Who is the Iron Chancellor? Iron Chancellor. "Bismarck" in service: the role of super-dreadnoughts in the Kriegsmarine battle plans

The fate of the Bismarck is very indicative. The battle in the Denmark Strait once again showed the futility of developing ships without air cover. Archaic biplanes "CWarfish turned out to be a formidable opponent even for the newest and perfectly protected battleship, and the Bismarck remained lying on the seabed, still serving as a reminder: there are no unsinkable ships!

April 1, 2015 will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of the Prussian military-political leader Otto von Bismarck, the man who changed the face of Germany. In this regard, one cannot help but recall its equally famous “namesake” - the battleship Bismarck, which received its name according to the good tradition of naming ships in honor of great historical personalities.

"Versailles Fleet" of Germany

After the First World War, Germany was publicly humiliated at the Versailles Conference, becoming a “switchman” on a planetary scale. In particular, it was forbidden to have a high seas fleet, the basis of which in those years were battleships. All the main combat units of the German fleet either rested on the seabed or went to the Entente countries. Among the latter were ten dreadnoughts and five battlecruisers. But the years passed, and Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Workers' Party rose to the political Olympus of the Weimar Republic. For Hitler, the possession of full-fledged battleships was not only a military issue, but also a political one. Germany sought to restore its military presence at sea, which, according to naval theorists of the time, could only be ensured by dreadnoughts.

Birth of a Giant

On March 18, 1935, Germany unilaterally denounced the Treaty of Versailles. There was no harsh reaction from the leading European states - moreover, on June 18 of the same year, the Anglo-German naval agreement was published, according to which the Third Reich received the right to build ships of the 1st rank in the ratio of 100 to 35 (where 100 is the share England, and 35 - Germany).

At that time, Germany had three battlecruisers of the Deutschland type, and in 1935-36 “pocket battleships” with unlucky names for the German fleet - Scharnhorst and Gneisenau - were launched. These ships, being much more powerful and large-tonnage compared to the Deutschland class, were still noticeably inferior to their British classmates. The German sailors needed a breakthrough - something that would immediately bring Germany on the same level as the rulers of the oceans - the USA and Great Britain. A year after the fateful year of 1935, work began on the building stocks of the Blom und Voss company on the construction of the most powerful Bismarck-class battleship in the world at that time.

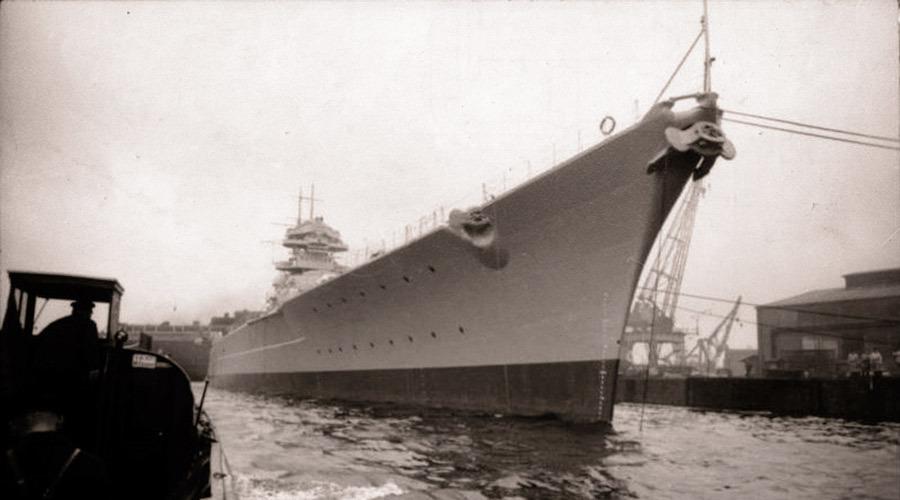

Battleship Bismarck in the Kiel Strait, 1940

Source - waralbum.ru

Being a direct development of the Scharnhorst, the new super-dreadnought had a third greater displacement (50,900 tons) and a length of over 253 m. The traditionally cautious Germans equipped the ship with extremely advanced armor - the main armor belt extended over 70% of the hull length, and its thickness ranged from 170 to 320 mm. The additional armor (upper belt, traverses and deck) was also impressive: the thickness of the frontal armor of the main caliber turrets was 360 mm, and the deckhouse - from 220 to 350 mm.

|

Displacement |

41,700 t – standard; 50,900 t – full |

|

Length |

251 m – the largest; 241.5 m – between perpendiculars |

|

Width |

|

|

Draft |

|

|

Booking |

belt – 320–170 mm; upper belt – 145 mm; traverses – 220–145 mm; longitudinal bulkhead – 30–25 mm; main gun towers – 360–130 mm; GK barbettes – 340–220 mm; SK towers – 100–40 mm; barbettes SK – 80–20 mm; deck – 50–80 + 80–95 mm (slopes – 110–120 mm); cutting 350–220 mm; anti-torpedo bulkhead – 45 mm |

|

Engines |

3 turbo gear units; 12 Wagner steam boilers |

|

Power |

|

|

Mover |

|

|

Travel speed |

|

|

Cruising range |

|

|

Crew |

2092–2608 people |

|

Artillery |

8 (4x2) 380 mm SK/C-34 guns; |

|

Flak |

16 (8x2) 105 mm guns; 16 (8×2) 37 mm anti-aircraft guns; |

|

Aviation group |

2 catapults; 4 seaplanes |

"Bismarck" upon entry into service, 1940

"Bismarck" upon entry into service, 1940

Source – Bundesarchiv, Bild 101II-MN-1361–16A / Winkelmann / CC-BY-SA

At first glance, the artillery armament of the new battleship did not amaze the imagination: the main caliber was 8 380 mm guns in four turrets (the Germans were unable to create three-gun installations, or rather did not consider it necessary). Considering the fact that the Washington Naval Agreement of 1922 limited the caliber to 406 mm (the British and Americans had exactly these guns, installing 9-12 of them per ship), then the Bismarck does not look too intimidating.

380 mm SKC-34 gun as part of a coastal battery

380 mm SKC-34 gun as part of a coastal battery

Source – Schwerste Deutsche Küstenbatterie in Bereitschaft

However, the caliber of the SKC-34 gun was almost 100 mm larger than the caliber of the Scharnhorst guns (283 mm), and the excellent training of German artillerymen, high quality gunpowder, an advanced fire control system and modern sighting devices turned these gun mounts into world-class weapons. An 800-kg projectile was delivered over a distance of over 36 km with an initial speed of 820 m/s - this was enough to reliably penetrate 350 mm armor from a distance of about 20 km. Thus, in a functional sense, the SKC-34 guns were practically not inferior to the “top” 406 mm artillery.

The Bismarck's auxiliary artillery consisted of twelve 150 mm cannons in six twin turrets, sixteen 105 mm heavy anti-aircraft guns in eight twin turrets, as well as 37 and 20 mm anti-aircraft guns.

The battleship's power plant consisted of three turbo-gear units and twelve Wagner steam boilers. A power of 110 megawatts allowed the ship to reach a full speed of 30 knots.

"Bismarck" rolled off the stocks on February 14, 1939, and its retrofitting and testing continued until the spring of 1941. The first (and last) commander of the ship was Captain 1st Rank Ernst Lindemann.

Launching the Bismarck

Launching the Bismarck

Source - history.navy.mil

"Bismarck" during exercises in the Baltic Sea. The photo was taken from the cruiser Prinz Eugen, which will accompany the battleship on its last voyage.

"Bismarck" during exercises in the Baltic Sea. The photo was taken from the cruiser Prinz Eugen, which will accompany the battleship on its last voyage.

Source - waralbum.ru

"Bismarck" in service: the role of super-dreadnoughts in the Kriegsmarine battle plans

Almost simultaneously with the Bismarck, on February 24, 1941, the battleship Tirpitz of the same class was commissioned. By that time, the world war was raging for the second year, and the German “High Seas Fleet” had to confront, first of all, the British Navy. Thus, the steel giants Bismarck and Tirpitz found themselves in a very ambiguous position. In a one-on-one “knightly” battle, they could take on any ship in the world with a good chance of success. But such a battle in the conditions of World War II seemed unlikely and could most likely be the result of errors in planning.

