Sloboda history of origin and development. The emergence and development of Sloboda Ukraine. The purpose of creating the Euroregion "Slobozhanshchina"

Mar 10 1919

Sloboda Ukraine(also - Sloboda Ukraine, Sloboda suburb , Sloboda region, Slobodskaya notch line, or Slobozhanshchina; Ukrainian Slobidska Ukraine) - a historical region in the northeast of modern Ukraine and the southwest of the Central Black Earth economic region of Russia (in the Russian Empire, Slobozhanshchina was entirely part of the Little Russian economic region [ ]).

Pre-Mongol period

In those days, the steppe part of the territory of Slobozhanshchina was part of a large territory called the Polovtsian steppe, or Desht-i-Kypchak.

It was on the territory of Sloboda in 1185 and 1186 that the action of the "Word about Igor's regiment" took place.

See also History Kharkov, History Belgorod oblastMongol invasion

In the first half of the XIII century, during the Mongol-Tatar invasion, Donets and other Slavic settlements were destroyed, and the region was devastated. From the middle of the XIII century, these lands went to the Golden Horde, and after the battle on the Blue Waters in 1362, they became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

16th century

Since the 16th century, most of the lands of modern Slobozhanshchina have become part of the Moscow principality following the results of the Russian-Lithuanian war of 1500-1503.

The territory of Sloboda Ukraine at that time was an almost deserted “Wild Field”, through which the Tatars raided deep into the Muscovite state - usually along the Muravsky Way (he led the watershed between the Dnieper and Don - from Perekop to Tula), as well as its branches - Izyumsky and Kalmiussky sakmami.

Settlement of Slobozhanshchina

Starting from the end of the 16th century, this territory of the Russian state was re-populated both by Russian settlers (they founded Belgorod (in a new place), Chuguev, Tsarev-Borisov, Mayatsk, all the cities of the Belgorod notch line, Russian Lozovaya, Russian Tishki, etc.), and settlers-peasants and Cossacks from the Russian, Kyiv, Bratslav voivodeships of the Commonwealth. The bulk of these settlers were Cossacks, peasants, clergy, who fled from the Polish gentry. A very small part of the settlements (in the west of the present Sumy region) was founded by officials of the Commonwealth (Akhtyrka, Oleshnya) - before their peaceful transfer to the Russian state through the Polyanovsky world in 1635-1648.

For the Russian kingdom, Slobozhanshchina was a continuation of the Zasechnaya line as the protection of the southern borders of the kingdom from the Crimean and Nogai Tatars, which is why the tsarist government exempted the settlers from paying taxes, allowed distillation (there was a vodka farm on the main territory of Russia) and allowed them to freely engage in profitable trades (for example, salt mining). ). The settlers owned a certain amount of free land free of charge (the right to borrow), they retained Cossack privileges and self-government.

Along with the settlement, temples are being actively built here, many monasteries arise - Svyatogorsky, Divnogorsky, Kholkovsky, Shatrishchegorsky, Akhtyrsky, Trinity, Krasnokutsky, Cossack, Zmievskaya, Kuryazhsky, Khoroshevsky, Nikolaevsky, Ostrogozhsky female and others. With the help of the brotherhood, education develops. In 1732, 124 schools operated in four regiments of Slobozhanshchina.

Founded in the 17th century as fortresses Kharkov, Sumy, Sudzha, Akhtyrka, Ostrogozhsk turned into trade and craft centers in the 18th century. Akhtyrskaya tobacco, Glushkovskaya cloth and other manufactories arose here. There were big fairs in Kharkov and Sumy.

In 1731-1733, to protect the borders of the Russian Empire from Tatar raids, a system of fortifications, the Ukrainian Line, was built by the efforts of the left-bank and suburban regiments and peasants.

natural conditions

Slobozhanshchina is a territory over which small hills extend in some places. Above others on the territory of Ukraine is the northern part of the Kharkiv region with the Nagorny district of Kharkov, which is a part of the Central Russian Upland, expanding towards Belgorod.

The settlement of the "Wild Field" was significantly influenced by local rivers. Now none of them is navigable, but it used to be different. Many ships with bread were rafted along the Seversky Donets from Belgorod to Chuguev, and from there they sailed to the Don. Dnieper branches - Psel, Sula, Vorskla connected Sloboda with Poltava; the Seim river, which flows into the Desna, made it possible to communicate with the Chernihiv region. On the territory of Slobozhanshchina, the Dnieper rivers converge with the Don ones. Slobozhans first of all began to settle where there was more water. The reason that the western parts of the region are more densely populated and earlier than the eastern parts is that there were fewer rivers in the east.

But since the 18th century, the Slobozhansky rivers begin to shallow every year, as the forest area has significantly decreased and thinned out. There were disproportionately more forests at the time of settlement than at present. Forests and glades alternated along the entire coast of the Seversky Donets from Oskol to Zmiyov, dense forests also stretched on the banks of the tributaries of the Donets, sometimes along both banks: Izyumsky, Mokhnachsky, Teplinsky, etc. The forest was used to build both fortresses and fortifications, and everything necessary on the farm, in particular windmills, mills and distilleries.

On the territory of Slobozhanshchina, fruit trees and shrubs, as well as gardens with apiaries, are widespread. There were birds, wild animals (bisons, bears, wolves, elks, wild boars), furs; saigas and wild horses met in the steppes. There were few minerals. In excess there was only salt, which was mined on the Torsk lakes. They also mined stones for millstones, chalk, which was used for the construction of "hut-huts", pottery clay. The soils are fertile black earth. In the wide steppes it was easy to breed herds of horses, cattle, and sheep.

Administrative-military structure

From the moment colonization began in the middle of the 17th century and until the second half of the 18th century (1764), Slobozhanshchina had self-government, somewhat similar to the Hetmanate. In other words, there was a regimental-hundred structure, where the regiment was simultaneously both a military and a territorial unit. There were five regiments in total: Ostrogozhsky (otherwise - Rybinsk), Kharkov, Sumy, Akhtyrsky and Izyumsky. In contrast to the Hetmanate, the Sloboda regiments did not have military or koshevoi chieftains, and all military, administrative and partially judicial power on the territory of the regiment belonged to the Cossack colonel. He had with him the symbols of power of the regiment: seal, timpani, regimental banners. The military and civil administration was made up of a regimental foreman (an analogue of an officer): a baggage officer, a judge, a captain, a cornet, and two clerks who were members of the regimental Council.

All five suburban regiments were divided into hundreds, of which there were 98 in 1734. The hundred management was carried out by the centurion, ataman, captain, cornet and clerk. Each ten had a ten's manager. Such a system of power was marked by two characteristic features: the selectivity of the foreman, but at the same time a rigid hierarchy of paramilitary power.

In operational terms, the suburban colonels were subordinate to the Belgorod voivode, appointed from Moscow (later - from St. Petersburg), relations with which were far from cloudless. The colonels did not always get along with each other. For example, in 1664, Colonel Yakov Chernigovets emigrated to Slobozhanshchina (an opponent of the right-bank hetman Pavel Teteri), founded the city of Balakleya, which became the center of the new Balakleysky regiment. In 1666, having left the atamanism for a while, Ivan Sirko returned from Zaporozhye to Slobozhanshchina in order to lead the newly established Zmievsky regiment, which separated from the Kharkov regiment (in 1671 the Zmievsky regiment was again attached to the Kharkov regiment). Sirko also raised an uprising against the king and "fought the outlying cities", in particular, Kharkov, which he besieged, but could not capture.

Fight against Tatar raids

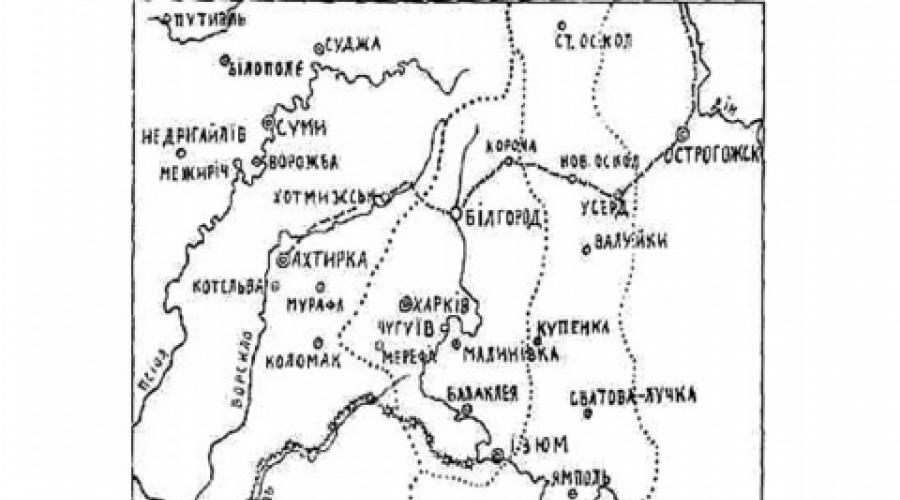

The need for settling Slobozhanshchina can be seen on this map. The wild field formed a corridor for nomadic Tatars between the Don Cossacks and the Hetmanate. Through it, the Tatars knew the paths to the populated part of the Muscovite kingdom well and chose those that did not have to be melted down through deep and wide rivers. They even gave names to some fords. The ancient "Book of the Big Drawing" lists eleven such fords - Kagansky, Abashkin, Shebelinsky, Izyumsky, Tatarsky and others. Many well-known paths in the Wild Field were also laid by the Tatars. The widely known Muravsky Way started from the Crimean Perekop and lay to Tula (and this is only 160 versts from Moscow) along the interfluve of the Don and Dnieper water intakes. The very name of the path is Tatar, since in an ancient document a Tatar named Muravsky is remembered. Izyumsky and Kalmiussky ways branched off from Muravsky - the first one entirely, and the second for the most part ran through the territory of Kharkov region.

