Social movement in Russia in the second half of the 19th century. Development of the radical movement in Russia in the 19th century

Read also

I. Socio-political development of Russia in the first half of the 19th century. Choosing the path of social development

1. Social movements in Russia in the first quarter of the 19th century.

2. Decembrist movement.

3. Social movements in Russia in the second quarter of the 19th century.

4. National liberation movements

II. Socio-political development of Russia in the second half of the 19th century.

1. Peasant movement

2. Liberal movement

3. Social movement

4. Polish uprising of 1863

5. Labor movement

6. Revolutionary movement in the 80s - early 90s.

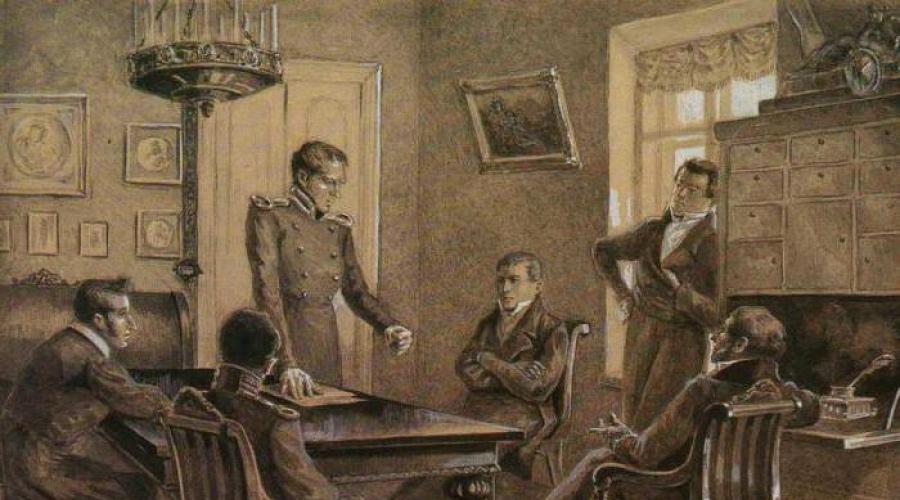

Decembrist movement

The government’s refusal of the policy of transformation and the strengthening of the reaction caused the emergence of the first revolutionary movement in Russia, the basis of which was made up of progressive-minded military men from the liberal strata of the nobility. One of the origins of the emergence of “freethinking in Russia” was Domestic

war

.

In 1814-1815 The first secret officer organizations emerge (“Union of Russian Knights”, “Sacred Artel”, “Semyonovskaya Artel”). Their founders - M. F. Orlov, M. A. Dmitriev-Mamonov, A. and M. Muravyov - considered it unacceptable to maintain the serfdom of peasants and soldiers who committed a civil feat during the Napoleonic invasion.

IN

February

1816

G

.

in St. Petersburg, on the initiative of A. N. Muravyov, N. M. Muravyov, M. and S. Muravyov-Apostolov, S. P. Trubetskoy and I. D. Yakushkin Union

salvation

.

This centralized conspiracy organization included 30 patriotic young military men. A year later, the Union adopted a “statute” - a program and charter, after which the organization began to be called Society

true

And

"

faithful

sons

Fatherland

.

The goals of the struggle were declared to be the abolition of serfdom" and the establishment of constitutional government. These demands were supposed to be presented at the time of the change of monarchs on the throne. M. S. Lunin and I. D. Yakushkin raised the question of the need for regicide, but N. Muravyov, I. G. Burtsov and others opposed violence and advocated propaganda as the only method of action.

Disputes about ways to achieve the society's goals necessitated the adoption of a new charter and program. In 1818, a special commission (S.P. Trubetskoy, N. Muravyov, P.P. Koloshin) developed a new charter, called the “Green Book” after the color of the binding. The first secret society was liquidated and created Union

prosperity

.

Members of the Union, who could become not only military men, but also merchants, townspeople, clergy and free peasants, were given the task of preparing public opinion to the need for change. Ultimate goals Union - a political and social revolution - was not declared in the “Book”, since it was intended for wide distribution.

The Welfare Union had about 200 members. It was led by the Root Council in St. Petersburg, the main councils (branches) were located in Moscow and Tulchin (in Ukraine), councils arose in Poltava, Tambov, Kyiv, Chisinau, and in the Nizhny Novgorod province. Educational societies of a semi-legal nature were formed around the Union. Officers - members of society - put the ideas of the “Green Book” into practice (abolition of corporal punishment, training in schools, in the army).

However, dissatisfaction with educational activities in the context of growing peasant unrest, protests in the army, and a number of military revolutions in Europe led to the radicalization of part of the Union. In January 1821, a congress of the Root Council met in Moscow. He declared the Welfare Union “dissolved” to facilitate the weeding out of “unreliable” members who opposed the conspiracy and violent measures. Immediately after the congress, the secret Northern and Southern societies arose almost simultaneously, uniting supporters of the armed coup and preparing the uprising of 1825.

Southern

society became the Southern Administration of the Union of Welfare in Tulchin. Its chairman became P

.

AND

.

Pestel(1793-1826). He was a man of enormous talents, received an excellent education, distinguished himself in the battles of Leipzig and Troyes. By 1820, Pestel was already a staunch supporter of the republican form of government. In 1824, the Southern Society adopted the program document he compiled - “Russian

The truth"

,

put forward the task of establishing a republican system in Russia. “Russian Truth” proclaimed the dictatorship of the Provisional Supreme Government for the entire duration of the revolution, which, as Pestel assumed, would last 10-15 years. According to Pestel's project, Russia was to become a single centralized state with a republican form of government. Legislative power belonged to the People's Council consisting of 500 people, which was elected for a period of 5 years. The State Duma, elected at the assembly and consisting of 5 members, became the body of executive power. The highest control body was the Supreme Council of 120 citizens elected for life. The class division was eliminated, all citizens were endowed with political rights. Serfdom was destroyed. The land fund of each volost was divided into public (inalienable) and private half. From the first half, freed peasants and all citizens who wished to engage in farming received land. The second half consisted of state and private property and was subject to purchase and sale. The draft proclaimed the sacred right of personal property and established freedom of occupation and religion for all citizens of the republic.

Southern society recognized a necessary condition The success of the armed uprising in the capital, accordingly, the conditions for membership in the society were changed: now only a military man could become a member,” a decision was made on the strictest discipline and secrecy.