Captain 1st Rank Ernst Lindemann

Captain 1st Rank Ernst Lindemann

Source –Bundesarchiv, Bild 101II-MN-1361–21A / Winkelmann / CC-BY-SA

At the same time, the two German giants and two “pocket” battleships were opposed by 15 British dreadnoughts and battlecruisers (5 more were under construction), among them were such powerful combat units as the battleship Hood with 381 mm artillery , quite comparable to the Bismarck. And, despite the fact that these enormous forces were dispersed over the vast expanses from the Pacific Ocean to the North Sea, the ratio was definitely not in favor of the German fleet.

The Kriegsmarine's combat planning prepared the new battleships for non-core tasks - the colossal dreadnoughts were planned to be used as... raiders. Their targets were not to be enemy warships, but transport convoys, liners and dry cargo ships. The cruising range of the battleships, which exceeded 8,000 nautical miles, fully corresponded to such tasks, and the speed of 30 knots became an outstanding achievement of German designers and shipbuilders.

Battleship Bismarck, modern reconstruction

Battleship Bismarck, modern reconstruction

Source - warwall.ru

At first glance, it may seem that targeting dreadnoughts at civilian and transport ships is unjustified - high-power guns should destroy armor, and not the thin sides of dry cargo ships. In addition, much cheaper ships could have been used for cruising war, especially since Germany had an impressive number of submarines and experience in their use. But this is only at first glance. The fact is that in a classic squadron battle, two German supergiants would be guaranteed to meet five or six “British” of comparable size, supported by a whole flock of smaller ships. At the same time, raiding communications, in addition to direct damage to the enemy’s economy, created enormous stress in the combat work of the enemy fleet. As the experience of the only raid of the Bismarck and the “walk” of the Tirpitz showed, the appearance of such a powerful ship on the cargo transportation routes forced the enemy to throw huge resources into its search, being distracted from urgent tasks, consuming scarce fuel and depreciating the vehicles. The indirect effect of such costs outweighed the possible damage that the Bismarck could inflict in open battle.

At the same time, the question remains open: why was it necessary to spend monstrous amounts of money on the construction of one of the most powerful ships in history, if two dozen submarines could do much more in terms of raiding? Today we can only consider the fact that the Bismarck raised her battle standard and went to sea.

Admiral Günter Lütjens, commander of Operation Rhineland Exercises

Admiral Günter Lütjens, commander of Operation Rhineland Exercises

The Hunt for Hitler's Dreadnought

On May 18, 1941, the battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen left the pier in Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland). On May 20–21, members of the Norwegian Resistance movement radioed about two large ships. On May 22, while stationed near Bergen, where the German ships were being repainted in camouflage and the Prinz Eugen was taking fuel, they were spotted by an English Spitfire reconnaissance aircraft, and the dreadnought was clearly identified as the Bismarck.

From that moment began one of the most impressive games in naval history. The Germans launched Operation Rhine Exercises to break through their squadron to Atlantic trade communications. In turn, the British fleet sought to destroy, or at least force the raiders to retreat. This was a fundamental moment for Great Britain - its economy was heavily dependent on sea supplies, to which the Bismarck became a mortal threat.

Admiral John Tovey, Commander of the Home Fleet

Admiral John Tovey, Commander of the Home Fleet

Source – Imperial War Museums

Admiral John Tovey, commander of the Home Fleet (which was responsible for territorial defense), ordered a search to begin. The battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Hood moved towards Iceland, and from Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland the battleship King George V with Admiral Tovey on board and the aircraft carrier Victorias set out - this squadron was assigned the task of patrolling to the northwest from Scotland, where the battlecruiser Repulse was to join her. At the same time, the light cruisers Arethusa, Birmingham and Manchester carried out patrols in the area from Iceland to the Faroe Islands, and the cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk took control of the Danish Straits.

On May 22, bombers were sent to Bergen, where the Bismarck was spotted, but they flew empty, not catching the squadron in place - the battleship seemed to have disappeared among the expanses of the sea. A day later, on May 23, Norfolk and Suffolk stumbled upon the German ships and exchanged several salvos with them, after which the British cruisers wisely retreated into the fog, continuing to follow the enemy at the limit of radar contact.

Despite the fact that his squadron was discovered, the commander of the Rhineland Exercises operation, Admiral Günther Lütjens, considered the intermediate task completed - the German ships confidently entered the operational space. However, in fact, the intermediate task was far from being completed, since the Hood and the Prince of Wales, accompanied by six destroyers, rushed towards the Germans from the coast of Iceland.

In the early morning of May 24, at 5:35 am, the Prince of Wales's patrol spotted the Bismarck. Vice Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland, holding the flag on the Hood, decided not to wait for the battleships of the Home Fleet and gave the order to approach. At 5-52, Hood opened the battle with the first salvos from a distance of 13 miles at sharp heading angles. Thus began the battle in the Denmark Strait.

Battlecruiser Hood

Battlecruiser Hood

Source - history.navy.mil

Lutyens had clear orders not to engage warships unless they were part of a convoy. However, Captain Lindeman categorically stated that he would not allow his battleship to be shot with impunity. According to eyewitnesses, his words sounded quite clear: “I won’t let my own ship get knocked out from under my own ass!” Prinz Eugen and Bismarck turned their turrets and fired back.

The Prinz Eugen with its 203-mm cannons could boast of the first hit - one of these shells hit the Hood. The British shots had no noticeable effect. At 0555, Holland ordered a 20-degree turn to port to engage the stern guns.

At about 6:00, when the Hood was completing its maneuver, the main battery of the Bismarck made a cover from a distance of about 8 miles. Apparently, the 800-kg shell broke through the rather thin deck of the British cruiser, hitting the ammunition depot. A monstrous explosion occurred, tearing the ship's 267-meter hull almost in half, while debris covered the battleship Prince of Wales, sailing half a mile behind. The stern of the Hood went under the water, and the bow remained above the waves for several more minutes, during which one of the towers managed to fire the last salvo. Of the 1,415 crew members, only three people survived, who were picked up by the destroyer Electra.

Sketch by the commander of the battleship "Prince of Wales" John Leach, attached to the protocol of the investigation into the death of the battlecruiser "Hood"

Sketch by the commander of the battleship "Prince of Wales" John Leach, attached to the protocol of the investigation into the death of the battlecruiser "Hood"

Source - wikipedia.org

The "Prince of Wales", which was sailing as a mate of the English squadron, was forced to turn away from its course to avoid a collision with the sinking "Hood" and thus exposed itself to the volleys of two German ships at once. Having received seven hits, the battleship left the battle under the cover of a smoke screen.

"Bismarck" fires

"Bismarck" fires

Source - waralbum.ru

The end of a short odyssey

Having sent one of Britain's best pennants to the bottom in just eight minutes, the Bismarck escaped with damage to two fuel tanks, and its boiler compartment No. 2 began to flood through a hole in the side. Vice Admiral Lutyens gave the order to go to the French Saint-Nazaire for repairs.

Despite the impressive victory, the situation for Bismarck was difficult. Firstly, due to the trim on the bow and starboard side, the speed decreased. Secondly, the hit to the tank deprived the battleship of 3,000 tons of fuel. Thirdly, the keen radars of the cruiser Suffolk continued to “guide” the Bismarck, which means that the English fleet could gather forces and strike again.

Already on the evening of May 24, nine Swordfish torpedo bombers from the aircraft carrier Victoria attacked the Bismarck, achieving one hit in the main armor belt, which, however, did not cause serious damage. However, active anti-torpedo maneuvering led to the failure of the patches, as a result of which the battleship lost boiler room No. 2, which was completely flooded.

The interception of the Bismarck after the destruction of the Hood, which shocked the entire British nation, became a matter of honor for the fleet. The search efforts, unprecedented in scope, had an effect, and on May 26, the Catalina seaplane found a German battleship 690 miles from Brest. Tactical Force “H” moved to the lead point under the command of Admiral James F. Somerville, the “hero” of the execution of the French fleet in Mers-el-Kebir. In addition, Admiral Tovey's battleships (Rodney and King George V) joined the connection.

Tovey miscalculated the course of the Bismarck, sending his ships to the shores of Norway. It should be noted that due to Tovey’s mistake, the closest pennants capable of giving battle to the Bismarck were 150 miles behind it, and only a miracle could stop the German breakthrough to Brest. And then the aircraft carrier “Ark-Royal” from Compound “N” said its weighty word. On May 26 at 17:40, fifteen Swordfish attacked the Bismarck. Archaic biplanes with a fabric-covered fuselage, an open cockpit and fixed landing gear, were armed with 730 kg torpedoes and had a very low speed. It seemed that this could not be a serious threat to the steel giant.