Colonels were of great importance in the life of the suburban regiments. A distinctive feature was that in Slobozhanshchina the post of colonel was for life. A trend developed very quickly when the regiments were in the hereditary management of local foremen's clans. During the absence for one reason or another of the colonel, he was replaced by the appointed colonel. Also, the regimental foreman was: regimental judge (headed the court in the regimental town hall), esaul (assistant to the colonel for military affairs), cornet (headed the colonel's security and kept the regimental banner-gonfalon), 2 clerks (for military and civil affairs).

The population of Sloboda Ukraine was not homogeneous in terms of their rights and social status. The privileged class were the Cossacks, who had the right to own land for military service and free trade, and also did not pay taxes. The peasants remained "commonwealth" and paid taxes. A feature of their life in Slobozhanshchina was the right to move to a new owner and to new lands. Only in 1783 serfdom was established in the region. The philistines used the Magdeburg law, which gave them great legal opportunities: city self-government and courts, a monopoly on trade in the city.

In the Russian Empire

From 1816 to 1819, the first mass popular magazine "Ukrainian Vestnik" (founded by Evgraf Filomafitsky) was published in Kharkov, which initiated the practice of printing scientific materials in Ukrainian, which was then considered "Little Russian (Little Russian) dialect". In 1834, "Little Russian Tales" by Grigory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, who was called "the father of Ukrainian prose", was published in Kharkov. A Ukrainian poetic circle of “Kharkov romantics” operated in Slobozhanshchina, which included Ambrose Metlinsky, Levko Borovikovsky, Alexander Korsun, Mikhail Petrenko and others who wrote mainly in Russian. The almanacs “Young[s]k”, “Ukrainian Almanac”, “Sheaf” were published, in which the works of Peter Gulak-Artemovsky, Evgeny Grebyonka, Yakov Shchegolev, Mikhail Petrenko were published. A folklore collection by Izmail Sreznevsky "Zaporozhian antiquity" (1833−1838) and an article "A look at the monuments of Ukrainian folk literature" were published in Kharkov - the first printed public speech in defense of the Ukrainian language. The author of popular historical novels G. P. Danilevsky was born and lived a significant period of his life in the Kharkov province, his first major prose work was the collection “Slobozhane. Little Russian stories” is dedicated to the native land.

Nikolay Kostomarov began his scientific career in Kharkov by researching South Russian and Slobozhan history and the history of writing. In the 1810s-40s, the first works on the history of Sloboda Ukraine appeared, in particular Ilya Kvitka "Notes on the Sloboda regiments from the beginning of their settlement until 1766" (1812); Izmail Sreznevsky - "Historical image of the civil dispensation of Sloboda Ukraine" and the above-mentioned Grigory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko - "Historical and statistical essay on Sloboda", "On the Sloboda regiments", "Ukrainians" and "History of the theater in Kharkov"

The church history of Slobozhanshchina was studied by Archbishop Filaret (Gumilevsky), who headed the Kharkiv diocese from 1848 to 1859.

In the second half of the 19th century, scientific research on the theory of literature, folklore and ethnography, mainly general linguistics, phonetics, morphology, syntax, semasiology was carried out by Professor of Kharkov University Alexander Potebnya and his student Nikolai Sumtsov. They did a lot in the field of Slavic dialectology and comparative historical grammar. In general theoretical terms, A. Potebnya mainly investigated the issues of the relationship between language and thinking, language and nation, and the origin of language. He also owns works on the Ukrainian language and folklore. Historians Dmitry Bagalei, Peter and Alexandra Efimenko worked in Kharkov.

Artists I. N. Kramskoy and I. E. Repin were born in Slobozhanshchina.

In 1835, the Sloboda-Ukrainian province was abolished again. In its place, the Kharkov province was created, which consisted of 11 counties: Kharkov, Bogodukhovsky, Sumy, Valkovsky, Starobelsky, Volchansky, Akhtyrsky, Zmiyovsky, Izyumsky, Kupyansky, Lebedinsky. Some border areas went to the Voronezh and Kursk provinces. In the Kharkov province, about 60% of the land was owned by landlords, state and monastic property. The largest landowners are Kharitonenko, Koenigi. 36% of peasant farms were landless. In 1817, over 17 thousand state peasants and military inhabitants of Kharkov, Izyum, Zmiev districts were assigned to military settlements, which caused uprisings (Chuguev uprising of 1819, Shebelinsky uprising of 1829).

After the abolition of serfdom (peasant reform 1861 ), market relations developed rapidly. At the end of the 19th century, Slobozhanshchina occupied one of the leading places in southern Russia in the production of industrial products. There were more than 900 industrial enterprises here. Large transport engineering enterprises were built -

Sloboda Ukraine (Sloboda Ukraine) - a historical region that was part of Russian state of the XVII-XVIII centuries (the territory of modern Kharkov, and also parts of the Sumy, Donetsk, Lugansk regions of Ukraine, Belgorod, Kursk and Voronezh regions of Russia).

Pname origin

Slobozhanschina in 1667-1687

The word "sloboda", according to the "Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language" by V.I. Dalia means "village of free people". This is where the names Sloboda Ukraine and Sloboda Ukraine come from. Now it is a territory covering most of Kharkov, east of Sumy, north of Lugansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine and border regions of Belgorod, Kursk and Voronezh regions of the Russian Federation.

Heiress of the Wild Field

Traces of the oldest settlement of Slobozhanshchina come from the early Paleolithic. At first, Slobozhanshchina was part of the territory of the northerners, from the end of the 9th century it became part of the Kyiv state, in the 11th century. to Chernigov, and later Pereyaslav and Novgorod-Seversk principalities. After the Tatar-Mongol invasion of the XIII century. the region is empty. From the beginning of the XVI century. Slobozhanshchina becomes part of the Moscow Principality. The territory of Slobozhanshchina was by that time almost uninhabited Wild Field, through which the Tatars raided deep into the Muscovite state - of course, along the Muravsky Way (he led the watershed between the Dnieper and Don - from Perekop to Tula), as well as its branch - the Izyumsky and Kalmiussky Ways On Slobozhanshchina deep into the steppe went Ukrainian industrialists - "goers", "dobichnikiv", who were mainly engaged in beekeeping, fishing and hunting, as well as the extraction of saltpeter and salt (on the Torsk lakes and in Bakhmut).

Exploration of the Wild Field

Sloboda Ukraine in the XVII-XVIII centuries. - until 1765

From the second half of the 16th century, refugees began to move from Ukraine-Rus, which was then under Poland, to the east, in areas that were considered the territory of Russia. They left, fleeing the Polish-Catholic aggression, not only a few, or individual families, but entire groups, often several hundred people or even several hundred families. Moscow willingly accepted them and helped in every possible way to settle in a new place, giving out help in kind and money, and allocating good land for settlement. They settled in the then deserted, richest lands, within the pre-revolutionary Kharkov province and adjacent counties of the Voronezh and Kursk provinces. These lands were to the south behind the row of border fortresses created by Moscow against the raids of the Tatars, the so-called "Belgorod line", which stretched (from west to east) from Akhtyrka, through Korocha and Novy Oskol, to Ostrogozhsk and rested on the upper reaches of the Don. The possibility and likelihood of Tatar raids, which during their attacks on Moscow usually passed through these lands, forced the new settlers to organize to repel these raids, creating, following the model of the Hetmanate, Cossack regiments and hundreds. Moscow, for carrying out this military service and guarding the borders, freed the new settlers from all taxes and duties and helped them with weapons and ammunition.