After the liquidation of the Welfare Union in St. Petersburg, a new secret society was immediately formed - Northern

,

the main core of which was N.M. Muravyov, NI. Turgenev, M. S. Lunin, S. P. Trubetskoy, E. P. Obolensky and I. I. Pushchin. Subsequently, the composition of the society expanded significantly. A number of its members moved away from the republican decisions of the Indigenous Council and returned to the idea of a constitutional monarchy. The program of the Northern Society can be judged by constitutional

project

Nikita

Muravyova

,

not accepted, however, as an official document of society. Russia became a constitutional monarchical state. A federal division of the country into 15 “powers” was introduced. Power was divided into legislative, executive and judicial. The highest legislative body was the bicameral People's Assembly, elected for a period of 6 years on the basis of a high property qualification. Legislative power in each “power” was exercised by a bicameral Sovereign Assembly, elected for 4 years. The emperor had executive power and became the “supreme official.” The highest judicial body of the federation was the Supreme Court. The class system was abolished, civil and political freedoms were proclaimed. Serfdom was abolished; in the latest version of the constitution, N. Muravyov provided for the allocation of freed peasants with land (2 dessiatines per yard). Landowner property was preserved.

However, everything great strength In Northern society, a more radical movement was gaining momentum, the head of which was K. F. Ryleev. His fame brought him literary activity: the satire on Arakcheev “To the Temporary Worker” (1820) and “Dumas”, which glorified the fight against tyranny, were especially popular. He joined the society in 1823 and a year later was elected its director. Ryleev adhered to republican views.

The most intense activity of the Decembrist organizations occurred in 1824-1825: preparations were made for an open armed uprising, and hard work was underway to harmonize the political platforms of the Northern and Southern societies. In 1824, it was decided to prepare and hold a unification congress by the beginning of 1826, and in the summer of 1826 to carry out a military coup. In the second half of 1825, the forces of the Decembrists increased: the Southern Society joined the Vasilkovsky council Society

connected

Slavs

.

It arose in 1818 as a secret political “Society of First Consent”, in 1823 it was transformed into the Society of United Slavs, the purpose of the organization was to create a powerful republican democratic federation of Slavic peoples.

In May 1821, the emperor became aware of the Decembrist conspiracy: to him reported on the plans and composition of the Welfare Union. But Alexander I limited himself to the words: “It’s not for me to execute them.”

Insurrection

14

December

1825

G

.

The sudden death of Alexander I in Taganrog, which followed 19

November

1825

g., changed the plans of the conspirators and forced them to act ahead of schedule.

Tsarevich Constantine was considered the heir to the throne. On November 27, the troops and population were sworn in to Emperor Constantine I. Only on December 12, 1825, an official message about his abdication came from Constantine, who was in Warsaw. A manifesto on the accession of Emperor Nicholas I immediately followed and on the 14th December In 1825, a “re-oath” was appointed. The interregnum caused discontent among the people and the army. The moment for the implementation of the plans of secret societies was extremely favorable. In addition, the Decembrists learned that the government had received denunciations about their activities, and on December 13, Pestel was arrested.

Plan coup d'etat was adopted during meetings of society members at Ryleev’s apartment in St. Petersburg. Decisive importance was attached to the success of the performance in the capital. At the same time, troops were supposed to move out in the south of the country, in the 2nd Army. One of the founders of the Union of Salvation, S. P

.

Trubetskoy

,

Colonel of the Guard, famous and popular among the soldiers. On the appointed day, it was decided to withdraw troops to Senate Square, prevent the oath of the Senate and State Council to Nikolai Pavlovich and, on their behalf, publish the “Manifesto to the Russian People,” which proclaimed the abolition of serfdom, freedom of the press, conscience, occupation and movement, the introduction of universal military service instead recruitment The government was declared deposed, and power was transferred to the Provisional Government until the representative Great Council made a decision on the form of government in Russia. The royal family was supposed to be arrested. The Winter Palace and the Peter and Paul Fortress were supposed to be captured with the help of troops, and Nicholas was to be killed.

But it was not possible to carry out the planned plan. A. Yakubovich, who was supposed to command the Guards naval crew and the Izmailovsky regiment during the capture of the Winter Palace and arrest the royal family, refused to complete this task for fear of becoming the culprit of regicide. The Moscow Life Guards Regiment appeared on Senate Square, and was later joined by sailors of the Guards crew and life grenadiers - a total of about 3 thousand soldiers and 30 officers. While Nicholas l was gathering troops to the square, Governor-General M. A. Miloradovich appealed to the rebels to disperse and was mortally wounded by P. G. Kakhovsky. It soon became clear that Nicholas had already sworn in the members of the Senate and the State Council. It was necessary to change the plan of the uprising, but S.P. Trubetskoy, who was called upon to lead the actions of the rebels, did not appear on the square. In the evening, the Decembrists elected a new dictator - Prince E. P. Obolensky, but time was lost. Nicholas I, after several unsuccessful cavalry attacks, gave the order to fire grapeshot from the cannons. 1,271 people were killed, and most of the victims - more than 900 - were among the sympathizers and curious people gathered in the square.

29

December

1825

G

.

WITH

.

AND

.

Muravyov-Apostol and M.P. Bestuzhev-Ryumin managed to raise the Chernigov regiment, stationed in the south, in the village of Trilesy. Government troops were sent against the rebels. 3 January

1826

G

.

The Chernigov regiment was destroyed.

In the 19th century A social movement, rich in content and methods of action, arose in Russia, which largely determined the future fate of the country.

In the first half of the 19th century. The Decembrist movement was of especially great historical significance. Their ideas became the banner of Russian liberalism. Inspired by the progressive ideas of the era, this movement aimed to overthrow the autocracy and eliminate serfdom. The Decembrists' speech in 1825 became an example of civic courage and dedication for young people. Thanks to this, the ideal of citizenship and the ideal of statehood were sharply opposed in the minds of an educated society. The blood of the Decembrists forever divided the intelligentsia and the state in Russia.

There were also serious weaknesses in this movement. The main one is the small number of their ranks. They saw their main support not in the people, but in the army, primarily in the guard. The Decembrists' speech widened the split between the nobility and the peasantry. The peasantry expected nothing but evil from the nobles. Throughout the 19th century. the peasants pinned their hopes for social justice only on the tsar. All speeches of the nobles, and then of the various democratic intelligentsia, were perceived incorrectly by them.

Already at the beginning of the century, Russian conservatism was formed as a political movement, the ideologist of which was the famous historian, writer and statesman N. M. Karamzin (1766 - 1826). He wrote that the monarchical form of government most fully corresponds to the existing level of development of morality and enlightenment of mankind. The sole power of the autocrat does not mean arbitrariness. The monarch was obliged to strictly observe the laws. The class structure of society is an eternal and natural phenomenon. The nobles were supposed to “rise” above other classes not only by their nobility of origin, but also by their moral perfection, education, and usefulness to society.

The works of N. M. Karamzin also contained individual elements theory of official nationality, developed in the 30s. XIX century Minister of Public Education S.S. Uvarov (1786 - 1855) and historian M.P. Pogodin (1800 - 1875). They preached the thesis about the inviolability of indigenous foundations Russian statehood, which included autocracy, Orthodoxy and nationality. This theory, which became the official ideology, was directed against the forces of progress and oppositional sentiments.