Torpedo bomber "Fairy Swordfish" - a deadly "wallet"

Torpedo bomber "Fairy Swordfish" - a deadly "wallet"

Source - wikipedia.org

“Swordfish,” which the pilots referred to only as “wallets,” had the ability to fly so low over the water that the Bismarck’s anti-aircraft gunners could not aim their guns at their targets. The battleship skillfully maneuvered, but one fatal torpedo still overtook it. A miracle happened.

A 730-kg torpedo in itself did not pose much of a threat to a super-dreadnought with a fantastic unsinkability system and thick armor. But by coincidence, it hit the most vulnerable spot - the steering blade. At one point, the huge ship lost control and could now maneuver only by stopping the screws. This meant an inevitable rendezvous with superior British forces.

"Swordfish" over the aircraft carrier "Ark Royal"

"Swordfish" over the aircraft carrier "Ark Royal"

Source - history.navy.mil

At 21-45, Bismarck entered into battle with the cruiser Sheffield, driving it away with fire. Following the Sheffield, the destroyers Cossack, Sikh, Maori, Zulu and Thunder approached, also failing to score any effective hits.

On May 27, at 8-00, Rodney, King George V, along with the cruisers Dorsetshire, Norfolk and several destroyers overtook Bismarck. The sea was rough - the sea level was 4-6, and Hitler's German super-dreadnought could only give a small speed of 8 knots and practically lost active maneuver, being an almost ideal target for nine 406-mm Rodney guns and a dozen 356-mm guns "King George" and sixteen 203-mm guns "Norfolk" and "Dorsetshire". The first shots rang out at 8:47 am.

Battleship Rodney

Battleship Rodney

Source – Imperial War Museums

The Bismarck concentrated its fire on the Rodney, which kept its distance. The British took the almost motionless German battleship into a classic artillery fork. Having taken aim at the bursts of undershoots and overshoots, the gunners of thirty-five large-caliber guns began to place shell after shell into the hull of the doomed ship. At 09:02, the Norfolk hit the main rangefinder post on the foremast with a 203-mm shell, which sharply reduced the quality of the Bismarck’s guns. Six minutes later, a sixteen-inch shell from the Rodney hit the forward turret B (Bruno), completely putting it out of action. Almost simultaneously with this, the fire control post was destroyed.

Around 09:20, the bow turret “A” was hit, presumably from the King George. Between 9-31 and 9-37 the stern towers “C” and “D” (“Caesar and “Dora”) fell silent, after which the battle finally turned into a beating. In total, the active firefight lasted about 45 minutes, with a predictable result - the Bismarck’s artillery was almost completely out of action.

Bismarck main caliber guns

Bismarck main caliber guns

Source – Imperial War Museums

“Rodney” approached and shot the enemy from a distance of 3 km, that is, almost point-blank. However, Bismarck did not lower the flag, continuing to snarl from the few remaining auxiliary caliber guns. One of the shots hit his wheelhouse, killing all the senior officers on the battleship. Apparently, Captain Lindeman also died then, although the surviving sailors claimed that he survived and continued to lead the battle until the very end. However, this no longer mattered - the huge ship turned into flaming ruins, and only its excellent survivability prevented it from immediately sinking to the bottom.

In total, the British fired more than 2,800 shells at the Bismarck, achieving about seven hundred hits of different calibers. For a long time there was an opinion that “Rodney” torpedoed “Bismarck” from a 620-mm apparatus, but modern underwater expeditions do not confirm this fact.

When the helplessness of the Bismarck became obvious to the British command, the battleships withdrew from the battle, leaving the cruisers to finish off with torpedoes. But even several direct hits on the underwater part of the German battleship did not lead to its sinking. The recent expedition of American director James Cameron on the Russian oceanographic ship Mstislav Keldysh clearly proved that enemy fire only significantly damaged the battleship. It was sunk by its own crew, who did not want to surrender the ship to the mercy of the victors.

Why did he drown?

Who exactly gave the order to scuttle the Bismarck, and whether there was such an order at all, is unclear. It is quite possible that there was a “local initiative”. In addition, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the fire from numerous fires led to the detonation of some of the ammunition, which led to the fatal hole. Cameron's research suggests open seams that were most likely torn apart by the bilge crew. Be that as it may, at 10:39 a.m. the Bismarck capsized and sank.

Of the 2,220 people on the Bismarck's crew, 116 survived. Among those rescued was a very remarkable character - the cat Oscar, who continued to serve in the British Navy. He was able to climb onto the floating debris and was pulled out of the water by the crew of the destroyer "Kazak". Subsequently, when the Cossack was sunk by a German torpedo, the cat moved first aboard the destroyer Legion, and then onto the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, whose planes destroyed his first ship (Bismarck). Later, the Ark Royal was lost off Malta, and Oscar found himself back on the destroyer Legion, much to the surprise of the crew. Earning the nickname "Unsinkable Sam", Oscar lived in Belfast after the war, where he died of natural causes in 1955.

The ship's cat Oscar, who survived the loss of three war pennants

The ship's cat Oscar, who survived the loss of three war pennants

Source - 24.media.tumblr.com

The fate of the Bismarck is very indicative. Firstly, the battle in the Denmark Strait once again showed the futility of developing ships without air cover. The obsolete Swordfish turned out to be a formidable opponent even for the newest and well-protected battleship with trained crews of numerous air defense guns. Secondly, a wave of personnel changes took place in Germany, which also affected the maritime strategy. Grand Admiral Erich Roeder lost his post as commander-in-chief, and was replaced by Karl Dönitz, an enthusiast and prominent theorist of unrestricted submarine warfare. Since then, German submarines have played the “first fiddle” in the raider war, and large ships have found themselves in secondary roles. The Bismarck remained lying on the seabed, still serving as a reminder: there are no unsinkable ships!

200 years ago, on April 1, 1815, the first Chancellor of the German Empire, Otto von Bismarck, was born. This German statesman went down as the creator of the German Empire, the “Iron Chancellor” and the de facto leader of the foreign policy of one of the greatest European powers. Bismarck's policies made Germany the leading military-economic power in Western Europe.

Youth

Otto von Bismarck (Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen) was born on April 1, 1815 at Schönhausen Castle in the Brandenburg Province. Bismarck was the fourth child and second son of a retired captain of a small landed nobleman (they were called Junkers in Prussia) Ferdinand von Bismarck and his wife Wilhelmina, née Mencken. The Bismarck family belonged to the ancient nobility, descended from the knights who conquered the Slavic lands on Labe-Elbe. The Bismarcks traced their ancestry back to the reign of Charlemagne. The Schönhausen estate has been in the hands of the Bismarck family since 1562. True, the Bismarck family could not boast of great wealth and was not one of the largest landowners. The Bismarcks have long served the rulers of Brandenburg in peaceful and military fields.

From his father, Bismarck inherited toughness, determination and willpower. The Bismarck family was one of the three most self-confident families of Brandenburg (Schulenburg, Alvensleben and Bismarck), they were called “bad, disobedient people” by Friedrich Wilhelm I in his “Political Testament”. My mother came from a family of government employees and belonged to the middle class. During this period in Germany there was a process of merging of the old aristocracy and the new middle class. From Wilhelmina, Bismarck received the alertness of the mind of an educated bourgeois, a subtle and sensitive soul. This made Otto von Bismarck a very extraordinary person.

Otto von Bismarck spent his childhood on the family estate of Kniephof near Naugaard, in Pomerania. Therefore, Bismarck loved nature and retained a sense of connection with it throughout his life. He received his education at the Plamann private school, the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium and the Zum Grauen Kloster Gymnasium in Berlin. Bismarck graduated from his last school at the age of 17 in 1832, having passed the matriculation exam. During this period, Otto was most interested in history. In addition, he was fond of reading foreign literature and learned French well.

Otto then entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied law. Study attracted little attention from Otto at that time. He was a strong and energetic man, and gained fame as a reveler and fighter. Otto took part in duels, various pranks, visited pubs, chased women and played cards for money. In 1833, Otto moved to the New Metropolitan University in Berlin. During this period, Bismarck was mainly interested, apart from “pranks,” in international politics, and his area of interest went beyond the borders of Prussia and the German Confederation, within the framework of which the thinking of the overwhelming majority of young nobles and students of that time was limited. At the same time, Bismarck had high self-esteem; he saw himself as a great man. In 1834, he wrote to a friend: “I will become either the greatest scoundrel or the greatest reformer of Prussia.”