In 1732, these regiments were renamed into dragoon regiments, but this reform caused discontent among the suburban Cossacks, who valued the old traditions of the Cossacks, and therefore, with the accession of Empress Elizabeth, who favored the Ukrainians, in 1743, these regiments were again turned into Cossack ones. Only in 1764, after the abolition of the hetmanship on the Left Bank, the suburban Cossack regiments were finally turned into hussar regiments of the regular cavalry of the Russian army. The foremen of these regiments turned into hereditary nobles of the Russian Empire, like the Cossack foreman of the Left Bank.

The social structure of Sloboda

Russian empire

The social structure of Sloboda Ukraine basically changed in the same way as on the Left Bank. The refugee mass that arrived from Ukraine-Rus was homogeneous and free. With the organization of military units (for the protection of the southern borders), a foreman stands out from this mass - a privileged group. The rest of the mass, in the process of further administrative and military organization of Slobozhanshchina, is divided into Cossacks and free settlers. Gradually, a number of obligations are imposed on the free settlers. First, in relation to the foreman, and then, in relation to other layers of the Cossacks, with their transformation into the so-called "state peasants". descendants, or, “granted” by the Russian empresses to individuals. This is how landowners were created in Sloboda Ukraine. The urban population of Slobozhanshchina was extremely small, because the young, recently founded cities were also small. It consisted of persons involved in the administrative apparatus (military, officials), the clergy, merchants and artisans. Unlike the Left Bank, where the urban population was exclusively from the local population, there were many Great Russians in the cities of Sloboda Ukraine. There were no Jews in Sloboda Ukraine then.

In the field of cultural life of the population, Sloboda Ukraine, which was initially busy with organizing life in new places, did not show itself in anything special and did not create any cultural centers, monasteries or well-known schools. They were content with what came either from the Dnieper region or from Great Russia, constructively combining both influences and gradually merging with the all-Russian cultural life. The separatists call this process “forced Russification.” But they do not cite any evidence of “violence” and hush up that the question is about the cultural life of the refugees who moved to Great Russia (the Muscovite kingdom), that is, to another, at that time, state. And, of course, it is natural that the Moscow governors and service people who were in the territory where the refugees settled were in no hurry to adopt their language and way of life from the refugees.

The “Moscow people” did not interfere at all with the everyday side of life, the customs, the customs of the settlers, without preventing them from maintaining their way of life, the cut of clothes, forelocks, mustaches and “settlers”, without forcing them to let go of their beards in the Moscow fashion, but they did not shave their beards either. and forelocks were not released to please the settlers. In the cultural field, there is also no evidence of "violence" or the forced use of the "Moscow" (Great Russian) language. Each of them spoke with the settlers in their own language and, to the general joy,

made sure they understood each other perfectly. The trial (without any interpreters) was carried out on the basis of Moscow laws, binding on the entire territory of the Muscovite kingdom, including the lands provided for settlement by refugees from the Dnieper region.

The separatists see “forced Russification” in this, completely forgetting the fact that nowhere and never, immigrants to another country, do not organize their court according to their own laws, but obey the laws of the country that adopted them. As a result of all social processes, administrative measures and joint life with the Great Russians, by the end of the 18th century, Sloboda Ukraine was firmly merging with the rest of Russia, while maintaining its Ukrainian domestic and national characteristics.The organization of the national economy in Sloboda Ukraine was similar to that in the Hetmanate. agriculture and related cattle breeding. The dominant system of agriculture was variable; in the second half of the 18th century, a three-field system also began to spread. In addition to Cossack and peasant small land ownership, high society (Cossack elders and Russian nobility, as well as monasteries) possessions developed, sometimes reaching the size of latifundia.

A significant place in Sloboda Ukraine was occupied by sheep breeding (in the 13th century, also fine-wooled), beekeeping, gardening, fishing, milling, distilling, dektyarstvo) and various crafts and handicrafts (at the end of the 18th century, about 34,000 artisans and handicraftsmen were recruited in Sloboda Ukraine ). A prominent place was occupied by the salt industry (Torsk, Bakhmut and Spivakovsky plants).

In the XVIII century. manufactories appear, in particular the Chuguevskaya leather manufactory of F. Shidlovsky (born in 1711), the official tobacco one in Akhtyrka (1719), the Saltovskaya cloth Count Gendrikov (1739), and the linen centurion. Akhtyrsky regiment of Semen Nakhimov (1769), silk factories in the city of Novaya Vodolaga (end of the 18th century), etc. The cells of trade were fairs, of which there were 271 in 1779, mostly of a local nature, barely 10 medium and only 2 large - in Sumy and Kharkov. Of great importance was the transit trade through Sloboda Ukraine, which became an intermediary in trade between Russia, on the one hand, and the Hetmanate, Zaporozhye and Southern Ukraine, Crimea and the Don, the Caucasus and Iran, on the other. In particular, lively trade relations were between Sloboda Ukraine and the Hetmanate. Salt from the Torsky and Bakhmut salt works went from Sloboda Ukraine to the Hetmanate, industrial products, in particular glass, ironmongery, potash, vodka, etc., went from the Hetmanate to Sloboda Ukraine.

The political life of Sloboda Ukraine was limited by the Moscow state, and later by the Russian Empire, of which, although semi-autonomous, it was a part. But already the geographical position of Sloboda Ukraine between Moscow and the Crimean Khanate, Moscow and the Don, and especially Moscow and the Hetmanate more than once drew Sloboda Ukraine into the contradictions of the Eastern politics of that time. Sloboda Ukraine was the territory of devastating Tatar attacks from the south, which continued until the Russian-Turkish war of 1769–74 and the Kuchuk-Kainarji peace treaty of 1774. Sloboda Ukraine suffered great destruction (especially its western part – Sumy and Okhtyrshchyna), when in the winter the hostilities of the Swedish and Moscow troops spread to Sloboda Ukraine, which Charles XII considered as enemy territory. The Russian-Turkish war of 1735-39 also brought great damage to the economy of Sloboda Ukraine. conflicts between Sloboda Ukraine and the Moscow government, and sometimes caused riots and even uprisings of Sloboda residents against Moscow. In 1670, an uprising broke out in the Ostrogozhsky regiment, associated with the war led by Stepan Razin. The uprising, which was led by the old colonel Ivan Dzikovsky. It was soon suppressed, and Dzikovsky and his wife Evdokia, along with most of the rebels who were captured, were executed. The population of Sloboda Ukraine also took part in the K. Bulavin uprising of 1707-08, but the Sloboda regiments, together with some regiments of the Hetmanate, were forced to help Moscow pacify the uprising.

When in 1711 the Crimean Khan Devlet-Girey attacked Sloboda Ukraine (the Tatars then destroyed Bakhmut, captured Zmiev, Staraya Vodolaga and Merefa and devastated the regions of Izyum and Kharkov), the population of both Vodolagas, led by a foreman, joined the Tatars, for which Peter I ordered " execute the tenth by lot, and send all the rest with their wives and children to Moscow for exile. The Gaidamak uprisings in the Right-Bank Ukraine also had reviews in Sloboda Ukraine, but here they had a predominantly social (and then local) character.

Loss of autonomy

Reunification of Ukraine with Russia

The Sloboda regiments faithfully carried out, often very difficult, border service and participated in many campaigns and battles of the Russian army, distinguished by exemplary courage and stamina, for which they often received the approval of the highest authorities. In the battle of Gross-Egersdorf in the Prussian war, the Sloboda regiments rushed into a desperate attack on the Prussians and, falling under fierce grapeshot fire, suffered heavy losses in people and horses, but with this attack the Cossacks greatly helped the success of Russian weapons and once again testified to their hereditary courage.

The Sloboda Cossacks fought just as bravely and selflessly even earlier, near Azov, being among the tsarist troops, for which they were praised by Tsar Peter the Great himself, who, for Cossack merits, ordered in 1700 to release the “assistants” from paying a special tax to the treasury of the state. 1 ruble per year from the soul and determined the annual set of Sloboda regiments at 3,500 Cossacks. The Cossack service at that time was difficult and dangerous, the Cossacks received almost no salary and assistance from the government, but, despite these unfavorable conditions for the farmer, the Cossacks valued their knightly name more than anything else and faithfully kept the oath given to the king. For the loyalty and courage of the Sloboda Cossacks, Peter the Great granted them a letter confirming all their former rights and privileges.

Peter the Great, in the transformations of the whole of Russian life in general, did not leave Slobozhan alone either, ordering that the regiments be subordinated to the management of the Military Collegium and to direct command, appointing a special regular commander, who was given the right to promote the regimental foreman to the ranks and perform the functions of a military ataman, in however, on a very limited scale.

