish is available in the 3rd section of the menu - “A la carte dishes”.

The trouble caused by a logical error is small in this case. Errors made in other reasoning can cause greater harm.

A group of students from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of the Pedagogical Institute argued that matter turns into energy, on the basis that it is written so in the “Concise Philosophical Dictionary”. This dictionary actually contains such words, but its authors did not make any mistakes, although the very idea of converting matter into energy is not only untrue, but completely absurd from a scientific point of view. The students themselves made a logical mistake in their reasoning: “all the provisions of the authors of the philosophical dictionary are correct, this thought was taken from the philosophical dictionary - that means it is correct.” A logical error led to an incorrect conclusion.

Considerable harm can also be caused by erroneous reasoning, for example, such as: “he blushed - that means he is to blame” or “if a person has a fever, then he is sick; Petrov’s temperature is normal, therefore Petrov is healthy.” As a result of such reasoning, a completely innocent person will be suspected and even accused of some very unseemly act, and a sick person, for whom bed rest is required, the doctor may send to work, which may cause an exacerbation of the disease.

Finally, there may be cases where undetected logical errors lead to serious crimes not only against individuals, but also against entire nations. Whether people commit these crimes because they themselves fall into error and draw incorrect conclusions, or they deliberately mislead others, taking advantage of their inability to distinguish logically correct reasoning from incorrect reasoning - in both cases, evil will be associated with the admission of logical errors in justification the truth of certain provisions and the inability of people to detect these errors.

III. What are the causes of logical errors?

Why do people make logical mistakes? What is the reason that in some cases, for example, in the reasoning “2 + 2 = 4, the Earth revolves around the Sun, therefore, the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea,” the logical error is clear to every sane person, and in examples with the Pythagorean theorem, the plan essays and questions about studying geography, many people do not notice the logical error at all?

One of the most important reasons here is that many wrong thoughts are similar to right ones. And the greater the similarity, the more difficult it is to notice the mistake. If the incorrect reasoning given at the beginning is compared with the correct one, the difference may not seem very significant. Many may not notice this difference even now, when their attention is specifically called to the difference in the connections between thoughts in this case and in the examples given at the beginning.

I. The fact that a triangle with sides 3, 4 and 5 is right can be deduced from the converse of the Pythagorean theorem. According to this theorem, if the square of one side of a triangle is equal to the square of the other two sides, then the triangle is right-angled. Here the following ratio is evident: 5 2 = 3 2 + 4 2. Therefore, this triangle is right-angled.

II. Essay plan “Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace” is a heroic epic of the struggle of the Russian people.”

Main part:

1. Actions of the regular Russian army.

2. People's support for the Russian army:

a) in the rear of the Russian army;

b) behind the invaders’ lines (partisan movement).

III. Why is it necessary to study geography? Studying geography helps to better understand the history of human development and the events currently taking place in our country and throughout the world.

The connection of thoughts in this case is fundamentally different from the connection that was established during the entrance exams at the university and by the 10th grade student. However, this difference is not obvious to everyone.

There are arguments in which a logical error is deliberately made and the relationships between thoughts are established in such a way that this error is difficult to notice. With the help of such reasoning, the truth of obviously false statements is substantiated. In this case, incorrect reasoning is so subtly given the appearance of correctness that the difference between right and wrong becomes invisible. Such reasoning is called sophistry. In ancient Greece there were sophist philosophers who were specifically engaged in composing sophisms and taught this to their students. One of the most famous sophistic arguments of that time is the sophistry of Euathlus. Euathlus was a student of the sophist Protagoras, who agreed to teach him sophistry on the condition that after the first trial Euathlus won, he would pay Protagoras a certain amount of money for his training. When the training was completed, Euathlus told Protagoras that he would not pay him any money. If Protagoras wants to resolve the case in court and the case is won by Euathlus, then he will not pay money, according to the court verdict. If the court decides the case in favor of Protagoras, then Euathlus will not pay him, since in this case Euathlus loses, and according to the condition he must pay Protagoras only after he wins the case. In response to this, Protagoras objected that, on the contrary, in both cases Euathlus must pay him: if Protagoras wins the case, then Euathlus naturally pays him according to the court decision; if Euathlus wins, then he must pay again, since this will be the first lawsuit he has won. Both arguments seem to be correct, and it is difficult to notice an error in them, although it is absolutely clear that both of them cannot be correct at the same time and at least one of them has an error.

Many examples of how completely incorrect reasoning is put into a form that is apparently strictly correct can be taken from the field of mathematics. Such reasoning includes, for example, the following.