However, Bismarck's good abilities allowed him to successfully complete his studies. Before exams, he visited tutors. In 1835 he received his diploma and began working in the Berlin Municipal Court. In 1837-1838 served as an official in Aachen and Potsdam. However, he quickly became bored with being an official. Bismarck decided to leave public service, which went against the will of his parents and was a consequence of his desire for complete independence. Bismarck was generally distinguished by his craving for complete freedom. The career of an official did not suit him. Otto said: “My pride requires me to command, and not to carry out other people’s orders.”

Bismarck, 1836

Bismarck the landowner

Since 1839, Bismarck has been developing his Kniephof estate. During this period, Bismarck, like his father, decided to “live and die in the countryside.” Bismarck taught himself accounting and agriculture. He proved himself to be a skillful and practical landowner who knew well both the theory of agriculture and practice. The value of Pomeranian estates increased by more than a third during the nine years that Bismarck ruled them. At the same time, three years fell during the agricultural crisis.

However, Bismarck could not be a simple, albeit intelligent, landowner. There was a power hidden within him that did not allow him to live peacefully in the countryside. He still gambled, sometimes in an evening he lost everything that he had managed to accumulate over months of painstaking work. He campaigned with bad people, drank, and seduced the daughters of peasants. He was nicknamed “mad Bismarck” for his violent temper.

At the same time, Bismarck continued his self-education, read the works of Hegel, Kant, Spinoza, David Friedrich Strauss and Feuerbach, and studied English literature. Byron and Shakespeare fascinated Bismarck more than Goethe. Otto was very interested in English politics. Intellectually, Bismarck was an order of magnitude superior to all the Junker landowners around him. In addition, Bismarck, a landowner, participated in local government, was a deputy from the district, deputy landrat and a member of the Landtag of the province of Pomerania. He expanded the horizons of his knowledge through travel to England, France, Italy and Switzerland.

In 1843, a decisive turn took place in Bismarck's life. Bismarck made acquaintance with Pomeranian Lutherans and met the fiancée of his friend Moritz von Blankenburg, Maria von Thadden. The girl was seriously ill and dying. The personality of this girl, her Christian beliefs and fortitude during her illness struck Otto to the depths of his soul. He became a believer. This made him a staunch supporter of the king and Prussia. Serving the king meant serving God for him.

In addition, there was a radical turn in his personal life. At Maria's, Bismarck met Johanna von Puttkamer and asked for her hand in marriage. Marriage to Johanna soon became Bismarck's main support in life, until her death in 1894. The wedding took place in 1847. Johanna gave birth to Otto two sons and a daughter: Herbert, Wilhelm and Maria. A selfless wife and caring mother contributed to Bismarck's political career.

Bismarck and his wife

"Raging Deputy"

During the same period, Bismarck entered politics. In 1847 he was appointed representative of the Ostälb knighthood in the United Landtag. This event was the beginning of Otto's political career. His activities in the interregional body of class representation, which mainly controlled the financing of the construction of the Ostbahn (Berlin-Königsberg road), mainly consisted of delivering critical speeches directed against the liberals who were trying to form a real parliament. Among conservatives, Bismarck enjoyed a reputation as an active defender of their interests, who was able, without delving too deeply into substantive argumentation, to create “fireworks”, distract attention from the subject of the dispute and excite minds.

Opposing the liberals, Otto von Bismarck helped organize various political movements and newspapers, including the New Prussian Newspaper. Otto became a member of the lower house of the Prussian parliament in 1849 and the Erfurt parliament in 1850. Bismarck was then an opponent of the nationalist aspirations of the German bourgeoisie. Otto von Bismarck saw in the revolution only the “greed of the have-nots.” Bismarck considered his main task to be the need to point out the historical role of Prussia and the nobility as the main driving force of the monarchy, and the defense of the existing socio-political order. The political and social consequences of the revolution of 1848, which engulfed large parts of Western Europe, had a profound impact on Bismarck and strengthened his monarchical views. In March 1848, Bismarck even planned to march with his peasants on Berlin to end the revolution. Bismarck occupied ultra-right positions, being more radical even than the monarch.

During this revolutionary time, Bismarck acted as an ardent defender of the monarchy, Prussia and the Prussian Junkers. In 1850, Bismarck opposed a federation of German states (with or without the Austrian Empire), as he believed that this unification would only strengthen the revolutionary forces. After this, King Frederick William IV, on the recommendation of King Adjutant General Leopold von Gerlach (he was the leader of an ultra-right group surrounded by the monarch), appointed Bismarck as Prussia's envoy to the German Confederation, in the Bundestag sitting in Frankfurt. At the same time, Bismarck also remained a deputy of the Prussian Landtag. The Prussian conservative debated so fiercely with the liberals over the constitution that he even fought a duel with one of their leaders, Georg von Vincke.

Thus, at the age of 36, Bismarck took the most important diplomatic post that the Prussian king could offer. After a short stay in Frankfurt, Bismarck realized that further unification of Austria and Prussia within the framework of the German Confederation was no longer possible. The strategy of the Austrian Chancellor Metternich, trying to turn Prussia into a junior partner of the Habsburg Empire within the framework of “Middle Europe” led by Vienna, failed. The confrontation between Prussia and Austria in Germany during the revolution became obvious. At the same time, Bismarck began to come to the conclusion that war with the Austrian Empire was inevitable. Only war can decide the future of Germany.

During the Eastern Crisis, even before the start of the Crimean War, Bismarck, in a letter to Prime Minister Manteuffel, expressed concern that the policy of Prussia, which fluctuates between England and Russia, if deviated towards Austria, an ally of England, could lead to war with Russia. “I would be careful,” noted Otto von Bismarck, “to moor our smart and durable frigate to an old, worm-eaten warship of Austria in search of protection from a storm.” He proposed to wisely use this crisis in the interests of Prussia, and not England and Austria.

After the end of the Eastern (Crimean) War, Bismarck noted the collapse of the alliance of the three eastern powers - Austria, Prussia and Russia, based on the principles of conservatism. Bismarck saw that the gap between Russia and Austria would last a long time and that Russia would seek an alliance with France. Prussia, in his opinion, had to avoid possible alliances opposing each other, and not allow Austria or England to involve it in an anti-Russian alliance. Bismarck increasingly took anti-British positions, expressing his distrust in the possibility of a productive union with England. Otto von Bismarck noted: “The security of England’s island location makes it easier for her to abandon her continental ally and allows her to abandon him to the mercy of fate, depending on the interests of English politics.” Austria, if it becomes an ally of Prussia, will try to solve its problems at the expense of Berlin. In addition, Germany remained an area of confrontation between Austria and Prussia. As Bismarck wrote: “According to the policy of Vienna, Germany is too small for the two of us... we both cultivate the same arable land...”. Bismarck confirmed his earlier conclusion that Prussia would have to fight against Austria.

As Bismarck improved his knowledge of diplomacy and the art of statecraft, he increasingly moved away from the ultra-conservatives. In 1855 and 1857 Bismarck made “reconnaissance” visits to the French Emperor Napoleon III and came to the conclusion that he was a less significant and dangerous politician than Prussian conservatives believed. Bismarck broke with Gerlach's entourage. As the future “Iron Chancellor” said: “We must operate with realities, not fictions.” Bismarck believed that Prussia needed a temporary alliance with France to neutralize Austria. According to Otto, Napoleon III de facto suppressed the revolution in France and became the legitimate ruler. Threatening other states with the help of revolution is now “England’s favorite pastime.”

As a result, Bismarck began to be accused of betraying the principles of conservatism and Bonapartism. Bismarck answered his enemies that “... my ideal politician is impartiality, independence in decision-making from sympathy or antipathy towards foreign states and their rulers.” Bismarck saw that stability in Europe was more threatened by England, with its parliamentarism and democratization, than by Bonapartism in France.

Political "study"

In 1858, the brother of King Frederick William IV, who suffered from a mental disorder, Prince Wilhelm, became regent. As a result, Berlin's political course changed. The period of reaction was over and Wilhelm proclaimed a "New Era", ostentatiously appointing a liberal government. Bismarck's ability to influence Prussian policy fell sharply. Bismarck was recalled from the Frankfurt post and, as he himself bitterly noted, sent “to the cold on the Neva.” Otto von Bismarck became envoy to St. Petersburg.