In 1731, the so-called Ukrainian line was arranged, the purpose of which was to serve as an obstacle to the invasion of the Russian borders of the Tatar gangs. According to the arrangement of this line, there was a need for huge excavation work on the embankment, the construction of trenches at individual forts and pickets. All this work was carried out by the Little Russian and Sloboda Cossacks appointed for this purpose, thus protecting peaceful Russian landowners from Tatar robberies. The reign of Anna Ioannovna was a difficult era for the Sloboda Cossacks, who for some reason did not like the proud and all-powerful German Biron at the Court.

By 1735, the number of Sloboda Cossacks and their assistants had increased to 100,000 souls, and they already fielded 4,200 Cossacks for military service. To manage Sloboda Ukraine, Anna Ioannovna appointed a special office of guards officers, which was called the “Office of the Commission for the Establishment of Sloboda Regiments”. This board was hard and stupid, since the guards officers of the regular units had little to do with the Sloboda Cossacks. In addition, these officers were for the most part foreigners who hardly spoke Russian and who came to Russia at the call of their compatriot Biron to enrich themselves and seize Russian power.

In addition to increasing the outfit by almost 700 Cossacks, the entire male population of Sloboda Ukraine, not excluding the Cossacks, was taxed, contrary to the letters of the former kings, with significant annual monetary fees, the ranks of the Sloboda regiments were equated in service with the army and, moreover, the Cossacks were commanded for their account and maintenance to form the Dragoon Regiment, which was recruited from Slobozhan. In addition, many Slobozhans were enrolled in the so-called Landmilitsky regiments established by the government for the border service.

The accession to the Russian throne of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna brought relief to the Sloboda Cossacks both morally and especially materially. The new empress, listening to the advice of the all-powerful nobleman at the Court of Razumovsky, who came from a poor family of the Little Russian Cossack, canceled many of the hardships of the previous rule of foreigners. So, the Dragoon Regiment was ordered to immediately disband and cancel all monetary extortions from the Cossacks and assistants. In addition, with a special letter, the Empress solemnly confirmed all the previous rights and privileges of Slobozhan.

In 1760, the Sloboda Cossacks fielded 5,000 horsemen, divided, in the old way, into five regiments. At this time, the circumstances of their existence changed radically, thanks to the permission to settle on the Cossack lands to nonresident and alien people, as well as the formation of new peasant settlements south of Sloboda Ukraine. The Cossack territory was flooded with all sorts of raznochintsy, tenants of Cossack lands, buyers of all good things, and even private landowners who acquired land in eternity. All this led the Cossacks into a great decline, so that the masses of the Cossacks began to go into seasonal work and be hired as farm laborers to the landowners. The land became less and less every year, since there were many hunters for it from among the alien peasants who bought up the land. The settlements on the right of the Cossacks entered the service into unpaid debts and could hardly put up the necessary outfit.

In 1763, Catherine II instructed the Major of the Life Guards of the Izmailovsky Regiment, Yevdokim Shcherbinin, to head the "Commission on the Sloboda Regiments" in order to study the causes of "ill-being" in these lands in order to eliminate them. The result of the commission's activity was the proclamation by Catherine II on July 28, 1765 of the manifesto "On the establishment of a decent civil order in the Sloboda regiments and on the stay of the provincial and provincial office", according to which the Sloboda regiments were transformed into hussar ones, and the Sloboda-Ukrainian province with 5 provinces was founded on their territory. on the site of the former regiments and the administrative center in Kharkov. E. Shcherbinin was appointed the first Sloboda-Ukrainian governor.

All these orders were carried out in 1765, and after that time, the former Cossacks began to serve as regular soldiers, by recruitment, losing their Cossack rank and the privileges and advantages associated with it. However, many of the Sloboda Cossacks did not want to submit to the new order and partly went to the Don, the Urals and the Caucasus, partly joined the Cossacks living in Turkey. The current hussar regiments: Akhtyrsky, Sumy, Kharkov and Izyumsky are the successors of the old Sloboda Cossack regiments of the same name.

Sloboda

From 1780 to 1796, on the site of the Sloboda-Ukrainian province (without the Ostrogozhsk district), there was the Kharkov governorship. In 1796, the Sloboda-Ukrainian province was restored within the framework of the governorship with the addition of the Kupyansky district to it, and in 1835 it was abolished. In its place, the Kharkov province was created. At the same time, some border areas went to the Voronezh and Kursk provinces. Ethnic identity Having lost its autonomy, Slobozhanshchina retained many features of ethnic identity. Firstly, Ukrainian and Russian settlements interspersed here (often they were even nearby and had similar names, such as Russian Lozovaya and Cherkasskaya Lozovaya, Russian Tishki and Cherkasy Tishki). Secondly, the Ukrainian-Russian bilingualism, which resulted in a kind of Sloboda-Ukrainian dialect. Thirdly, the traditions of freedom-loving and free-thinking, coming from the Cossacks, who were free people in spirit and letter and had more rights and benefits, and, therefore, often more educated than the population of neighboring territories. It was here that in 1805 one of the first in Russia Kharkov Imperial University (the 6th in a row) arose. Therefore, many historians consider Slobozhanshchyna the cradle of the Ukrainian cultural revival (its creators are Skovoroda, Hulak-Artemovsky, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, and others).

Literature:

- Albovsky Evgeny. History of the Kharkov Sloboda Cossack Regiment 1650-1765. - Kharkov: Printing house of the provincial government, 1895. - 218 p. (13MB).

- Albovsky Evgeny. Kharkov Cossacks. Second half of the 17th century - History of the Kharkov regiment. - St. Petersburg., 1914. - T. 1. (26MB).

- Bagaley Dmitry. Materials for the history of colonization and life of Kharkov and partly Kursk and Voronezh provinces. - Kharkov: Type. K. L. Happy, 1890.- 456 p.

- "The sheet, from which cities and counties the Kharkov governorship was compiled and how many souls were in them for 1779." - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Gerbel N. Izyumsky Sloboda Cossack Regiment 1651-1765 - St. Petersburg, 1852.

- Lieutenant General and Cavalier Evdokim Shcherbinin. "Vedomosti for the Kharkov Viceroyalty on the matters below", December 1781. Part 5: "On contract wine to unprivileged cities and villages, and who are the suppliers to it." // Descriptions of the Kharkiv governorship of the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources / Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, Archaeological Commission, etc. / Compiled by: V. Pirko, A. Gurzhiy. Ed .: P. Sokhan, V. Smolii and others - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Lieutenant General and Cavalier Evdokim Shcherbinin. “Vedomosti on the Kharkiv governorship on the matters below”, December 1781. // Descriptions of the Kharkov governorship of the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Golovinsky P. Slobodsky Cossack regiments. - St. Petersburg: Type. N. Tiblen and Comp., 1864 on the Runivers website

- Dovidnik from the history of Ukraine.// Slobidska Ukraine. - Kiev "Geneza", 2002. Store. 776-778.

- Demoscope

- Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: historical chronicle. - Local history. - Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publishing House, 1989. - S. 72. - 100 p. - ISBN 5-7458-0076-3

- "Notes on Sloboda regiments" from the beginning of their settlement until 1766 "Kvitka G.F. Kharkov 1883 (reprint of the 1812 edition)

- The history of the settlement of the region. Melovatsky commissariat

- Kostomarov N.I. Autobiography. K: Naukova Dumka, 1991]

- Kulchitsky Stanislav, “Empire and us”, Den newspaper, 26 Jan. 2006

- "On the establishment of a decent civil order in the Sloboda regiments and on the stay of the provincial and provincial office." July 28, 1765

- Litvin V.M. National renewal in Slobozhanshchina. Gurtok of Kharkiv romantics

- Miloradovich M.A. Materials for the history of the Izyum Sloboda Regiment. - Kharkov, 1858.

- "Description of cities and noble towns in the provinces of the Sloboda province in 1767-1773". Provincial Chancellery, then archive of Kharkov Imperial University. In: “Kharkov collection. Literary and scientific supplement to the "Kharkov calendar" for 1887" Kharkov: 1887.

- Descriptions of the Kharkiv viceroy at the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources / Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, Archaeological Commission, etc. / Compiled by: V. Pirko, A. Gurzhiy. Ed .: P. Sokhan, V. Smolii and others - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- "Description of the cities of the Kharkov governorship". 1796. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- "Description of the city of Akhtyrka with the county." 1780. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Potebnya Alexander Afanasyevich // Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Potrashkov S.V. Kharkov regiments: Three centuries of history. - Kharkov: OKO, 1998. - 1500 eq.

- Saratov I. E. . The first coat of arms of the city of Kharkov. (Regimental period - until 1765). Journal of N&T No. 1-2008

- Saratov I. E. . Coats of arms of Kharkov during the Russian Empire (1781-1917). (Second, third, fourth emblems). N&T Journal No. 6-2008

- Saratov I.E. Kharkov, where does your name come from? / ed. N. Z. ALYABEV. - 3rd, supplemented. - X .: Publishing house HGAGH, type. Factor Druk, 2003. - S. 68-83. - 248 p. - (350th anniversary of Kharkov). - 415 copies. - ISBN no

- "List of the nobles of the Kharkov province for 1767".