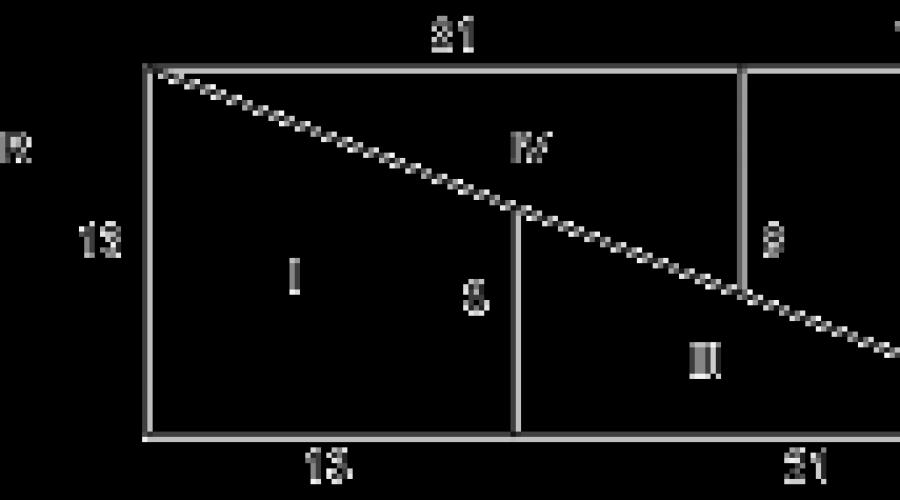

A square with sides 21 has the same area as a rectangle with sides 34 (= 21 + 13) and 13.

Rice. 1

Rice. 2

Square Q (Fig. 1) is divided into two rectangles measuring 13x21 and 8x21. The first rectangle is cut into two identical rectangular trapezoids with bases 13 and 8, the second rectangle is cut into two identical right triangles with legs 8 and 21. From the resulting four parts we fold a rectangle R, as shown in Fig. 2.

More precisely, we apply right triangle III to right-angled trapezoid I so that the right angles with a common side of 8 are adjacent - a right triangle is formed with legs 13 and 34 (= 13 + 21): exactly the same triangle is made up of parts II and IV; finally, a rectangle is formed from the resulting two equal right triangles R with sides 13 and 34. The area of this rectangle is 34×13 = 442 ( cm 2), while the area of the square Q, consisting of the same parts, is 21×21=441 ( cm 2). Where did the extra square centimeter come from? 2

Cm. Y. S. Dubnov, Errors in geometric proofs, Gostekhizdat, 1953, p. 10.

The entire course of reasoning, it would seem, strictly and consistently leads to the conclusion that the areas of the square and the newly obtained triangle should be the same, but meanwhile, upon calculation, it turns out that the area of one of them is greater than the area of the other. Why? Obviously, there is some kind of error in the reasoning, but not everyone will immediately notice it.

In the same way, you can “prove” that a right angle is equal to an obtuse angle, etc. 3

See ibid., pp. 17-18.

A person's ability to notice the difference between right and wrong thoughts depends on the attention he directs to those thoughts. Everyone knows that the more attention we focus on a particular object, the more we notice in it details that escape during a more superficial, inattentive examination. But it’s not just the degree of attention that matters here. Where this attention is directed plays a more important role. This is well known to illusionists and magicians. Their success depends on the extent to which they manage to divert the audience's attention from some details and focus on others.

What does the focus of attention depend on? In answering this question, we have to talk not so much about thoughts themselves, but about a person’s attitude towards certain thoughts. The direction of attention depends primarily on people's interests.

V.I. Lenin in one of his works cites an old saying that if geometric axioms affected the interests of people, they would probably be refuted. 4

Cm. V. I. Lenin, Soch., vol. 15, p. 17.

Every person living in a class society expresses the interests of one or another class, one or another group of people.

The fact that many modern bourgeois ideologists attack Marxism, trying to refute it by all means, is not accidental. Marxism is the ideology of the working class. This teaching reveals the true causes of capitalist exploitation and leads the working class to build a society without exploiters and the exploited. It is quite natural that people interested in preserving their class rule try with all their might to directly or indirectly refute and distort Marxism.

Of course, one cannot think that in all cases class interest is clearly recognized. Very often, a person who expresses certain class interests does not at all set himself the premeditated task of defending these interests, much less using logical errors for this purpose. But this ultimately does not change the essence of the matter. Consciously or unconsciously, a person, under the influence of his interests, strives to obtain some conclusions and discard others. This leads to the fact that in reasoning, the conclusions of which correspond to his desire, a person may not notice a rather gross logical error, and in reasoning that contradicts his interests, it is relatively easy to detect a less obvious illogicality.