By the end of the 1830s. Among the advanced part of Russian society, several integral movements appear that offer their own concepts historical development Russia and its reconstruction programs.

Westerners (T. N. Granovsky, V. P. Botkin, E. F. Korsh, K. D. Kavelin) believed that Russia was following the European path as a result of the reforms of Peter 1. This should inevitably lead to the abolition of serfdom and the transformation of despotic state system into a constitutional one. The authorities and society must prepare and carry out well-thought-out, consistent reforms, with the help of which the gap between Russia and Western Europe will be eliminated.

The radically minded A. I. Herzen, N. P. Ogarev and V. G. Belinsky in the late 1830s and early 1840s, sharing the basic ideas of the Westerners, subjected the bourgeois system to the harshest criticism. They believed that Russia should not only catch up with Western European countries, but also take, together with them, a decisive revolutionary step towards a fundamentally new system - socialism.

The opponents of the Westerners were Slavophiles (A. S. Khomyakov, brothers I. V. and P. V. Kirievsky, brothers K. S. and I. S. Aksakov, Yu. M. Samarin, A. I. Koshelev). In their opinion, the historical path of Russia is radically different from the development of Western European countries. Western peoples, they noted, live in an atmosphere of individualism, private interests, hostility of classes, despotism on the blood of built states. At the heart of Russian history was a community, all members of which were connected by common interests. Orthodox Church further strengthened the original ability of the Russian person to sacrifice his own interests for the sake of common ones. The state power took care of the Russian people, supported necessary order, but did not interfere in spiritual, private, local life, listened sensitively to the opinion of the people, maintaining contact with them through Zemsky Sobors. Peter 1 destroyed this harmonious structure, introduced serfdom, which divided the Russian people into masters and slaves, the state under him acquired a despotic character. Slavophiles called for the restoration of the old Russian foundations of social state life: to revive the spiritual unity of the Russian people (for which serfdom should have been abolished); to overcome the despotic nature of the autocratic system, to establish the lost relationship between the state and the people. They hoped to achieve this goal by introducing widespread publicity; They also dreamed of the revival of Zemsky Sobors.

Westerners and Slavophiles, being different currents of Russian liberalism, had heated discussions among themselves and acted in the same direction. The abolition of serfdom and the democratization of the state structure - these are the primary tasks with the solution of which Russia should have begun to enter the new level development.

In the middle of the century, the most decisive critics of the authorities were writers and journalists. The ruler of the souls of democratic youth in the 40s. there was V. G. Belinsky (1811 - 1848), a literary critic who advocated the ideals of humanism, social justice and equality. In the 50s The magazine Sovremennik became the ideological center of young democrats, in which N. A. Nekrasov (1821 - 1877), N. G. Chernyshevsky (1828 - 1889), N. A. Dobrolyubov (1836 - 1861) began to play a leading role. Young people who stood for radical renewal of Russia gravitated towards the magazine. The ideological leaders of the magazine convinced readers of the necessity and inevitability of Russia's rapid transition to socialism, considering the peasant community the best form of people's life.

The reform intentions of the authorities initially met with understanding in Russian society. Magazines that took different positions - the Westernizing-liberal "Russian Messenger", the Slavophile "Russian Conversation" and even the radical "Sovremennik" - in 1856 - 1857. advocated the interaction of all social movements and joint support of the government’s aspirations. But as the nature of the impending peasant reform became clearer, the social movement lost its unity. If the liberals, criticizing the government on private issues, generally continued to support it, then the Sovremennik publicists - N.G. Chernyshevsky and N.A. Dobrolyubov - more sharply denounced both the government and the liberals.

A special position was occupied by A. I. Herzen (1812 - 1870), a brilliantly educated publicist, writer and philosopher, the true “Voltaire of the 19th century,” as he was called in Europe. In 1847, he emigrated from Russia to Europe, where he hoped to take part in the struggle for socialist transformations in the most advanced countries. But the events of 1848 dispelled his romantic hopes. He saw that the majority of the people did not support the proletarians heroically fighting on the barricades of Paris. In its foreign publications (almanac " polar Star" and the magazine "Bell", which I read a lot in the 50s. all thinking Russia) he exposed the reactionary aspirations of the highest dignitaries and criticized the government for indecisiveness. And yet, during these years, Herzen was closer precisely to the liberals than to Sovremennik. He continued to hope for a successful outcome of the reform and followed the activities of Alexander II with sympathy. The authors of Sovremennik believed that the authorities were incapable of just reform, and dreamed of an imminent popular revolution.

After the abolition of serfdom, the split in the social movement became deeper. The majority of liberals continued to count on the good will and reform capabilities of the autocracy, seeking only to push it in the right direction. At the same time, a significant part of educated society was captured by revolutionary ideas. This was largely due to serious changes in his social composition. It quickly lost its class-noble character, the boundaries between classes were destroyed. The children of peasants, townspeople, clergy, and impoverished nobility quickly lost social connections with the environment that gave birth to them, turning into commoner intellectuals, standing outside the classes, living their own, special lives. They sought to change Russian reality as quickly and radically as possible and became the main base of the revolutionary movement in the post-reform period.

The radically minded public, inspired by N.G. Chernyshevsky, sharply criticized the peasant reform, demanded more decisive and consistent changes, reinforcing these demands with the threat of a popular uprising. The authorities responded with repression. In 1861 – 1862 many figures of the revolutionary movement, including Chernyshevsky himself, were sentenced to hard labor. Throughout the 1860s. The radicals tried several times to create a strong organization. However, neither the group “Land and Freedom” (1862 - 1864), nor the circle of N. A. Ishutin (whose member D. V. Karakozov shot at Alexander II in 1866), nor “People’s Retribution” (1869) could become such. ) under the leadership of S. G. Nechaev.

At the turn of 1860 - 1870 The formation of the ideology of revolutionary populism is taking place. It received its complete expression in the works of M. Bakunin, P. Lavrov, N. Tkachev. These ideologists placed special hopes on the peasant community, viewing it as the embryo of socialism.