- "Information about the change in the administrative-territorial division of the Voronezh region." Archival service of the Voronezh region

- Topographical description of the Kharkov governorship. - 3rd ed. (Kharkov, 1888). - M .: Printing house of the Printing Company, 1788. - S. 17.

- "Topographic description of the Voronezh vicegerency" of June 30, 1785

- Kharkov, 1941. Part one: At the edge of a thunderstorm / V. K. Vokhmyanin, A. I. Podoprigora. - Kharkov: Ryder, 2008. - 100 p. - (Kharkov in the war). - 1,000 copies. - ISBN 978-966-8246-92-0

Slobozhanshchina (Sloboda Ukraine) is a historical region that was part of the Russian state of the 17th-18th centuries (the territory of modern Kharkov, as well as parts of the Sumy, Donetsk, Lugansk regions of Ukraine, Belgorod, Kursk and Voronezh regions of Russia).

origin of name

Slobozhanschina in 1667-1687

The word "sloboda", according to the "Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language" by V.I. Dalia means "village of free people". This is where the names Sloboda Ukraine and Sloboda Ukraine come from. Now it is a territory covering most of Kharkov, east of Sumy, north of Lugansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine and border regions of Belgorod, Kursk and Voronezh regions of the Russian Federation.

Heiress of the Wild Field

Traces of the oldest settlement of Slobozhanshchina come from the early Paleolithic. At first, Slobozhanshchina was part of the territory of the northerners, from the end of the 9th century it became part of the Kyiv state, in the 11th century. to Chernigov, and later Pereyaslav and Novgorod-Seversk principalities. After the Tatar-Mongol invasion of the XIII century. the region is empty. From the beginning of the XVI century. Slobozhanshchina becomes part of the Moscow Principality. The territory of Slobozhanshchina was by that time almost uninhabited Wild Field, through which the Tatars raided deep into the Muscovite state - of course, along the Muravsky Way (he led the watershed between the Dnieper and Don - from Perekop to Tula), as well as its branch - the Izyumsky and Kalmiussky Ways On Slobozhanshchina deep into the steppe went Ukrainian industrialists - "goers", "dobichnikiv", who were mainly engaged in beekeeping, fishing and hunting, as well as the extraction of saltpeter and salt (on the Torsk lakes and in Bakhmut).

Exploration of the Wild Field

Sloboda Ukraine in the XVII-XVIII centuries. - until 1765

From the second half of the 16th century, refugees began to move from Ukraine-Rus, which was then under Poland, to the east, in areas that were considered the territory of Russia. They left, fleeing the Polish-Catholic aggression, not only a few, or individual families, but entire groups, often several hundred people or even several hundred families. Moscow willingly accepted them and helped in every possible way to settle in a new place, giving out help in kind and money, and allocating good land for settlement. They settled in the then deserted, richest lands, within the pre-revolutionary Kharkov province and adjacent counties of the Voronezh and Kursk provinces. These lands were to the south behind the row of border fortresses created by Moscow against the raids of the Tatars, the so-called "Belgorod line", which stretched (from west to east) from Akhtyrka, through Korocha and Novy Oskol, to Ostrogozhsk and rested on the upper reaches of the Don. The possibility and likelihood of Tatar raids, which during their attacks on Moscow usually passed through these lands, forced the new settlers to organize to repel these raids, creating, following the model of the Hetmanate, Cossack regiments and hundreds. Moscow, for carrying out this military service and guarding the borders, freed the new settlers from all taxes and duties and helped them with weapons and ammunition.

In 1732, these regiments were renamed into dragoon regiments, but this reform caused discontent among the suburban Cossacks, who valued the old traditions of the Cossacks, and therefore, with the accession of Empress Elizabeth, who favored the Ukrainians, in 1743, these regiments were again turned into Cossack ones. Only in 1764, after the abolition of the hetmanship on the Left Bank, the suburban Cossack regiments were finally turned into hussar regiments of the regular cavalry of the Russian army. The foremen of these regiments turned into hereditary nobles of the Russian Empire, like the Cossack foreman of the Left Bank.

The social structure of Sloboda

Russian empire

The social structure of Sloboda Ukraine basically changed in the same way as on the Left Bank. The refugee mass that arrived from Ukraine-Rus was homogeneous and free. With the organization of military units (for the protection of the southern borders), a foreman stands out from this mass - a privileged group. The rest of the mass, in the process of further administrative and military organization of Slobozhanshchina, is divided into Cossacks and free settlers. Gradually, a number of obligations are imposed on the free settlers. First, in relation to the foreman, and then, in relation to other layers of the Cossacks, with their transformation into the so-called "state peasants". descendants, or, “granted” by the Russian empresses to individuals. This is how landowners were created in Sloboda Ukraine. The urban population of Slobozhanshchina was extremely small, because the young, recently founded cities were also small. It consisted of persons involved in the administrative apparatus (military, officials), the clergy, merchants and artisans. Unlike the Left Bank, where the urban population was exclusively from the local population, there were many Great Russians in the cities of Sloboda Ukraine. There were no Jews in Sloboda Ukraine then.

In the field of cultural life of the population, Sloboda Ukraine, which was initially busy with organizing life in new places, did not show itself in anything special and did not create any cultural centers, monasteries or well-known schools. They were content with what came either from the Dnieper region or from Great Russia, constructively combining both influences and gradually merging with the all-Russian cultural life. The separatists call this process “forced Russification.” But they do not cite any evidence of “violence” and hush up that the question is about the cultural life of the refugees who moved to Great Russia (the Muscovite kingdom), that is, to another, at that time, state. And, of course, it is natural that the Moscow governors and service people who were in the territory where the refugees settled were in no hurry to adopt their language and way of life from the refugees.

The “Moscow people” did not interfere at all with the everyday side of life, the customs, the customs of the settlers, without preventing them from maintaining their way of life, the cut of clothes, forelocks, mustaches and “settlers”, without forcing them to let go of their beards in the Moscow fashion, but they did not shave their beards either. and forelocks were not released to please the settlers. In the cultural field, there is also no evidence of "violence" or the forced use of the "Moscow" (Great Russian) language. Each of them spoke with the settlers in their own language and, to the general joy,

made sure they understood each other perfectly. The trial (without any interpreters) was carried out on the basis of Moscow laws, binding on the entire territory of the Muscovite kingdom, including the lands provided for settlement by refugees from the Dnieper region.

The separatists see “forced Russification” in this, completely forgetting the fact that nowhere and never, immigrants to another country, do not organize their court according to their own laws, but obey the laws of the country that adopted them. As a result of all social processes, administrative measures and joint life with the Great Russians, by the end of the 18th century, Sloboda Ukraine was firmly merging with the rest of Russia, while maintaining its Ukrainian domestic and national characteristics.The organization of the national economy in Sloboda Ukraine was similar to that in the Hetmanate. agriculture and related cattle breeding. The dominant system of agriculture was variable; in the second half of the 18th century, a three-field system also began to spread. In addition to Cossack and peasant small land ownership, high society (Cossack elders and Russian nobility, as well as monasteries) possessions developed, sometimes reaching the size of latifundia.

A significant place in Sloboda Ukraine was occupied by sheep breeding (in the 13th century, also fine-wooled), beekeeping, gardening, fishing, milling, distilling, dektyarstvo) and various crafts and handicrafts (at the end of the 18th century, about 34,000 artisans and handicraftsmen were recruited in Sloboda Ukraine ). A prominent place was occupied by the salt industry (Torsk, Bakhmut and Spivakovsky plants).

In the XVIII century. manufactories appear, in particular the Chuguevskaya leather manufactory of F. Shidlovsky (born in 1711), the official tobacco one in Akhtyrka (1719), the Saltovskaya cloth Count Gendrikov (1739), and the linen centurion. Akhtyrsky regiment of Semen Nakhimov (1769), silk factories in the city of Novaya Vodolaga (end of the 18th century), etc. The cells of trade were fairs, of which there were 271 in 1779, mostly of a local nature, barely 10 medium and only 2 large - in Sumy and Kharkov. Of great importance was the transit trade through Sloboda Ukraine, which became an intermediary in trade between Russia, on the one hand, and the Hetmanate, Zaporozhye and Southern Ukraine, Crimea and the Don, the Caucasus and Iran, on the other. In particular, lively trade relations were between Sloboda Ukraine and the Hetmanate. Salt from the Torsky and Bakhmut salt works went from Sloboda Ukraine to the Hetmanate, industrial products, in particular glass, ironmongery, potash, vodka, etc., went from the Hetmanate to Sloboda Ukraine.