Everything that has been said here about the role of interest applies, of course, not only to those cases when it comes to class interest, but also to simpler, special cases. The difference in interests between Euathlus and Protagoras was not class. The logical error in their reasoning is due to the private desire of each of them to receive a certain monetary benefit. The influence of such private interest on people's reasoning can be observed constantly. Fiction gives us numerous examples of this. It is enough to recall at least the well-known story by Chekhov “Chameleon” or some passages from Shakespeare’s tragedy “Hamlet”, for example, the conversation about clouds between Hamlet and Polonius.

Hamlet: Do you see that cloud in the shape of a camel?

Polonius: By God, I see, and indeed, it’s like a camel.

Hamlet: I think it looks like a ferret.

Polonius: Correct: the back is ferret-like.

Hamlet: Or like a whale.

Polonius: Exactly like a whale. 5

W. Shakespeare, Selected Works, Gihl, 1953, p. 271.

Polonius, as a courtier, does not want to contradict the prince and therefore contradicts himself.

Very good examples of the influence of interest on the direction of reasoning are provided by oriental tales about Khoja Nasreddin, for example, the tale of how Nasreddin asked his rich and stingy neighbor to give him a cauldron for a while. The neighbor complied with his request, although not very willingly. Returning the cauldron to the owner, Nasreddin gave another saucepan along with it, explaining that the cauldron gave birth to this saucepan, and since the latter belongs to the neighbor, then, in Khoja’s opinion, the saucepan should also belong to him. The neighbor fully approved of this reasoning and took the saucepan for himself. When Nasreddin asked him for a cauldron again, he gave it to him much more willingly than the first time. However, a lot of time passes. Khoja does not return the boiler. Having lost patience, the neighbor himself went to Nasreddin and demanded the cauldron from him, to which he replied: “I would be happy to return the cauldron to you, but I can’t, because he died.” - "How! – the neighbor was indignant. “Why are you talking nonsense - how can a boiler die?!” “Why,” answered Nasreddin, “can’t a cauldron die if it can give birth to a saucepan?”

Interest in certain conclusions, the desire to prove oneself right at all costs often causes a person to have strong internal excitement, excite his feelings, or, as psychologists say, lead him into a state of passion, under the influence of which he very easily makes logical mistakes . The more violent the dispute, the more mistakes there are on both sides. In the occurrence of errors, affects caused by love, hatred, fear, etc. are of great importance. A mother, lovingly watching every movement of her child, can see a manifestation of extraordinary development and even genius in his actions, which she simply does not see in other children. will notice. Under the influence of fear, some things or phenomena may appear to a person in a completely distorted form. No wonder they say that “fear has big eyes.” Hatred of a person makes you suspect evil intent in every most innocent word or deed. A striking illustration of such a biased assessment of a person under the influence of passion is the appeal to court by the hero of Gogol’s work “The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich.”

“...The above-depicted nobleman, whose very name and surname inspires every kind of disgust, harbors in his soul the malicious intention of setting me on fire in his own house. Undoubted signs of this are evident from the following: firstly, this malignant nobleman began to often leave his chambers, which he had never done before, due to his laziness and vile obesity of his body; 2, in his people's room, adjacent to the very fence enclosing my own, which I received from my late parent, Ivan, son of Onisius, Pererepenok, of blessed memory, the earth, a light burns daily and for an extraordinary duration, which is already obvious to that proof, because before this, but due to his stingy stinginess, not only the tallow candle, but even the Kagan was always extinguished.” 6

N.V. Gogol, Collection soch., vol. 2, Gihl, 1952, p. 218.

From all that has been said, it is clear that under the influence of emotions and affects, the right can seem wrong and, conversely, the wrong and even the absurd can seem right. As a result, it is necessary to distinguish between two sides:

a) correctness or incorrectness of thoughts by themselves;

b) to what extent do people feel and realize this rightness or wrongness.

In accordance with these two points, the distinction of which is very important, in relation to each reasoning we can speak, on the one hand, about its evidence, on the other hand, about him persuasiveness. Evidence is associated with the first of these two aspects, persuasiveness with the second. Incorrect reasoning can sometimes lead people to believe that it is correct, that is, to be convincing without being demonstrative. On the contrary, ideally correct, absolutely free from any errors, that is, evidence-based reasoning may turn out to be unconvincing for some people. The latter especially often happens when what is being proven contradicts the interests, feelings and desires of these people.