In the late 1860s - early 1870s. A number of populist circles arose in Russia. In the spring of 1874, their members began a mass outreach to the people, in which thousands of young men and women took part. It covered more than 50 provinces, from the Far North to Transcaucasia and from the Baltic states to Siberia. Almost all participants in the walk believed in the revolutionary receptivity of the peasants and in an imminent uprising: the Lavrists (propaganda trend) expected it in 2-3 years, and the Bakuninists (rebellious trend) - “in the spring” or “in the fall.” However, it was not possible to rouse the peasants to revolution. The revolutionaries were forced to reconsider their tactics and move on to more systematic propaganda in the countryside. In 1876, the organization “Land and Freedom” emerged, the main goal of which was declared to be the preparation of a people’s socialist revolution. The populists sought to create strongholds in the countryside for an organized uprising. However, “sedentary” activity also did not bring any serious results. In 1879, “Land and Freedom” split into “Black Redistribution” and “People’s Will”. The “Black Redistribution”, whose leader was G.V. Plekhanov (1856 - 1918), remained in its old positions. The activities of this organization turned out to be fruitless. In 1880, Plekhanov was forced to go abroad. "People's Will" brought political struggle to the forefront, striving to achieve the overthrow of the autocracy. The tactics of seizing power chosen by the Narodnaya Volya consisted of intimidation and disorganization of power through individual terror. An uprising was gradually being prepared. No longer relying on the peasants, the Narodnaya Volya tried to organize students, workers, and penetrate the army. In the fall of 1879, they launched a real hunt for the Tsar, which ended with the murder of Alexander II on March 1, 1881.

In the 60s The process of formalizing Russian liberalism as an independent social movement begins. Famous lawyers B. N. Chicherin (1828 - 1907), K. D. Kavelin (1817 - 1885) reproached the government for hasty reforms, wrote about the psychological unpreparedness of some segments of the population for change, advocated a calm, without shocks, "growing" of society into new forms of life. They fought both conservatives and radicals who called for popular revenge on the oppressors. At this time, their socio-political base became zemstvo bodies, new newspapers and magazines, and university professors. In the 70-80s. Liberals are increasingly coming to the conclusion that deep political reforms are necessary.

IN late XIX V. The liberal movement was slowly on the rise. During these years, ties between zemstvos were established and strengthened, meetings of zemstvo leaders took place, and plans were developed. Liberals considered the introduction of a constitution, representative institutions, glasnost and civil rights. On this platform, in 1904, the organization “Union of Liberation” emerged, uniting liberal Zemstvo citizens and the intelligentsia. While advocating a constitution, the “Union” put forward in its program some moderate socio-economic demands, primarily on the peasant issue: the alienation of part of the landowners’ lands for ransom, the liquidation of plots, etc. Characteristic feature The liberal movement continued to reject revolutionary methods of struggle. The socio-political base of liberals is expanding. The zemstvo and city intelligentsia, scientific and educational societies are increasingly joining their movement. In terms of numbers and activity, the liberal camp is now not inferior to the conservative one, although it is not equal to the radical democratic one.

Populism is experiencing a crisis phenomenon in these years. The liberal wing in it is significantly strengthened, whose representatives (N.K. Mikhailovsky, S.N. Krivenko, V.P. Vorontsov, etc.) hoped to bring populist ideals to life peacefully. Among liberal populism, the “theory of small deeds” arose. She focused the intelligentsia on daily, everyday work to improve the situation of the peasants.

The liberal populists differed from the liberals primarily in that socio-economic transformations were of paramount importance to them. They considered the struggle for political freedoms a secondary matter. The revolutionary wing of populism, weakened by government repression, managed to intensify its activities only at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. In 1901, the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRs) emerged, who tried to embody the ideals of revolutionary populism in their program. They retained the thesis about the peasant community as the embryo of socialism. The interests of the peasantry, the Social Revolutionaries argued, are identical to the interests of the workers and the working intelligentsia. All these are the “working people”, of which they considered their party to be the vanguard. In the coming socialist revolution the main role allocated to the peasantry. On the agrarian question, they advocated the “socialization of the land,” that is, the abolition of private ownership of it and the equal distribution of land among everyone who wants to cultivate it. The Social Revolutionaries advocated the overthrow of the autocracy and the convening Constituent Assembly, which will determine the nature of the Russian political system. They considered individual terror to be the most important means of revolutionary struggle, along with widespread agitation among peasants and workers.

In 1870 - 1880 Russian is also gaining strength labor movement. And in St. Petersburg and Odessa the first organizations of the proletariat arose - the Northern Union of Russian Workers and the South Russian Union of Workers. They were relatively few in number and were influenced by populist ideas. Already in the 80s. The labor movement has expanded significantly, and elements of what it did at the beginning of the twentieth century appear in it. the labor movement is one of the most important political factors in the life of the country. The largest strike in the post-reform years, the Morozov strike (1885), confirmed this situation.

The authorities’ ignorance of the needs of the working class has led to the fact that supporters of Marxism flock to the working environment and find support there. They see the proletariat as the main revolutionary force. In 1883, the “Emancipation of Labor” group, led by Plekhanov, emerged in exile in Geneva. Having switched to Marxist positions, he abandoned many provisions of the populist teaching. He believed that Russia had already irrevocably embarked on the path of capitalism. The peasant community is increasingly split into rich and poor, and therefore cannot be the basis for building socialism. Criticizing the populists, Plekhanov argued that the struggle for socialism also included the struggle for political freedoms and a constitution. The leading force in this struggle will be the industrial proletariat. Plekhanov noted that there must be a more or less long interval between the overthrow of the autocracy and the socialist revolution. Forcing the socialist revolution could lead, in his opinion, to the establishment of “renewed tsarist despotism on a communist lining.”

The group saw its main task as promoting Marxism in Russia and rallying forces to create a workers’ party. With the advent of this group, Marxism in Russia emerged as an ideological movement. It supplanted populism and, in the bitter struggle against it, inherited many of its features.

In the 80s In Russia, Marxist circles of Blagoev, Tochissky, Brusnev, Fedoseev appeared, disseminating Marxist views among the intelligentsia and workers. In 1895, the “Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class”, headed by V.I. Lenin, emerged in St. Petersburg. Following his example, similar organizations are being created in other cities. In 1898, on their initiative, the First Congress of the RSDLP was held in Minsk, announcing the creation of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. But in fact the party was created only in 1903 at the Second Congress. After heated debates, the RSDLP program was adopted there. It consisted of two parts. The minimum program determined the immediate tasks of the party: the overthrow of the autocracy and the establishment of a democratic republic, an 8-hour working day, the return of plots of land to the peasants and the abolition of redemption payments, etc. This part of the program was in no way more revolutionary than the Socialist Revolutionary Party, and on the agrarian issue it was closer to the liberal one. The maximum program aimed to implement the socialist revolution and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat. These demands put the RSDLP in a special position, turning it into an extreme, extremist organization. Such a goal excluded concessions and compromises, cooperation with representatives of other socio-political forces. The adoption of the maximum program at the congress and the results of the elections to the central bodies of the party marked the victory of the radical wing of the RSDLP - the Bolsheviks, led by V. I. Lenin. Their opponents, who after this congress received the name Mensheviks, insisted that the party proceed in its activities only from a minimum program. Bolsheviks and Mensheviks turned into two independent flow in the RSDLP. They sometimes moved away, sometimes closer, but never completely merged. In fact, these were two parties that differed significantly in ideological and organizational issues. The Mensheviks were guided primarily by the experience of Western European socialist parties. The Bolshevik Party was built on the model of “People's Will” and was aimed at seizing power.