The St. Petersburg experience greatly helped Bismarck as the future Chancellor of Germany. Bismarck became close to the Russian Foreign Minister, Prince Gorchakov. Later, Gorchakov would assist Bismarck in isolating first Austria and then France, which would make Germany the leading power in Western Europe. In St. Petersburg, Bismarck will understand that Russia still occupies key positions in Europe, despite the defeat in the Eastern War. Bismarck studied well the alignment of political forces around the Tsar and in the capital’s “society”, and realized that the situation in Europe gives Prussia an excellent chance, which comes very rarely. Prussia could unite Germany, becoming its political and military core.

Bismarck's activities in St. Petersburg were interrupted due to a serious illness. Bismarck was treated in Germany for about a year. He finally broke with the extreme conservatives. In 1861 and 1862 Bismarck was twice presented to Wilhelm as a candidate for the post of Foreign Minister. Bismarck outlined his view on the possibility of uniting a “non-Austrian Germany.” However, Wilhelm did not dare to appoint Bismarck as minister, since he made a demonic impression on him. As Bismarck himself wrote: “He considered me more fanatical than I really was.”

But at the insistence of War Minister von Roon, who patronized Bismarck, the king nevertheless decided to send Bismarck “to study” in Paris and London. In 1862, Bismarck was sent as envoy to Paris, but did not stay there long.

To be continued…

Monuments to Bismarck stand in all major cities of Germany; hundreds of streets and squares are named after him. He was called the Iron Chancellor, he was called Reichsmaher, but if this is translated into Russian, it will turn out to be very fascist - “Creator of the Reich.” It sounds better - “Creator of an Empire”, or “Creator of a Nation”. After all, everything German that is in the Germans comes from Bismarck. Even Bismarck's unscrupulousness influenced the moral standards of Germany.

Bismarck 21 years old 1836

They never lie so much as during the war, after the hunt and before the elections

“Bismarck is happiness for Germany, although he is not a benefactor of humanity,” wrote the historian Brandes. “For the Germans, he is the same as for a short-sighted person - a pair of excellent, unusually strong glasses: happiness for the patient, but a great misfortune that he needs them.” .

Otto von Bismarck was born in 1815, the year of Napoleon's final defeat. The future winner of three wars grew up in a family of landowners. His father left military service at the age of 23, which angered the king so much that he took away the rank of captain and uniform from him. At the Berlin gymnasium, he encountered the hatred of the educated burghers towards the nobles. “With my antics and insults, I want to gain access to the most sophisticated corporations, but all this is child’s play. I have time, I want to lead my comrades here, and in the future, people in general.” And Otto chooses the profession not of a military man, but of a diplomat. But the career is not working out. “I will never be able to stand being in charge,” the boredom of an official’s life forces young Bismarck to commit extravagant acts. Biographies of Bismarck describe the story of how the young future Chancellor of Germany got into debt, decided to win back at the gambling table, but lost terribly. In despair, he even thought about suicide, but in the end he confessed everything to his father, who helped him. However, the failed social dandy had to return home to the Prussian outback and start running affairs on the family estate. Although he turned out to be a talented manager, through reasonable savings he managed to increase the income of his parents' estate and soon fully paid off all creditors. Not a trace remained of his former extravagance: he never borrowed money again, did everything to be completely independent financially, and in his old age was the largest private landowner in Germany.

Even a victorious war is an evil that must be prevented by the wisdom of nations

“I initially dislike, by their very nature, trade deals and official positions, and I do not at all consider it an absolute success for myself to even become a minister,” Bismarck wrote at the time. “It seems to me more respectable, and in some circumstances, more useful, to cultivate rye.” rather than writing administrative orders. My ambition is not to obey, but rather to command."

“It’s time to fight,” Bismarck decided at the age of thirty-two, when he, a middle-class landowner, was elected as a deputy of the Prussian Landtag. “They never lie so much as during the war, after the hunt and elections,” he will say later. The debates in the Diet capture him: “It is amazing how much impudence - compared to their abilities - the speakers express in their speeches and with what shameless complacency they dare to impose their empty phrases on such a large meeting.” Bismarck crushes his political opponents so much that when he was recommended for minister, the king, deciding that Bismarck was too bloodthirsty, drew up a resolution: “Fit only when the bayonet reigns supreme.” But Bismarck soon found himself in demand. Parliament, taking advantage of the old age and inertia of its king, demanded a reduction in spending on the army. And a “bloodthirsty” Bismarck was needed, who could put the presumptuous parliamentarians in their place: the Prussian king should dictate his will to parliament, and not vice versa. In 1862, Bismarck became the head of the Prussian government, nine years later, the first Chancellor of the German Empire. For thirty years, with “iron and blood” he created a state that was to play a central role in the history of the 20th century.

Bismarck in his office

It was Bismarck who drew up the map of modern Germany. Since the Middle Ages, the German nation has been split. At the beginning of the 19th century, residents of Munich considered themselves primarily Bavarians, subjects of the Wittelsbach dynasty, Berliners identified themselves with Prussia and the Hohenzollerns, Germans from Cologne and Munster lived in the Kingdom of Westphalia. The only thing that united them all was language; even their faith was different: Catholics predominated in the south and southwest, while the north was traditionally Protestant.

The French invasion, the shame of a swift and complete military defeat, the enslaving Peace of Tilsit, and then, after 1815, life under dictation from St. Petersburg and Vienna provoked a powerful response. The Germans are tired of humiliating themselves, begging, trading in mercenaries and tutors, and dancing to someone else's tune. National unity became everyone's dream. Everyone spoke about the need for reunification - from the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm and church hierarchs to the poet Heine and the political emigrant Marx. Prussia seemed to be the most likely collector of German lands - aggressive, rapidly developing and, unlike Austria, nationally homogeneous.

Bismarck became chancellor in 1862 and immediately declared that he intended to create a united German Reich: “The great questions of the era are decided not by majority opinion and liberal chatter in parliament, but by iron and blood.” First of all Reich, then Deutschland. National unity from above, through total submission. In 1864, having concluded an alliance with the Austrian emperor, Bismarck attacked Denmark and, as a result of a brilliant blitzkrieg, annexed two provinces populated by ethnic Germans from Copenhagen - Schleswig and Holstein. Two years later, the Prussian-Austrian conflict for hegemony over the German principalities began. Bismarck determined Prussia's strategy: no (yet) conflicts with France and a quick victory over Austria. But at the same time, Bismarck did not want a humiliating defeat for Austria. Bearing in mind the imminent war with Napoleon III, he was afraid of having a defeated but potentially dangerous enemy at his side. Bismarck's main doctrine was to avoid a war on two fronts. Germany forgot its history both in 1914 and 1939

Bismarck and Napoleon III

On June 3, 1866, in the battle of Sadova (Czech Republic), the Prussians completely defeated the Austrian army thanks to the crown prince’s army arriving in time. After the battle, one of the Prussian generals said to Bismarck:

- Your Excellency, now you are a great man. However, if the crown prince had been a little longer late, you would have been a great villain.

“Yes,” agreed Bismarck, “it passed, but it could have been worse.”

In the rapture of victory, Prussia wants to pursue the now harmless Austrian army, to go further - to Vienna, to Hungary. Bismarck makes every effort to stop the war. At the Council of War, he mockingly, in the presence of the king, invites the generals to pursue the Austrian army beyond the Danube. And when the army finds itself on the right bank and loses contact with those behind, “the most reasonable solution would be to march on Constantinople and found a new Byzantine Empire, and leave Prussia to its fate.” The generals and the king, convinced by them, dream of a parade in defeated Vienna, but Bismarck does not need Vienna. Bismarck threatens his resignation, convinces the king with political arguments, even military-hygienic ones (the cholera epidemic was gaining strength in the army), but the king wants to enjoy the victory.

- The main culprit can go unpunished! - exclaims the king.

- Our business is not to administer justice, but to engage in German politics. Austria's struggle with us is no more worthy of punishment than our struggle with Austria. Our task is to establish German national unity under the leadership of the King of Prussia

Bismarck's speech with the words "Since the state machine cannot stand, legal conflicts easily turn into issues of power; whoever has power in his hands acts according to his own understanding" caused a protest. Liberals accused him of pursuing a policy under the slogan “Might is before right.” “I did not proclaim this slogan,” Bismarck grinned. “I simply stated a fact.”