The political life of Sloboda Ukraine was limited by the Moscow state, and later by the Russian Empire, of which, although semi-autonomous, it was a part. But already the geographical position of Sloboda Ukraine between Moscow and the Crimean Khanate, Moscow and the Don, and especially Moscow and the Hetmanate more than once drew Sloboda Ukraine into the contradictions of the Eastern politics of that time. Sloboda Ukraine was the territory of devastating Tatar attacks from the south, which continued until the Russian-Turkish war of 1769–74 and the Kuchuk-Kainarji peace treaty of 1774. Sloboda Ukraine suffered great destruction (especially its western part – Sumy and Okhtyrshchyna), when in the winter the hostilities of the Swedish and Moscow troops spread to Sloboda Ukraine, which Charles XII considered as enemy territory. The Russian-Turkish war of 1735-39 also brought great damage to the economy of Sloboda Ukraine. conflicts between Sloboda Ukraine and the Moscow government, and sometimes caused riots and even uprisings of Sloboda residents against Moscow. In 1670, an uprising broke out in the Ostrogozhsky regiment, associated with the war led by Stepan Razin. The uprising, which was led by the old colonel Ivan Dzikovsky. It was soon suppressed, and Dzikovsky and his wife Evdokia, along with most of the rebels who were captured, were executed. The population of Sloboda Ukraine also took part in the K. Bulavin uprising of 1707-08, but the Sloboda regiments, together with some regiments of the Hetmanate, were forced to help Moscow pacify the uprising.

When in 1711 the Crimean Khan Devlet-Girey attacked Sloboda Ukraine (the Tatars then destroyed Bakhmut, captured Zmiev, Staraya Vodolaga and Merefa and devastated the regions of Izyum and Kharkov), the population of both Vodolagas, led by a foreman, joined the Tatars, for which Peter I ordered " execute the tenth by lot, and send all the rest with their wives and children to Moscow for exile. The Gaidamak uprisings in the Right-Bank Ukraine also had reviews in Sloboda Ukraine, but here they had a predominantly social (and then local) character.

Loss of autonomy

Reunification of Ukraine with Russia

The Sloboda regiments faithfully carried out, often very difficult, border service and participated in many campaigns and battles of the Russian army, distinguished by exemplary courage and stamina, for which they often received the approval of the highest authorities. In the battle of Gross-Egersdorf in the Prussian war, the Sloboda regiments rushed into a desperate attack on the Prussians and, falling under fierce grapeshot fire, suffered heavy losses in people and horses, but with this attack the Cossacks greatly helped the success of Russian weapons and once again testified to their hereditary courage.

The Sloboda Cossacks fought just as bravely and selflessly even earlier, near Azov, being among the tsarist troops, for which they were praised by Tsar Peter the Great himself, who, for Cossack merits, ordered in 1700 to release the “assistants” from paying a special tax to the treasury of the state. 1 ruble per year from the soul and determined the annual set of Sloboda regiments at 3,500 Cossacks. The Cossack service at that time was difficult and dangerous, the Cossacks received almost no salary and assistance from the government, but, despite these unfavorable conditions for the farmer, the Cossacks valued their knightly name more than anything else and faithfully kept the oath given to the king. For the loyalty and courage of the Sloboda Cossacks, Peter the Great granted them a letter confirming all their former rights and privileges.

Peter the Great, in the transformations of the whole of Russian life in general, did not leave Slobozhan alone either, ordering that the regiments be subordinated to the management of the Military Collegium and to direct command, appointing a special regular commander, who was given the right to promote the regimental foreman to the ranks and perform the functions of a military ataman, in however, on a very limited scale.

In 1731, the so-called Ukrainian line was arranged, the purpose of which was to serve as an obstacle to the invasion of the Russian borders of the Tatar gangs. According to the arrangement of this line, there was a need for huge excavation work on the embankment, the construction of trenches at individual forts and pickets. All this work was carried out by the Little Russian and Sloboda Cossacks appointed for this purpose, thus protecting peaceful Russian landowners from Tatar robberies. The reign of Anna Ioannovna was a difficult era for the Sloboda Cossacks, who for some reason did not like the proud and all-powerful German Biron at the Court.

By 1735, the number of Sloboda Cossacks and their assistants had increased to 100,000 souls, and they already fielded 4,200 Cossacks for military service. To manage Sloboda Ukraine, Anna Ioannovna appointed a special office of guards officers, which was called the “Office of the Commission for the Establishment of Sloboda Regiments”. This board was hard and stupid, since the guards officers of the regular units had little to do with the Sloboda Cossacks. In addition, these officers were for the most part foreigners who hardly spoke Russian and who came to Russia at the call of their compatriot Biron to enrich themselves and seize Russian power.

In addition to increasing the outfit by almost 700 Cossacks, the entire male population of Sloboda Ukraine, not excluding the Cossacks, was taxed, contrary to the letters of the former kings, with significant annual monetary fees, the ranks of the Sloboda regiments were equated in service with the army and, moreover, the Cossacks were commanded for their account and maintenance to form the Dragoon Regiment, which was recruited from Slobozhan. In addition, many Slobozhans were enrolled in the so-called Landmilitsky regiments established by the government for the border service.

The accession to the Russian throne of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna brought relief to the Sloboda Cossacks both morally and especially materially. The new empress, listening to the advice of the all-powerful nobleman at the Court of Razumovsky, who came from a poor family of the Little Russian Cossack, canceled many of the hardships of the previous rule of foreigners. So, the Dragoon Regiment was ordered to immediately disband and cancel all monetary extortions from the Cossacks and assistants. In addition, with a special letter, the Empress solemnly confirmed all the previous rights and privileges of Slobozhan.

In 1760, the Sloboda Cossacks fielded 5,000 horsemen, divided, in the old way, into five regiments. At this time, the circumstances of their existence changed radically, thanks to the permission to settle on the Cossack lands to nonresident and alien people, as well as the formation of new peasant settlements south of Sloboda Ukraine. The Cossack territory was flooded with all sorts of raznochintsy, tenants of Cossack lands, buyers of all good things, and even private landowners who acquired land in eternity. All this led the Cossacks into a great decline, so that the masses of the Cossacks began to go into seasonal work and be hired as farm laborers to the landowners. The land became less and less every year, since there were many hunters for it from among the alien peasants who bought up the land. The settlements on the right of the Cossacks entered the service into unpaid debts and could hardly put up the necessary outfit.

In 1763, Catherine II instructed the Major of the Life Guards of the Izmailovsky Regiment, Yevdokim Shcherbinin, to head the "Commission on the Sloboda Regiments" in order to study the causes of "ill-being" in these lands in order to eliminate them. The result of the commission's activity was the proclamation by Catherine II on July 28, 1765 of the manifesto "On the establishment of a decent civil order in the Sloboda regiments and on the stay of the provincial and provincial office", according to which the Sloboda regiments were transformed into hussar ones, and the Sloboda-Ukrainian province with 5 provinces was founded on their territory. on the site of the former regiments and the administrative center in Kharkov. E. Shcherbinin was appointed the first Sloboda-Ukrainian governor.

All these orders were carried out in 1765, and after that time, the former Cossacks began to serve as regular soldiers, by recruitment, losing their Cossack rank and the privileges and advantages associated with it. However, many of the Sloboda Cossacks did not want to submit to the new order and partly went to the Don, the Urals and the Caucasus, partly joined the Cossacks living in Turkey. The current hussar regiments: Akhtyrsky, Sumy, Kharkov and Izyumsky are the successors of the old Sloboda Cossack regiments of the same name.

Sloboda

From 1780 to 1796, on the site of the Sloboda-Ukrainian province (without the Ostrogozhsk district), there was the Kharkov governorship. In 1796, the Sloboda-Ukrainian province was restored within the framework of the governorship with the addition of the Kupyansky district to it, and in 1835 it was abolished. In its place, the Kharkov province was created. At the same time, some border areas went to the Voronezh and Kursk provinces. Ethnic identity Having lost its autonomy, Slobozhanshchina retained many features of ethnic identity. Firstly, Ukrainian and Russian settlements interspersed here (often they were even nearby and had similar names, such as Russian Lozovaya and Cherkasskaya Lozovaya, Russian Tishki and Cherkasy Tishki). Secondly, the Ukrainian-Russian bilingualism, which resulted in a kind of Sloboda-Ukrainian dialect. Thirdly, the traditions of freedom-loving and free-thinking, coming from the Cossacks, who were free people in spirit and letter and had more rights and benefits, and, therefore, often more educated than the population of neighboring territories. It was here that in 1805 one of the first in Russia Kharkov Imperial University (the 6th in a row) arose. Therefore, many historians consider Slobozhanshchyna the cradle of the Ukrainian cultural revival (its creators are Skovoroda, Hulak-Artemovsky, Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, and others).