As for the conservative camp, in the post-reform period it is experiencing ideological confusion caused by a huge complex of complex economic and social problems that Russia faced during these years.

The talented journalist M.N. Katkov called in his articles for the establishment of a regime in the country “ strong hand" K. P. Pobedonostsev resolutely warned Russians against introducing a constitutional system. He considered the idea of representation to be essentially false, since it is not the people, but only their representatives (and not the most honest, but only dexterous and ambitious) who participate in political life. Correctly noting the shortcomings of the representative system and parliamentarism, he did not want to recognize their enormous advantages. Conservatives, being critical of Russian reality, including the activities of jury courts, zemstvos, and the press (which were not at all ideal), demanded that the tsar appoint honest officials to leadership positions, demanded that the peasants be given only an elementary education, strictly religious in content, They demanded merciless punishment for dissent. They avoided discussing such issues as the lack of land of peasants, the arbitrariness of entrepreneurs, low level the lives of a huge part of the people. Their ideas essentially reflected the powerlessness of conservatives in the face of the formidable problems that faced society at the end of the 19th century. Moreover, by the end of the century, among them there were already many ideologists who sharply criticized government policies for ineffectiveness and even reactionaryness.

Questions for self-control

1. What were the features of the socio-economic and political development of Russia in the first half of the 19th century?

2. What were the reasons for the reforms of the 60s - early 70s. XIX century?

3. What changes occurred in the position of the nobility and peasantry as a result of the abolition of serfdom?

4. What are the consequences and significance of bourgeois reforms for Russia?

5. What impact did counter-reforms have on the development of the country? Alexandra III?

6. Russian and Western liberalism: general and specific.

7. Historical fate of populism in Russia.

Literature

Great reforms in Russia. 1856 – 1874 – M., 1992.

Mironenko S.V. Autocracy and reforms. Political struggle in Russia at the beginning of the 19th century. – M., 1989.

Mironov B. N. Social history of Russia during the imperial period (XVIII - early XX centuries). T. 1 – 2. – St. Petersburg, 2000.

Domestic history: Reader. – Kirov, 2003.

Pirumova N. M. Zemskaya intelligentsia and its role in the social struggle before the beginning of the twentieth century. – M., 1986.

Russian autocrats. – M., 1992.

Semennikova L. I. Russia in the world community of civilizations. – Bryansk, 2002.

Solovyova A.M. Industrial revolution in Russia XIX V. – M., 1990.

Tarle E.V. Napoleon's invasion of Russia. – M., 1992.

Tomsinov V.A. The luminary of the Russian bureaucracy. Historical portrait MM. Speransky. – M., 1991.

Troitsky I.M. III department under Nicholas I. - L., 1990.

Troitsky N.A. Russia in the 19th century. Lecture course. – M., 1999.

Fedorov V.A. Decembrists and their time. – M., 1997.

The 19th century entered the history of Russia as a period of socio-economic changes. The feudal system was replaced by the capitalist system, and the agrarian economic system was replaced by an industrial one. Fundamental changes in the economy entailed changes in society - new layers of society appeared, such as the bourgeoisie, intelligentsia, and proletariat. These layers of society increasingly asserted their rights to the social and economic life of the country, and a search was underway for ways to organize themselves. The traditional hegemon of social and economic life- the nobility could not help but realize the need for changes in the economy, and as a consequence - in the social and socio-political life of the country.

At the beginning of the century, it was the nobility, as the most enlightened layer of society, that played the leading role in the process of realizing the need for changes in the socio-economic structure of Russia. It was representatives of the nobility who created the first organizations that set themselves not just replacing one monarch with another, but changing the political and economic system of the country. The activities of these organizations went down in history as the Decembrist movement.

Decembrists.

"Union of Salvation" is the first secret organization created by young officers in February 1816 in St. Petersburg. It consisted of no more than 30 people, and was not so much an organization as a club that united people who wanted to destroy serfdom and fight the autocracy. This club had no clear goals, much less methods for achieving them. Having existed until the autumn of 1817, the Union of Salvation was dissolved. But at the beginning of 1818, its members created the “Union of Welfare”. It has already included about 200 military and civilian officials. The goals of this “Union” did not differ from the goals of its predecessor - the liberation of the peasants and the implementation of political reforms. There was an understanding of the methods for achieving them - propaganda of these ideas among the nobility and support for the liberal intentions of the government.

But in 1821, the tactics of the organization changed - citing the fact that the autocracy was not capable of reforms; at the Moscow congress of the “Union” it was decided to overthrow the autocracy by armed means. Not only the tactics changed, but also the structure of the organization itself - instead of a club of interests, clandestine, clearly structured organizations were created - the Southern (in Kyiv) and Northern (in St. Petersburg) societies. But, despite the unity of goals - the overthrow of the autocracy and the abolition of serfdom - there was no unity between these organizations in the future political structure countries. These contradictions were reflected in the program documents of the two societies - “Russian Truth” proposed by P.I. Pestel (Southern Society) and “Constitutions” by Nikita Muravyov (Northern Society).

P. Pestel saw the future of Russia as a bourgeois republic, led by a president and a bicameral parliament. Northern society, led by N. Muravyov, proposed a constitutional monarchy as a state structure. With this option, the emperor, as a government official, exercised executive power, while legislative power was vested in a bicameral parliament.

On the issue of serfdom, both leaders agreed that the peasants needed to be freed. But whether to give them land or not was a matter of debate. Pestel believed that it was necessary to allocate by taking away the land and too large landowners. Muravyov believed that there was no need - vegetable gardens and two acres per yard would be enough.

The apotheosis of the activities of secret societies was the uprising of December 14, 1825 in St. Petersburg. In essence, it was an attempt at a coup d'etat, the latest in a series of coups that replaced emperors on the Russian throne throughout the 18th century. December 14, the day of the coronation of Nicholas I, younger brother Alexander I, who died on November 19, the conspirators brought troops to the square in front of the Senate, a total of about 2,500 soldiers and 30 officers. But, for a number of reasons, they were unable to act decisively. The rebels remained standing in a “square” on Senate Square. After fruitless negotiations between the rebels and representatives of Nicholas I that lasted all day, the “square” was shot with grapeshot. Many rebels were injured or killed, all the organizers were arrested.

579 people were involved in the investigation. But only 287 were found guilty. On July 13, 1826, five leaders of the uprising were executed, another 120 were sentenced to hard labor or settlement. The rest escaped with fear.

This attempt at a coup d'état went down in history as the “Decembrist uprising.”