The author of the book "The German Demon Bismarck" Johannes Wilms describes the Iron Chancellor as a very ambitious and cynical person: There really was something bewitching, seductive, demonic about him. Well, the “Bismarck myth” began to be created after his death, partly because the politicians who replaced him were much weaker. Admiring followers came up with a patriot who thought only of Germany, a super-astute politician."

Emil Ludwig believed that "Bismarck always loved power more than freedom; and in this he was also a German."

“Beware of this man, he says what he thinks,” warned Disraeli.

And in fact, the politician and diplomat Otto von Bismarck did not hide his vision: “Politics is the art of adapting to circumstances and extracting benefit from everything, even from what is disgusting.” And having learned about the saying on the coat of arms of one of the officers: “Never repent, never forgive!”, Bismarck declared that he had been applying this principle in life for a long time.

He believed that with the help of diplomatic dialectics and human wisdom one could fool anyone. Bismarck spoke conservatively with conservatives, and liberally with liberals. Bismarck told one Stuttgart democratic politician how he, a spoiled mama's boy, marched in the army with a gun and slept on straw. He was never a mama's boy, he slept on straw only when hunting, and he always hated drill training

The main people in the unification of Germany. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (left), Prussian Minister of War A. Roon (center), Chief of the General Staff G. Moltke (right)

Hayek wrote: “When the Prussian parliament was engaged in one of the fiercest battles over legislation in German history with Bismarck, Bismarck beat the law with the help of an army that defeated Austria and France. If then only it was suspected that his policy was completely duplicitous, now this cannot be the case. to be in doubt. Reading the intercepted report of one of the foreign ambassadors he had fooled, in which the latter reported on the official assurances he had just received from Bismarck himself, and this man was able to write in the margin: “He really believed it!” - this master. bribery, who corrupted the German press for many decades with the help of secret funds, deserves everything that was said about him. It is now almost forgotten that Bismarck almost surpassed the Nazis when he threatened to shoot innocent hostages in Bohemia. The wild incident with democratic Frankfurt is forgotten. when he, threatening bombardment, siege and robbery, forced the payment of a colossal indemnity on a German city that had never taken up arms. It is only recently that the story of how he provoked a conflict with France - just to make South Germany forget its disgust with the Prussian military dictatorship - has been fully understood."

Bismarck answered all his future critics in advance: “Whoever calls me an unscrupulous politician, let him first test his own conscience on this springboard.” But indeed, Bismarck provoked the French as best he could. With cunning diplomatic moves, he completely confused Napoleon III, angered the French Foreign Minister Gramont, calling him a fool (Gramon promised revenge). The “showdown” over the Spanish inheritance came at the right time: Bismarck, secretly not only from France, but also practically behind the back of King William, offers Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern to Madrid. Paris is furious, French newspapers are raising hysterics about “the German election of the Spanish king, which took France by surprise.” Gramon begins to threaten: “We do not think that respect for the rights of a neighboring state obliges us to allow a foreign power to place one of its princes on the throne of Charles V and thus, to our detriment, upset the present balance in Europe and endanger the interests of and the honor of France. If this had happened, we would have been able to fulfill our duty without hesitation or flinching!” Bismarck chuckles: “It’s like war!”

But he did not triumph for long: a message arrived that the applicant refused. 73-year-old King William did not want to quarrel with the French, and the jubilant Gramont demands a written statement from William about the prince’s abdication. During lunch, Bismarck receives this encrypted dispatch, confused and incomprehensible, he is furious. Then he takes another look at the dispatch, asks General Moltke about the combat readiness of the army and, in the presence of the guests, quickly shortens the text: “After the Imperial Government of France received from the Royal Government of Spain official notification of the refusal of the Prince of Hohenzollern, the French Ambassador still presented in Ems to His Majesty the King demand that he authorize him to telegraph to Paris that His Majesty the King undertakes at all times never to give consent if the Hohenzollerns renewed their candidacy. Then His Majesty decided not to receive the French ambassador a second time and notified him through the aide-de-camp that His Majesty. there is nothing more to tell the ambassador." Bismarck did not write anything in or distort anything in the original text, he only crossed out what was unnecessary. Moltke, having heard the new text of the dispatch, noted admiringly that before it sounded like a signal for retreat, but now it sounded like a fanfare for battle. Liebknecht called such editing “a crime the likes of which history has never seen.”

“He led the French absolutely wonderfully,” writes Bismarck’s contemporary Bennigsen. “Diplomacy is one of the most deceitful activities, but when it is conducted in German interests and in such a magnificent way, with cunning and energy, as Bismarck does, it cannot be denied a share of admiration.” .

A week later, on July 19, 1870, France declared war. Bismarck achieved his goal: both the Francophile Bavarian and the Prussian Wurtenberger united in defending their old peace-loving king against the French aggressor. In six weeks, the Germans occupied all of Northern France, and at the Battle of Sedan, the emperor, along with an army of one hundred thousand, was captured by the Prussians. In 1807, Napoleonic grenadiers staged parades in Berlin, and in 1870, cadets marched along the Champs Elysees for the first time. On January 18, 1871, the Second Reich was proclaimed at the Palace of Versailles (the first was the empire of Charlemagne), which included four kingdoms, six great duchies, seven principalities and three free cities. Raising their bare checkers up, the winners proclaimed Wilhelm of Prussia Kaiser, with Bismarck standing next to the emperor. Now “Germany from the Meuse to Memel” existed not only in the poetic lines of “Deutschland uber alles”.

Wilhelm loved Prussia too much and wanted to remain its king. But Bismarck fulfilled his dream - almost by force he forced Wilhelm to become emperor.

Bismarck introduced favorable domestic tariffs and skillfully regulated taxes. German engineers became the best in Europe, German craftsmen worked all over the world. The French grumbled that Bismarck wanted to make Europe “a complete gamble.” The British pumped out their colonies, the Germans worked to provide for them. Bismarck was looking for foreign markets; industry was developing at such a pace that it was cramped in Germany alone. By the beginning of the 20th century, Germany overtook France, Russia and the USA in terms of economic growth. Only England was ahead.

Bismarck demanded clarity from his subordinates: brevity in oral reports, simplicity in written reports. Pathos and superlatives are prohibited. Bismarck came up with two rules for his advisers: “The simpler the word, the stronger it is,” and: “There is no matter so complicated that its core cannot be exhumed in a few words.”

The Chancellor said that no Germany would be better than a Germany governed by parliament. He hated liberals with all his soul: “These talkers cannot govern... I must resist them, they have too little intelligence and too much contentment, they are stupid and impudent. The expression “stupid” is too general and therefore inaccurate: among these people there are and intelligent, for the most part they are educated, they have a real German education, but they understand as little in politics as we did when we were students, even less, in foreign policy they are just children.” He despised socialists a little less: in them he found something of the Prussians, at least some desire for order and system. But from the rostrum he shouts at them: “If you give people tempting promises, with mockery and ridicule, declare everything that has been sacred to them until now is a lie, but faith in God, faith in our kingdom, attachment to the fatherland, to family , to property, to the transfer of what was acquired by inheritance - if you take all this away from them, then it will not be at all difficult to bring a person with a low level of education to the point where he finally, shaking his fist, says: hope be damned, faith be damned and above all, patience be damned! And if we have to live under the yoke of bandits, then all life will lose its meaning! And Bismarck expels the socialists from Berlin and closes their circles and newspapers.

He transferred the military system of total subordination to civilian soil. The vertical Kaiser - Chancellor - Ministers - Officials seemed to him ideal for the state structure of Germany. Parliament became, in essence, a clownish advisory body; little depended on the deputies. Everything was decided in Potsdam. Any opposition was crushed into dust. “Freedom is a luxury that not everyone can afford,” said the Iron Chancellor. In 1878, Bismarck introduced an “exceptional” legal act against the socialists, effectively outlawing the adherents of Lassalle, Bebel and Marx. He calmed the Poles with a wave of repressions; in cruelty they were not inferior to those of the Tsar. The Bavarian separatists were defeated. With the Catholic Church, Bismarck led the Kulturkampf - the struggle for free marriage; the Jesuits were expelled from the country. Only secular power can exist in Germany. Any rise of one of the faiths threatens a national split.

Great continental power.

Bismarck never rushed beyond the European continent. He said to one foreigner: “I like your map of Africa! But look at mine - This is France, this is Russia, this is England, this is us. Our map of Africa lies in Europe.” Another time he said that if Germany were chasing colonies, it would become like a Polish nobleman who boasts of a sable fur coat without having a nightgown. Bismarck skillfully maneuvered the European diplomatic theater. "Never fight on two fronts!" - he warned the German military and politicians. The calls, as we know, were not heeded.