Literature:

- Albovsky Evgeny. History of the Kharkov Sloboda Cossack Regiment 1650-1765. - Kharkov: Printing house of the provincial government, 1895. - 218 p. (13MB).

- Albovsky Evgeny. Kharkov Cossacks. Second half of the 17th century - History of the Kharkov regiment. - St. Petersburg., 1914. - T. 1. (26MB).

- Bagaley Dmitry. Materials for the history of colonization and life of Kharkov and partly Kursk and Voronezh provinces. - Kharkov: Type. K. L. Happy, 1890. - 456 p.

- "The sheet, from which cities and counties the Kharkov governorship was compiled and how many souls were in them for 1779." - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Gerbel N. Izyumsky Sloboda Cossack Regiment 1651-1765 - St. Petersburg, 1852.

- Lieutenant General and Cavalier Evdokim Shcherbinin. "Vedomosti for the Kharkov Viceroyalty on the matters below", December 1781. Part 5: "On contract wine to unprivileged cities and villages, and who are the suppliers to it." // Descriptions of the Kharkiv governorship of the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources / Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, Archaeological Commission, etc. / Compiled by: V. Pirko, A. Gurzhiy. Ed .: P. Sokhan, V. Smolii and others - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Lieutenant General and Cavalier Evdokim Shcherbinin. “Vedomosti on the Kharkiv governorship on the matters below”, December 1781. // Descriptions of the Kharkov governorship of the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Golovinsky P. Slobodsky Cossack regiments. - St. Petersburg: Type. N. Tiblen and Comp., 1864 on the Runivers website

- Dovidnik from the history of Ukraine.// Slobidska Ukraine. - Kiev "Geneza", 2002. Stor. 776-778.

- Demoscope

- Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: historical chronicle. - Local history. - Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publishing House, 1989. - S. 72. - 100 p. — ISBN 5-7458-0076-3

- "Notes on Sloboda regiments" from the beginning of their settlement until 1766 "Kvitka G.F. Kharkov 1883 (reprint of the 1812 edition)

- The history of the settlement of the region. Melovatsky commissariat

- Kostomarov N.I. Autobiography. K: Naukova Dumka, 1991]

- Kulchitsky Stanislav, “Empire and us”, Den newspaper, 26 Jan. 2006

- "On the establishment of a decent civil order in the Sloboda regiments and on the stay of the provincial and provincial office." July 28, 1765

- Litvin V.M. National renewal in Slobozhanshchina. Gurtok of Kharkiv romantics

- Miloradovich M.A. Materials for the history of the Izyum Sloboda Regiment. - Kharkov, 1858.

- "Description of cities and noble towns in the provinces of the Sloboda province in 1767-1773". Provincial Chancellery, then archive of Kharkov Imperial University. In: “Kharkov collection. Literary and scientific supplement to the "Kharkov calendar" for 1887" Kharkov: 1887.

- Descriptions of the Kharkiv viceroy at the end of the 18th century: Descriptive and statistical sources / Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, Archaeological Commission, etc. / Compiled by: V. Pirko, A. Gurzhiy. Ed .: P. Sokhan, V. Smolii and others - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. - ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- "Description of the cities of the Kharkov governorship". 1796. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- "Description of the city of Akhtyrka with the county." 1780. - K .: Naukova Dumka, 1991. ISBN 5-12-002041-0

- Potebnya Alexander Afanasyevich // Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Potrashkov S.V. Kharkov regiments: Three centuries of history. - Kharkov: OKO, 1998. - 1500 eq.

- Saratov I. E. . The first coat of arms of the city of Kharkov. (Regimental period - until 1765). Journal of N&T No. 1-2008

- Saratov I. E. . Coats of arms of Kharkov during the Russian Empire (1781-1917). (Second, third, fourth emblems). N&T Journal No. 6-2008

- Saratov I.E. Kharkov, where does your name come from? / ed. N. Z. ALYABEV. — 3rd, supplemented. — H.: Publishing house HGAGH, type. Factor Druk, 2003. - S. 68-83. — 248 p. - (to the 350th anniversary of Kharkov). - 415 copies. - ISBN no

- "List of the nobles of the Kharkov province for 1767".

- "Information about the change in the administrative-territorial division of the Voronezh region." Archival service of the Voronezh region

- Topographical description of the Kharkov governorship. - 3rd ed. (Kharkov, 1888). - M .: Printing house of the Printing Company, 1788. - P. 17.

- "Topographic description of the Voronezh vicegerency" of June 30, 1785

- Kharkov, 1941. Part one: At the edge of a thunderstorm / V. K. Vokhmyanin, A. I. Podoprigora. - Kharkov: Ryder, 2008. - 100 p. - (Kharkov in the war). — 1,000 copies. — ISBN 978-966-8246-92-0

Sloboda Ukraineis one of the parts of Ukraine. Interestingly, our Kharkov Ukrainian philosopher Grigory Savvich Skovoroda called the Left-Bank Ukraine, or, as he said, "Little Russia", his mother, and Sloboda Ukraine - his own aunt, because here he lived and loved this region, as his biographer M. AND. Kovalinsky. It turns out that at the end of the 18th century, when Skovoroda lived, after the liquidation of the autonomous system of the Hetmanate (so once called the Left-Bank Ukraine , note Bagalei) and Sloboda Ukraine, the name "Ukraine" referred specifically to the so-called "Wild Field". And indeed, this land is more, tender ate other parts of the Ukrainian land, must was so be nicknamed in the territorial sense of the word, since it was "Ukraine", that is, the outskirts, Russian-Ukrainian lands. Once a Russian chronicler called Ukraine the Russian borderlands Pereyaslav land with Polovtsian steppes; and there and here, in addition to the ethnographic, the geographical meaning of this word is felt. For every inhabitant of the Dnieper Right Bank, and even Left Bank, the then "wild field", which was subsequently settled by Ukrainian settlers with their settlements and which earlier, in the pre-Mongolian period, in the XI- XIII Art. was inhabited by the great-grandfathers of the Slobozhans - the ancient Russians of the Chernihiv-Pereyaslav land, although it was the ancestral home of the Ukrainians of the 17th century, but distant ukraine. Sloboda Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century occupied almost the entire Kharkov province and some of the counties of Kursk and Voronezh provinces.

It was a plain, on which small hills stretched here and there. Above the rest was the northern part of the Kharkiv region, and to the south it became lower and lower until it reached the spurs of the Donetsk stingy mountains. The Kursk province was the most elevated in comparison with the neighboring Kharkov and Voronezh, but even there there are only tie mountains. The watershed of the Dnieper and Don water basins passed along them, where the Muravsky Way, famous in the history of the region, ran.. And already from this watershed, hollows with gullies and ravines diverged to the west, where there were many rivers and streams.

The local rivers had a significant impact on the settlement of the "wild field". Now none of them is navigable, but once it was different. By Donets Seversky numerous punts with bread were rafted from Belgorod to Chuguev, and from there they went to the Don. According to Oskol at the end of the XVI century. Moscow service people sailed to its mouth with all sorts of supplies for the construction of the city of Tsareborisov. Dnieper tributaries - Psel, Sula, Vorskla - connected Sloboda Ukraine with Poltava region; the river Vyr, which flows into the Seim, and that into the Desna, made it possible to communicate with the Chernihiv region. On the territory of Slobozhanshchina, the Dnieper rivers approached the Don ones. Slobozhans first began to settle where there was more water. That is why the western sections of the region were settled more densely and earlier than the eastern ones, since there were fewer rivers in the east. But from the 18th century Slobozhansky rivers begin to shallow from year to year, because the number of forests has greatly decreased, and they have thinned out.

All the most important and oldest cities and settlements were based on rivers:

The Wild Field got its name because it was covered with steppes interspersed with forests. It is not surprising that the steppes from time immemorial attracted hordes of nomadic tribes (Huns, Avars, Pechenegs, Torks, Kumans, Tatars). The memory of this is kept by geographical names: the village of Pechenegy, the river Torka, etc. It was not easy for a settler who settled in Ukraine to find a Polovtsian or a Tatar in the yogi nomad camps: look for wind in the field. And the Tatar, on the contrary, suddenly flew into villages and farms, killed and led away into a full of Slobozhans, robbed cattle and goods. Slobozhans were forced to defend themselves from the Tatar raids through forests, swamps, mountains, high graves, settlements, earthen ramparts, wooden fences, fences ... Consequently, the steppe was not an obstacle to the settlement of settled people, but at the same time did not protect them from the Tatar. Another thing is the forest. It slightly slowed down the settlement process, but at the same time served as protection for the settlers from enemy attacks. There were more forests then than there are now. Forests and meadows alternated along the entire coast of the Donets from Oskol to Zmiyov, along the tributaries of the Donets there were also dense forests, sometimes along both banks: Izyumsky, Teplinsky, Cherkassky, etc. The forest was a real treasure for the Slobozhans, because both fortresses and castles were made from it, as well as everything that was needed in the economy, in particular budi, guti, burti, wind and water mills, as well as distilleries. For the lastmost of all, forests were exhausted, since then every Ukrainian had the right to drive vodka.