The significance of the Decembrist movement is that it gave impetus to the development of socio-political thought in Russia. Being not just conspirators, but having political program, the Decembrists gave the first experience of political “non-systemic” struggle. The ideas set out in the programs of Pestel and Muravyov found a response and development among subsequent generations of supporters of the reorganization of Russia.

Official nationality.

The Decembrist uprising had another significance - it gave rise to a response from the authorities. Nicholas I was seriously frightened by the coup attempt and during his thirty-year reign he did everything to prevent it from happening again. authorities established strict control over public organizations and the mood in various circles of society. But punitive measures were not the only thing the authorities could take to prevent new conspiracies. She tried to offer her own social ideology designed to unite society. It was formulated by S.S. Uvarov in November 1833 when he took office as Minister of Public Education. In his report to Nicholas I, he quite succinctly presented the essence of this ideology: “Autocracy. Orthodoxy. Nationality."

The author interpreted the essence of this formulation as follows: Autocracy is a historically established and established form of government that has grown into the way of life of the Russian people; Orthodox faith– guardian of morality, the basis of the traditions of the Russian people; Nationality is the unity of the king and the people, acting as a guarantor against social upheaval.

This conservative ideology was adopted as a state ideology and the authorities successfully adhered to it throughout the reign of Nicholas I. And until the beginning of the next century, this theory continued to successfully exist in Russian society. The ideology of the official nationality laid the foundation for Russian conservatism as part of socio-political thought. West and East.

No matter how hard the authorities tried to develop a national idea, setting a rigid ideological framework of “Autocracy, Orthodoxy and Nationality,” it was during the reign of Nicholas I that Russian liberalism was born and formed as an ideology. Its first representatives were interest clubs among the nascent Russian intelligentsia, called “Westerners” and “Slavophiles.” They weren't political organizations, and the ideological movements of like-minded people, who created an ideological platform in disputes, later on which full-fledged political organizations and parties would emerge.

Writers and publicists I. Kireevsky, A. Khomyakov, Yu. Samarin, K. Aksakov and others considered themselves Slavophiles. Most prominent representatives the camps of the Westerners were P. Annenkov, V. Botkin, A. Goncharov, I. Turgenev, P. Chaadaev. A. Herzen and V. Belinsky were in solidarity with the Westerners.

Both of these ideological movements were united by criticism of the existing political system and serfdom. But, being unanimous in recognizing the need for change, Westerners and Slavophiles assessed the history and future structure of Russia differently.

Slavophiles:

- Europe has exhausted its potential, and it has no future.

- Russia is a separate world, due to its special history, religiosity, and mentality.

- Orthodoxy is the greatest value of the Russian people, opposing rationalistic Catholicism.

- The village community is the basis of morality, not spoiled by civilization. The community is the support of traditional values, justice and conscience.

- Special relationship between the Russian people and the authorities. The people and the government lived according to an unwritten agreement: there are us and them, the community and the government, each with their own life.

- Criticism of the reforms of Peter I - the reform of Russia under him led to a disruption of the natural course of its history, disrupted the social balance (agreement).

Westerners:

- Europe is the world civilization.

- There is no originality of the Russian people, there is their backwardness from civilization. Russia for a long time was “outside history” and “outside civilization.”

- had a positive attitude towards the personality and reforms of Peter I; they considered his main merit to be Russia’s entry into the fold of world civilization.

- Russia is following in the footsteps of Europe, so it must not repeat its mistakes and adopt positive experience.

- The engine of progress in Russia was considered not the peasant community, but the “educated minority” (intelligentsia).

- The priority of individual freedom over the interests of government and the community.

What is common between Slavophiles and Westerners:

- Abolition of serfdom. Liberation of peasants with land.

- Political freedoms.

- Rejection of the revolution. Only the path of reforms and transformations.

Discussions between Westerners and Slavophiles were of great importance for the formation of socio-political thought and liberal-bourgeois ideology.

A. Herzen. N. Chernyshevsky. Populism.

Even greater critics of the official ideology of conservatism than liberal Slavophiles and Westerners were representatives of the revolutionary democratic ideological trend. The most prominent representatives of this camp were A. Herzen, N. Ogarev, V. Belinsky and N. Chernyshevsky. The theory of communal socialism they proposed in 1840–1850 was that:

- Russia is going its own way historical path, different from Europe.

- capitalism is not a characteristic, and therefore not acceptable, phenomenon for Russia.

- autocracy does not fit into the social structure of Russian society.

- Russia will inevitably come to socialism, bypassing the stage of capitalism.

- the peasant community is the prototype of a socialist society, which means that Russia is ready for socialism.

The method of social transformation is revolution.

The ideas of “community socialism” found a response among the various intelligentsia, who from the middle of the 19th century began to play an increasingly prominent role in the social movement. It is with the ideas of A. Herzen and N. Chernyshevsky that the movement that came to the forefront of Russian socio-political life in 1860–1870 is associated. It will be known as Populism.

The goal of this movement was a radical reorganization of Russia on the basis of socialist principles. But there was no unity among the populists on how to achieve this goal. Three main directions were identified:

Propagandists. P. Lavrov and N. Mikhailovsky. In their opinion, the social revolution should be prepared by the propaganda of the intelligentsia among the people. They rejected the violent path of restructuring society.

Anarchists. Chief ideologist M. Bakunin. Denial of the state and its replacement by autonomous societies. Achieving goals through revolution and uprisings. Continuous small riots and uprisings are preparing a big revolutionary explosion.

Conspirators. Leader - P. Tkachev. Representatives of this part of the populists believed that it is not education and propaganda that prepares the revolution, but the revolution will give enlightenment to the people. Therefore, without wasting time on enlightenment, it is necessary to create a secret organization of professional revolutionaries and seize power. P. Tkachev believed that a strong state is necessary - only it can turn the country into a large commune.

The heyday of populist organizations occurred in the 1870s. The most massive of them was “Land and Freedom”, created in 1876, it united up to 10 thousand people. In 1879, this organization split; the stumbling block was the question of methods of fighting. A group led by G. Plekhpnov, V. Zasulich and L. Deych, who opposed terror as a way of fighting, created the organization “Black Redistribution”. Their opponents, Zhelyabov, Mikhailov, Perovskaya, Figner, advocated terror and the physical elimination of government officials, primarily the tsar. Supporters of terror organized the People's Will. It was the members of Narodnaya Volya who, since 1879, made five attempts on the life of Alexander II, but only on March 1, 1881 they managed to achieve their goal. This was the end both for Narodnaya Volya itself and for other populist organizations. The leadership of "Narodnaya Volya" in in full force was arrested and executed by court order. More than 10 thousand people were brought to trial for the murder of the emperor. Populism never recovered from such a defeat. In addition, peasant socialism as an ideology had exhausted itself by the beginning of the 20th century - the peasant community ceased to exist. It was replaced by commodity-money relations. Capitalism developed rapidly in Russia, penetrating ever deeper into all spheres of social life. And just as capitalism replaced the peasant community, so social democracy replaced populism.