“Even the most favorable outcome of the war will never lead to the disintegration of the main strength of Russia, which is based on millions of Russians themselves... These latter, even if they are dismembered by international treatises, are just as quickly reunited with each other, like particles of a cut piece of mercury. This is an indestructible state the Russian nation, strong with its climate, its spaces and limited needs,” wrote Bismarck about Russia, which the chancellor always liked with its despotism and became an ally of the Reich. Friendship with the Tsar, however, did not prevent Bismarck from intriguing against the Russians in the Balkans.

Decrepit by leaps and bounds, Austria became a faithful and eternal ally, or rather even a servant. England anxiously watched the new superpower, preparing for a world war. France could only dream of revenge. In the middle of Europe, Germany, created by Bismarck, stood as an iron horse. They said about him that he made Germany big and the Germans small. He really didn't like people.

Emperor Wilhelm died in 1888. The new Kaiser grew up an ardent admirer of the Iron Chancellor, but now the boastful Wilhelm II considered Bismarck's policies too old-fashioned. Why stand aside while others share the world? In addition, the young emperor was jealous of other people's glory. Wilhelm considered himself a great geopolitician and statesman. In 1890, the elderly Otto von Bismarck received his resignation. The Kaiser wanted to rule himself. It took twenty-eight years to lose everything.

The collector of German lands, the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck, was a great German politician and diplomat. The unification of Germany in 1871 was completed with his tears, sweat and blood.

In 1871, Otto von Bismarck became the first Chancellor of the German Empire. Under his leadership, Germany was unified through a “revolution from above.”

This was a man who loved to drink, eat well, fight duels in his spare time, and make a couple of good fights. For some time, the Iron Chancellor served as Prussia's ambassador to Russia. During this time, he fell in love with our country, but he really didn’t like expensive firewood, and in general he was a miser...

Here are Bismarck's most famous quotes about Russia:

The Russians take a long time to harness, but they travel quickly.

Don't expect that once you take advantage of Russia's weakness, you will receive dividends forever. Russians always come for their money. And when they come, do not rely on the Jesuit agreements you signed, which supposedly justify you. They are not worth the paper they are written on. Therefore, you should either play fairly with the Russians, or not play at all.

Even the most favorable outcome of the war will never lead to the disintegration of Russia's main strength. The Russians, even if they are dismembered by international treatises, will just as quickly reunite with each other, like particles of a cut piece of mercury. This is the indestructible state of the Russian nation, strong with its climate, its spaces and limited needs.

It is easier to defeat ten French armies, he said, than to understand the difference between perfect and imperfect verbs.

You should either play fairly with the Russians, or not play at all.

A preventive war against Russia is suicide due to fear of death.

Presumably: If you want to build socialism, choose a country that you don’t mind.

“The power of Russia can only be undermined by the separation of Ukraine from it... it is necessary not only to tear off, but also to contrast Ukraine with Russia. To do this, you just need to find and cultivate traitors among the elite and, with their help, change the self-awareness of one part of the great people to such an extent that they will hate everything Russian, hate their family, without realizing it. Everything else is a matter of time.”

Of course, the great Chancellor of Germany was not describing today, but it is difficult to deny his insight. The European Union must stand on the borders with Russia. By any means. This is an important part of the strategy. It is not for nothing that the United States was so sensitive to these desperate vacillations of the Ukrainian leadership. Brussels has entered into this, its first significant geopolitical battle.

Never plot anything against Russia, because it will respond to every cunning of yours with its unpredictable stupidity.

This interpretation, more expanded, is common in RuNet.

Never plot anything against Russia - they will find their own stupidity for any of our cunning.

The Slavs cannot be defeated, we have been convinced of this for hundreds of years.

This is the indestructible state of the Russian nation, strong with its climate, its spaces and limited needs.

Even the most favorable outcome of an open war will never lead to the disintegration of the main strength of Russia, which is based on millions of Russians themselves...

Reich Chancellor Prince von Bismarck to Ambassador in Vienna Prince Henry VII Reuss

Confidentially

No. 349 Confidential (secret) Berlin 05/03/1888

After the arrival of the expected report No. 217 dated 28 last month, Count Kalnoki has a tinge of doubt that the officers of the General Staff, who assumed the outbreak of war in the fall, may still be wrong.

One could argue on this topic, if such a war would possibly lead to such consequences that Russia, in the words of Count Kalnoki, “will be defeated.” However, such a development of events, even with brilliant victories, is unlikely.

Even the most successful outcome of the war will never lead to the collapse of Russia, which rests on millions of Russian believers of the Greek confession.

These latter, even if they are subsequently corroded by international treaties, will reconnect with each other as quickly as separated droplets of mercury find their way to each other.

This is the indestructible State of the Russian nation, strong in its climate, its spaces and its unpretentiousness, as well as through the awareness of the need to constantly protect its borders. This State, even after complete defeat, will remain our creation, an enemy seeking revenge, as we have in the case of France today in the West. This would create a situation of constant tension for the future, which we would be forced to take upon ourselves if Russia decides to attack us or Austria. But I am not ready to take on this responsibility and be the initiator of creating such a situation ourselves.

We already have a failed example of the “Destruction” of a nation by three strong opponents,a much weaker Poland. This destruction failed for a full 100 years.

The vitality of the Russian nation will be no less; we will, in my opinion, have greater success if we simply treat them as an existing, constant danger against which we can create and maintain protective barriers. But we will never be able to eliminate the very existence of this danger.

By attacking today's Russia, we will only strengthen its desire for unity; waiting for Russia to attack us can lead to the fact that we will wait for its internal disintegration before it attacks us, and moreover, we can wait for this, the less we use threats to prevent it from sliding into a dead end.

f. Bismarck.

All the activities of the outstanding German politician, the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck, were closely connected with Russia.

A book was published in Germany “Bismarck. Magician of Power”, Propylaea, Berlin 2013 under authorship Bismarck biographer Jonathan Steinberg.

The popular science 750-page tome entered the list of German bestsellers. There is enormous interest in Otto von Bismarck in Germany. Bismarck stayed in Russia as the Prussian envoy for almost three years, and his diplomatic activities were closely connected with Russia all his life. His statements about Russia are widely known - not always unambiguous, but most often benevolent.

In January 1859, the king's brother Wilhelm, who was then regent, sent Bismarck as envoy to St. Petersburg. For other Prussian diplomats this appointment would have been a promotion, but Bismarck took it as an exile. The priorities of Prussian foreign policy did not coincide with Bismarck’s beliefs, and he was removed from the court further, sending him to Russia. Bismarck had the diplomatic qualities necessary for this post. He had natural intelligence and political insight.

In Russia they treated him favorably. Since during the Crimean War, Bismarck opposed Austrian attempts to mobilize German armies for war with Russia and became the main supporter of an alliance with Russia and France, who had recently fought with each other. The alliance was directed against Austria.

In addition, he was favored by the Empress Dowager, née Princess Charlotte of Prussia. Bismarck was the only foreign diplomat who communicated closely with the royal family.

Another reason for his popularity and success: Bismarck spoke Russian well. He began to learn the language as soon as he learned about his new assignment. At first I studied on my own, and then I hired a tutor, law student Vladimir Alekseev. And Alekseev left his memories of Bismarck.

Bismarck had a fantastic memory. After just four months of studying Russian, Otto von Bismarck could already communicate in Russian. Bismarck initially hid his knowledge of the Russian language and this gave him an advantage. But one day the tsar was talking with Foreign Minister Gorchakov and caught Bismarck’s eye. Alexander II asked Bismarck head-on: “Do you understand Russian?” Bismarck confessed, and the Tsar was amazed at how quickly Bismarck mastered the Russian language and gave him a bunch of compliments.

Bismarck became close to the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince A.M. Gorchakov, who assisted Bismarck in his efforts aimed at diplomatic isolation of first Austria and then France.

It is believed that Bismarck’s communication with Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov, an outstanding statesman and Chancellor of the Russian Empire, played a decisive role in the formation of Bismarck’s future policy.

Gorchakov predicted a great future for Bismarck. Once, when he was already chancellor, he said, pointing to Bismarck: “Look at this man! Under Frederick the Great he could have become his minister.” Bismarck studied the Russian language well and spoke very decently, and understood the essence of the characteristic Russian way of thinking, which greatly helped him in the future in choosing the right political line in relation to Russia.