Nature generously endowed Slobozhanshchina with fruit trees and shrubs, most often the first settlements - farms of the region - were gardens with apiaries. The region was rich in wild animals: bison, bears, wolves, elks, wild boars, many fur-bearing animals (sables, foxes, martens, beavers, otters, etc.) lived in the forests; in the steppes - saigas and wild horses. There were also many wild birds - partridges, quails, snipes, woodcocks, bustards, black grouses, ducks, swans, cranes, little bustards, falcons, gyrfalcons, hawks, eagles. It is not surprising that fishing was widespread in this region, there were even "king's catches" here - something like reserves for royal hunting. There were countless fish in the rivers. Minerals were not enough, only there was plenty of salt, it was mined on the Torsky and Mayatsky lakes, and then the Chumaks were transported everywhere. They also mined stone for millstones, chalk, which went to huts-huts, pottery clay. Thus, this region was able to provide the Slobozhans with a cultural life full of prosperity. Chernozem soil prevailed, the virgin land was very fertile. In Chuguev, in addition to chestnut trees with watermelons and melons, even vineyards were planted for the Moscow tsars. In the wide steppes it was easy to breed herds of horses, flocks of sheep, herds of bulls, cows and calves. The climate was not severe - the air remained warm in spring, summer and autumn.

Svatovsky District Cossack Society of Ukrainian Cossacks

"Svatovsky Sloboda Regiment"

Matchmaking - Cossack land

A historical and local history essay dedicated to the 500th anniversary of the emergence of Ukrainian Cossack settlements on the territory of Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Svatovo, 2006

11. Cancellation of Cossack autonomy and privileges in Slobozhanshchina.

During the frequent raids of the Crimean and Nogai hordes, the Moscow government was forced to endure the Cossack autonomy that had developed in Slobozhanshchina and those diverse privileges that had previously been granted, and when the threat of attack from the Tatars and Turks in the south was significantly reduced, the government began to systematically limit the Cossack autonomous way of life and liquidate former privileges.

In 1700, Peter I issued a letter in which he actually abolished the suffrage of the Sloboda Cossacks. Since that time, the colonels of the Sloboda Cossack regiments began to be appointed by the tsarist government, and they had to remain with their governments until their death. The entire Cossack foreman began to be appointed for life. The same charter limited the number of Sloboda Cossacks to 3,500 people.

Since 1706, a number of measures were taken by the government to break the old woman and strengthen the new system of government in the Sloboda region. Royal decree of 1706r. the voivodeship administration in the Sloboda regiments was abolished and the sole power was concentrated in the hands of the colonels, who were given the military rank of prime minister of the Russian army. At the same time, the Ukrainian division was formed, which, along with the Cossack regiments of the Left Bank, also included the regiments of Sloboda Ukraine. Thus, militarily, the Sloboda regiments were recruited and maintained in the old way, but organizationally they already constituted an integral part of the only Russian army. At the head of all five regiments was a brigadier, who, in military affairs, was subject to the general - commander of the Ukrainian division. In connection with the division of Russia into provinces, in 1708r. Slobiska Ukraine was administratively included in the Azov province, and from 1718 - in the Kyiv province.

However, in judicial and criminal cases, Slobozhanshchina remained under the jurisdiction of the Belgorod and Voronez provincial offices.

By a royal decree of September 4, 1722, the Sloboda regiments were excluded from the Kyiv province. The Cossacks of Slobozhanshchina were given the right to complain about any harassment of the foremen and incorrect decisions of the regimental town halls to the Belgorod table, and about the abuse of the voivode himself - to the Kursk Court Court.

When the inevitable war between Russia and Turkey for access to the Black Sea was brewing, the government of Catherine I found it expedient to strengthen the administration of the central government in Slobozhanshchina, and in 1726, by decision of the Supreme Secret Rada, the Sloboda regiments were transferred to the jurisdiction of the Military Collegium, although they were still directly subject to the commander Ukrainian division.

In 1729, the destruction of the Cossack recruiting system for the Sloboda regiments began. In the Izyumsky regiment there was an educated regular company of 100 people under the command of a regimental captain appointed commander of the Ukrainian division. The following year, the same company was formed in the Okhtirsky regiment, and a year later - in the Sumy and Kharkov regiments. These companies were recruited from local peasants, who were counted for permanent service. Their content relied on the local population - the so-called properties and assistants. From these regular companies was created the Sloboda Dragoon Regiment.

Under Queen Annie in 1732 - 1737. there was a reform of the Sloboda regiments, during which local autonomy was completely broken, and all Cossack rights and privileges were taken away. The reform began from the census of the Sloboda regiments, which was made by the Life Guards Major Khrushchov in 1732. Dispossessed by the constant army drill, various Cossack uniforms and duties, the Sloboda Cossacks abandoned their regiments and lands during the transfer and moved on to the state of assistants and pospolitov. And therefore, the queen instructs Prince Shakhovsky to go to Slobozhanshchina in the city of Sumy and create there the “Office of the Commission for the Establishment of Sloboda Regiments”, which was supposed to develop and implement such reforms in Sloboda Ukraine that would preserve the interests of the government and Sloboda residents.

In accordance with these reforms, all the Sloboda regiments were withdrawn from the subordination of the Military Collegium and subordinated to the established “Chancery of the Commission for the Establishment of the Sloboda Regiments”. The personnel of the regiments was determined: in the Okhtirsky regiment there should have been 1000 people, in all others - 800 people each, and only 4200 Cossacks. From their children and brothers-in-law, registered Cossacks were recruited, of which there were 22,000 chols. They also had to contribute 10 kopecks. from the soul to the Cossacks. 86,000 Cossack assistants and pіdsusіdkіv was divided into yards of 50 people. in each, and each yard had to pay 1 portion and 2 portions, and as money, then 18 kopecks. from the soul. Of all those recorded at the census, Khrushchov was ordered to collect 21 kopecks. to the treasury.

Regimental town halls were renamed into regimental offices and were compared to the offices of the provinces of the Russian provinces. The regimental office included a colonel, a baggage officer, a judge, a captain, a captain and clerks.

The reform was the abolition of the ancient right to borrow land, and henceforth the regiments were forbidden to occupy the so-called free land. All court cases in the regiments were now considered on the basis of the Code of Laws of the Russian State and following government decrees. Thus, the reform of 1732-1737, while maintaining the formal existence of the Sloboda regiments, actually turned them into parts of the Russian army, and the regimental offices into ordinary state bodies of the provinces.

Thousands of Sloboda residents dispersed from heavy odbutkіv from their places, fled to the Don, to the Hetmanate or Russia. Fearing that Slobozhanshchina will become completely depopulated, the government issues decrees on the search for beggars from the Sloboda regiments of Cossacks and common people with women and children in the provinces and provinces and their return to their former homes on carts and at the expense of those who accepted them.

Soon, all the reforms of Queen Annie were canceled by her successor Lizaveta, who was generally against Annie. At the end of 1743, the Sloboda Cossacks were given letters of commendation, in which all Annie's reforms were canceled, and the Cossacks got back their ancient rights and privileges in crafts and trade. Assistants were selected from the officers and foremen of the dragoon regiment and returned to the Sloboda regiments. The dragoons were abolished and turned back into the Cossacks. But the Sloboda residents still had to keep four army regiments. The number of elected Cossacks is definitely 5000 people. Soon the number of Cossacks was increased to 7500 chols.

On October 30, 1743, the “Office of the Commission for the Establishment of the Sloboda Regiments” was canceled and the Sloboda Regiments were again ordered by the Military Collegium. In all regimental cities the governor had his commissars. Militarily, the regiments were subsequently led by a brigadier, subordinate to the commander of the Ukrainian division.

While making some concessions, the government of Elizabeth at the same time did not weaken the autocratic power, the feudal lord, in Slobozhanshchina. The Cossacks of all five of the Sloboda regiments were dressed in uniforms. In 1746, a regular Sloboda hussar regiment was formed, similar to the dragoon one. Bagaliy writes: “People ran away from this hussar; ordinary people sometimes beat those hussars, and the foreman did not stop him in these actions, because she herself was at enmity against them.

By decrees of July 28, 1748 and February 24, 1749, Cossacks and their assistants were forbidden to move not only to the Hetmanate and Russia, but even from one regiment to another. Thus, the Cossacks and assistants were attached to their regiments forever.