Social Democrats. Marxists.

With the defeat of the populist organizations and the collapse of their ideology, the revolutionary field of socio-political thought was not left empty. In the 1880s, Russia became acquainted with the teachings of K. Marx and the ideas of the Social Democrats. The first Russian social democratic organization was the Liberation of Labor group. It was created in 1883 in Geneva by members of the Black Redistribution organization who emigrated there. The Liberation of Labor group is credited with translating the works of K. Marx and F. Engels into Russian, which allowed their teaching to quickly spread in Russia. The basis of the ideology of Marxism was outlined back in 1848 in the “Manifesto of the Communist Party” and by the end of the century had not changed: a new class came to the forefront of the struggle for the reconstruction of society - hired workers industrial enterprises– proletariat. It is the proletariat that will carry out the socialist revolution as an inevitable condition for the transition to socialism. Unlike the populists, Marxists understood socialism not as a prototype of a peasant community, but as a natural stage in the development of society following capitalism. Socialism is equal rights to the means of production, democracy and social justice.

Since the beginning of the 1890s, Social Democratic circles have emerged one after another in Russia; Marxism was their ideology. One of such organizations was the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class, created in St. Petersburg in 1895. Its founders were the future leaders of the RSDLP - V. Lenin and Yu. Martov. The purpose of this organization was to promote Marxism and promote the workers' strike movement. At the beginning of 1897, the organization was liquidated by the authorities. But already in the next year, 1898, at the congress of representatives of social democratic organizations in Minsk, the foundation of the future party was laid, which finally took shape in 1903 at the congress in London in the RSDLP.

The 19th century in Russia is remarkable in that in a hundred years public thought has gone from a complete understanding of the divinity and infallibility of royal power to an equally complete understanding of the need for fundamental changes in the state structure. From the first small groups of conspirators who were not entirely clear about their goals and ways to achieve them (Decembrists), to the creation of massive, well-organized parties with specific tasks and plans for achieving them (RSDLP). How did this happen?

Prerequisites

By the beginning of the 19th century, the main irritant of public thought was serfdom. Progressive thinking people of that time, starting with the landowners themselves and ending with the members royal family, it became clear that serfdom urgently needed to be abolished. Of course, the majority of landowners did not want to change the existing state of affairs. A new socio-political movement has emerged in Russia - the movement for the abolition of serfdom.

Thus, the basis for the organizational design of conservatism and liberalism began to appear. Liberals advocated changes that were to be initiated by the government. Conservatives sought to maintain the status quo. Against the backdrop of the struggle between these two directions, a certain part of society began to have thoughts about the revolutionary reorganization of Russia.

Social and political movements in Russia began to manifest themselves more actively after the Russian army marched into Europe. Comparison of European realities with life at home was clearly not in favor of Russia. The first to act were revolutionary-minded officers who returned from Paris.

Decembrists

Already in 1816 in St. Petersburg, these officers formed the first socio-political movement. It was the “Union of Salvation” of 30 people. They clearly saw the goal (the elimination of serfdom and the introduction of a constitutional monarchy) and had no idea how this could be achieved. The consequence of this was the collapse of the “Union of Salvation” and the creation in 1818 of a new “Union of Welfare”, which already included 200 people.

But due to different views on the future fate of the autocracy, this union lasted only three years and dissolved itself in January 1821. Its former members organized two societies in 1821-1822: “Southern” in Little Russia and “Northern” in St. Petersburg. It was their joint performance on Senate Square on December 14, 1825 that later became known as the Decembrist uprising.

Finding ways

The next 10 years in Russia were marked by the harsh reactionism of the regime of Nicholas I, which sought to suppress all dissent. There was no talk of creating any serious movements or unions. Everything remained at the circle level. Groups of like-minded people gathered around the publishers of magazines, the capital’s salons, at universities, among officers and officials, discussing a common sore point for everyone: “What to do?” But the circles were also persecuted quite harshly, which led to the extinction of their activities already in 1835.

Nevertheless, during this period, three main socio-political movements were quite clearly defined in their relation to the existing regime in Russia. These are conservatives, liberals and revolutionaries. The liberals, in turn, were divided into Slavophiles and Westerners. The latter believed that Russia needed to catch up with Europe in its development. Slavophiles, on the contrary, idealized pre-Petrine Rus' and called for a return to the state structure of those times.

Abolition of serfdom

By the 1940s, hopes for reform from the authorities began to fade. This caused the activation of revolutionary-minded sections of society. The ideas of socialism began to penetrate into Russia from Europe. But the followers of these ideas were arrested, tried and sent into exile and hard labor. By the mid-50s, there was no one to take any active action, or simply talk about the reorganization of Russia. The most active public figures lived in exile or served hard labor. Those who managed to emigrate to Europe.

But socio-political movements in Russia in the first half of the 19th century still played their role. Alexander II, who ascended the throne in 1856, spoke from the first days about the need to abolish serfdom, took concrete steps to formalize it legally, and in 1861 signed the historical Manifesto.

Activation of revolutionaries

However, the half-heartedness of the reforms, which did not meet the expectations of not only the peasants, but also the Russian public in general, caused a new surge of revolutionary sentiments. Proclamations from various authors began to circulate in the country, of a very diverse nature: from moderate appeals to the authorities and society about the need for deeper reforms, to calls for the overthrow of the monarchy and revolutionary dictatorship.

The second half of the 19th century in Russia was marked by the formation of revolutionary organizations that not only had goals, but also developed plans for their implementation, although not always realistic. The first such organization was the “Land and Freedom” union in 1861. The organization planned to implement its reforms with the help of a peasant uprising. But when it became clear that there would be no revolution, Land and Freedom dissolved itself at the beginning of 1864.

In the 70-80s, the so-called populism developed. Representatives of Russia's nascent intelligentsia believed that in order to accelerate change, it was necessary to appeal directly to the people. But there was no unity among them either. Some believed that it was necessary to limit ourselves to educating the people and explaining the need for change and only then talk about revolution. Others called for the abolition of the centralized state and the anarchic federalization of peasant communities as the basis of the country's social order. Still others planned the seizure of power by a well-organized party through a conspiracy. But the peasants did not follow them, and the riot did not happen.

Then, in 1876, the populists created the first truly large, well-covered revolutionary organization called “Land and Freedom”. But here, too, internal disagreements led to a split. Supporters of terrorism organized the “People's Will”, and those who hoped to achieve changes through propaganda gathered in the “Black Redistribution”. But these socio-political movements achieved nothing.