However, the author believes that Gorchakov’s diplomatic style was alien to Bismarck, who had the main goal of creating a strong, united Germany. TO when the interests of Prussia diverged from the interests of Russia, Bismarck confidently defended Prussia's positions. After the Berlin Congress, Bismarck broke up with Gorchakov.Bismarck more than once inflicted sensitive defeats on Gorchakov in the diplomatic arena, in particular at the Berlin Congress of 1878. And more than once he spoke negatively and disparagingly about Gorchakov.He had much more respect forGeneral of the Cavalry and Russian Ambassador to Great BritainPyotr Andreevich Shuvalov,

Bismarck wanted to be aware of both the political and social life of Russia, so I read Russian bestsellers, including Turgenev’s novel “The Noble Nest” and Herzen’s “The Bell,” which was banned in Russia.Thus, Bismarck not only learned the language, but also became familiar with the cultural and political context of Russian society, which gave him undeniable advantages in his diplomatic career.

He took part in the Russian royal sport - bear hunting, and even killed two, but stopped this activity, declaring that it was dishonorable to take a gun against unarmed animals. During one of these hunts, his legs were so severely frostbitten that there was a question of amputation.

Stately, representative,two meters tall andwith a bushy mustache, a 44-year-old Prussian diplomatenjoyed great success with“very beautiful” Russian ladies.Social life did not satisfy him; the ambitious Bismarck missed big politics.

However, only one week in the company of Katerina Orlova-Trubetskoy was enough for Bismarck to be captured by the charms of this young attractive 22-year-old woman.

In January 1861, King Frederick William IV died and was replaced by former regent William I, after which Bismarck was transferred as ambassador to Paris.

The affair with Princess Ekaterina Orlova continued after his departure from Russia, when Orlova’s wife was appointed Russian envoy to Belgium. But in 1862, at the resort of Biarritz, a turning point occurred in their whirlwind romance. Katerina’s husband, Prince Orlov, was seriously wounded in the Crimean War and did not take part in his wife’s fun festivities and bathing. But Bismarck accepted. She and Katerina almost drowned. They were rescued by the lighthouse keeper. On this day, Bismarck would write to his wife: “After several hours of rest and writing letters to Paris and Berlin, I took a second sip of salt water, this time in the harbor when there were no waves. A lot of swimming and diving, dipping into the surf twice would be too much for one day.” Bismarck accepted I took this as a sign from above and did not cheat on my wife again. Moreover, King William I appointed him Prime Minister of Prussia, and Bismarck devoted himself entirely to “big politics” and the creation of a unified German state.

Bismarck continued to use Russian throughout his political career. Russian words regularly appear in his letters. Having already become the head of the Prussian government, he even sometimes made resolutions on official documents in Russian: “Impossible” or “Caution.” But the Russian “nothing” became the favorite word of the “Iron Chancellor”. He admired its nuance and polysemy and often used it in private correspondence, for example: “Alles nothing.”

One incident helped him penetrate into the secret of the Russian “nothing.” Bismarck hired a coachman, but doubted that his horses could go fast enough. "Nothing!" - answered the driver and rushed along the uneven road so briskly that Bismarck became worried: “You won’t throw me out?” "Nothing!" - answered the coachman. The sleigh overturned, and Bismarck flew into the snow, bleeding his face. In a rage, he swung a steel cane at the driver, and he grabbed a handful of snow with his hands to wipe Bismarck’s bloody face, and kept saying: “Nothing... nothing!” Subsequently, Bismarck ordered a ring from this cane with the inscription in Latin letters: “Nothing!” And he admitted that in difficult moments he felt relief, telling himself in Russian: “Nothing!” When the “Iron Chancellor” was reproached for being too soft towards Russia, he replied:

In Germany, I’m the only one who says “nothing!”, but in Russia – the whole people!

Bismarck always spoke with admiration about the beauty of the Russian language and knowledgeably about its difficult grammar. “It is easier to defeat ten French armies,” he said, “than to understand the difference between perfect and imperfect verbs.” And he was probably right.

The “Iron Chancellor” was firmly convinced that a war with Russia could be extremely dangerous for Germany. The existence of a secret treaty with Russia in 1887—the “reinsurance treaty”—shows that Bismarck was not above acting behind the backs of his own allies, Italy and Austria, in order to maintain the status quo in both the Balkans and the Middle East.

Rivalry between Austria and Russia in the Balkans meant that Russia needed support from Germany. Russia needed to avoid aggravating the international situation and was forced to lose some of the benefits of its victory in the Russian-Turkish war. Bismarck presided over the Berlin Congress devoted to this issue. The Congress turned out to be surprisingly effective, although Bismarck had to constantly maneuver between representatives of all the great powers. On July 13, 1878, Bismarck signed the Treaty of Berlin with representatives of the great powers, which established new borders in Europe. Then many of the territories transferred to Russia were returned to Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina were transferred to Austria, and the Turkish Sultan, filled with gratitude, gave Cyprus to Britain.

After this, a sharp pan-Slavist campaign against Germany began in the Russian press. The coalition nightmare arose again. On the verge of panic, Bismarck invited Austria to conclude a customs agreement, and when she refused, even a mutual non-aggression treaty. Emperor Wilhelm I was frightened by the end of the previous pro-Russian orientation of German foreign policy and warned Bismarck that things were moving toward an alliance between Tsarist Russia and France, which had become a republic again. At the same time, he pointed out the unreliability of Austria as an ally, which could not deal with its internal problems, as well as the uncertainty of Britain’s position.

Bismarck tried to justify his line by pointing out that his initiatives were taken in the interests of Russia. On October 7, 1879, he concluded a “Mutual Treaty” with Austria, which pushed Russia into an alliance with France. This was Bismarck's fatal mistake, destroying the close relations between Russia and Germany. A tough tariff struggle began between Russia and Germany. From that time on, the General Staffs of both countries began to develop plans for a preventive war against each other.

P.S. Bismarck's legacy.

Bismarck bequeathed to his descendants never to directly fight with Russia, since he knew Russia very well. The only way to weaken Russia according to Chancellor Bismarck is to drive a wedge between a single people, and then pit one half of the people against the other. For this it was necessary to carry out Ukrainization.

And so Bismarck’s ideas about the dismemberment of the Russian people, thanks to the efforts of our enemies, came true. Ukraine has been separated from Russia for 23 years. The time has come for Russia to return Russian lands. Ukraine will only have Galicia, which Russia lost in the 14th century and it has already been under anyone, and since then has never been free.That’s why Bendera’s people are so angry with the whole world. It's in their blood.

To successfully implement Bismarck's ideas, the Ukrainian people were invented. And in modern Ukraine, a legend about a certain mysterious people is being circulated - ukrah, who supposedly flew from Venus and are therefore an exceptional people. TO of course, none ukrov and Ukrainians in ancient times It never happened. Not a single excavation confirms this.

It is our enemies who are implementing the idea of the iron chancellor Bismarck to dismember Russia. Since the beginning of this process, the Russian people have already endured six different waves Ukrainization:

- from the end of the 19th century until the Revolution - in the occupied Austrians of Galicia;

- after the Revolution of 17 - during the “banana” regimes;

- in the 20s - the bloodiest wave of Ukrainization, carried out by Lazar Kaganovich and others. (In the Ukrainian SSR in the 1920s - 1930s, the widespread introduction of the Ukrainian language and culture. Ukrainization in those years can be considered as an integral element of the all-Union campaign indigenization.)

- during the Nazi occupation of 1941-1943;

- during the time of Khrushchev;

- after the rejection of Ukraine in 1991 - permanent Ukrainization, especially aggravated after the usurpation of power by Orangeade. The process of Ukrainization is generously financed and supported by the West and the United States.

Term Ukrainization is now used in relation to state policy in independent Ukraine (after 1991), aimed at the development of the Ukrainian language, culture and its implementation in all areas at the expense of the Russian language.

It should not be understood that Ukrainization was carried out periodically. No. Since the beginning of the 20s, it has been and is ongoing continuously; the list reflects only its key points.

It is generally accepted that Bismarck's views as a diplomat were largely formed during his service in St. Petersburg under the influence of the Russian vice-chancellor Alexander Gorchakov. The future “Iron Chancellor” was not very happy with his appointment, taking it for exile.