In 1881, the Narodnaya Volya killed Alexander II. However, the revolutionary explosion they expected did not happen. Neither the peasants nor the workers rebelled. Moreover, most of the conspirators were arrested and executed. And after the assassination attempt on Alexander III in 1887, Narodnaya Volya was completely defeated.

Most active

During these years, the penetration of Marxist ideas into Russia began. In 1883, the organization “Emancipation of Labor” was formed in Switzerland under the leadership of G. Plekhanov, who substantiated the inability of the peasantry to change through revolution and placed hope in the working class. Basically, the socio-political movements of the 19th century by the end of the century in Russia were strongly influenced by the ideas of Marx. Propaganda was carried out among the workers, they were called upon to strike and go on strike. In 1895, V. Lenin and Y. Martov organized the “Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class,” which became the basis for the further development of various social democratic trends in Russia.

The liberal opposition, meanwhile, continued to advocate for the peaceful implementation of reforms “from above,” trying to prevent a revolutionary solution to the problems facing Russian society. Thus, the active role of socio-political movements of a Marxist orientation had a decisive influence on the fate of Russia in the 20th century.

Wandering from one extreme to another is not unusual for Russia. Therefore, one should not be surprised at the growth of radicalism in the liberal 19th century, rich in revolutionary upheavals. Russian emperors The Alexanders, both the first and the second, inactively indulged the moderate liberals, and society, on the contrary, was ripe for radical changes in all spheres of the country's life. The emerging social demand for radicalism led to the emergence of ardent adherents of extremely decisive positions and actions.

The beginning of radicalism with a revolutionary overtones was laid by the secret societies of the Decembrists, which appeared in 1816. The creation within the framework of the organization of the Northern and Southern societies, which developed program documents (radical republican “Russian Truth” by Pestel and moderate-monarchical “Constitution” by Muravyov) of revolutionary transformations, led to the preparation of a coup d’etat.

The action on December 14, 1825 to seize power, introduce a constitutional system and announce the convening of the Russian Great Council, with an agenda of future fate the country failed for a number of objective and subjective reasons. However, the tragic events developed in the growth of Russian radicalism in subsequent periods national history XIX century.

Communal socialism of Alexander Herzen

V.I. Lenin noted that “the Decembrists woke up Herzen” with the ideas of the radical P. Pestel.

A. I. Herzen called his idol “a socialist before socialism” and, under the influence of his views, created the theory of “Russian communal socialism.” According to Alexander Ivanovich, this radical theory could provide a transition to socialism, bypassing capitalism.

The peasant community was to play a decisive role in such a revolutionary leap. Herzen believed that the Western path of development had no prospects due to the lack of a real spirit of socialism. The spirit of money and profit, pushing the West onto the path of bourgeois development, will ultimately destroy it.

Utopian socialism of Petrashevsky

The well-educated official and talented organizer M. V. Butashevich-Petrashevsky contributed to the penetration of the ideas of utopian socialism into Russian soil. In the circle he created, like-minded people heatedly discussed radical revolutionary and reform ideas and even organized the work of a printing house.

Despite the fact that their activities were limited only to conversations and rare proclamations, the gendarmes discovered the organization, and the court, under the supervision of Nicholas I himself, sentenced the Petrashevites to cruel punishment. The rational grain of the utopian ideas of Petrashevsky and his followers was a critical attitude towards capitalist civilization.

Revolutionary Populist Movement

With the beginning of the “Great Reforms”, Russian public consciousness underwent a significant split: one part of the progressive public plunged into liberalism, the other part preached revolutionary ideas. In the worldview of the Russian intelligentsia, the phenomenon of nihilism began to occupy an important place, as a certain form of moral assessment of new social phenomena. These ideas are clearly reflected in the novel “What to Do” by Nikolai Chernyshevsky.

Chernyshevsky’s views influenced the emergence of student circles, among which the “Ishutinites” and “Chaikovites” shone brightly. The ideological basis of the new associations was “Russian peasant socialism”, which passed into the phase of “populism”. Russian populism of the 19th century went through three stages:

- Proto-populism in the 50-60s.

- The heyday of populism in the 60-80s.

- Neo-populism from the 90s to the beginning of the 20th century.

The ideological successors of the populists were the socialist revolutionaries, known in popular historiography as the “Socialist Revolutionaries.”

The basis of the doctrinal principles of the populists were the provisions that:

- capitalism is a force that turns traditional values into ruins;

- the development of progress can be based on the socialist link - the community;

- The duty of the intelligentsia to the people is to induce them to revolution.

The Populist movement was heterogeneous; there are two main directions in it:

- Propaganda (moderate or liberal).

- Revolutionary (radical).

According to the level of increase in radicalism in populism, the following hierarchy of trends is built:

- Firstly, conservative (A. Grigoriev);

- Secondly, reformist (N. Mikhailovsky);

- Thirdly, revolutionary liberal (G. Plekhanov);

- Fourthly, social revolutionary (P. Tkachev, S. Nechaev);

- Fifthly, anarchist (M. Bakunin, P. Kropotkin).

Radicalization of populism

The idea of paying the debt to the people called upon the intelligentsia to a missionary movement known as “going to the people.” Hundreds of young people went to the villages as agronomists, doctors and teachers. The efforts were in vain, the tactics did not work.

The failure of the mission of “going to the people” was reflected in the creation of the revolutionary organization “Land and Freedom” in 1876.

Three years later, it split into the liberal “Black Redistribution” and the radical “People’s Will” (A. Zhelyabov, S. Perovskaya), which chose the tactics of individual terror as the main tool for promoting the social revolution. The apotheosis of their activity was the assassination of Alexander II, which entailed a reaction that emasculated populism as a mass movement.

Marxism is the crown of radicalism

Many populists, after the defeat of the organization, became Marxists. The goal of the movement was to overthrow the power of the exploiters, establish the primacy of the proletariat and create a communist society without private property. G. Plekhanov is considered the first Marxist in Russia, who is impossible to with good reason considered a radical.

True radicalism was brought to Russian Marxism by V. I. Ulyanov (Lenin).

In his work “The Development of Capitalism in Russia,” he argued that capitalism in Russia in the last decade of the 19th century had become a reality, and therefore the local proletariat was ready for the revolutionary struggle and was able to lead the peasantry. This position became the basis for the organization of a radical proletarian party in 1898, which turned the world upside down twenty years later.

Radicalism as the main method of social transformation in Russia

The historical development of the Russian state created the conditions for the emergence and development of radicalism in the process of social transformation. This was greatly facilitated by:

- extremely low standard of living for the majority of the country's population;

- the huge income gap between rich and poor;

- excess privileges for some, lack of rights for other groups of the population;

- lack of political and civil rights;

- arbitrariness and corruption of officials and more.

Overcoming these problems requires decisive action. If the authorities do not dare to take drastic steps, then radicalism as a political movement will again take a leading position in the political life of the country.