Biography of Emperor Trajan. Emperor Trajan: short biography, interesting facts, photos

(96-98), the insolence of the violent people in the state reached the level of insolence, which put the meek monarch in a dangerous position. The weak, indecisive Nerva was forced to adopt the energetic commander Marcus Ulpius Trajan and instructed him to restore order in the state and discipline in the army. If the unrest under Nerva had not been so strong, then the people would not have recognized Trajan as a desired savior and benefactor during the reign of Nerva.

“It is true that the shame of our time was great, the wound inflicted on the state was severe,” writes Pliny. – The sovereign and father of the peoples of Nerva was besieged, he was held captive; he, a philanthropic old man, was deprived of the power to keep people alive: the sovereign was deprived of freedom from the yoke, but if this was the only way to entrust you with the management of affairs, then I am almost ready to say that it was a blessing. The discipline of the army fell so that you [Trajan] could become its restorer; abominations were committed so that you could counter them with excellent deeds; The sovereign was forced against his will to allow the murder of several people, but this led to the fact that we were given a sovereign who did not submit to violence. “You,” Pliny addresses Emperor Trajan, “have long deserved to be declared the son and heir of the emperor, but we would not know how great the benefit you bring to the state if the emperor [Nerva] had adopted you earlier. For us to see this, the time had to come when it became clear to everyone that by accepting power, you do not receive mercy, but show it. The upset state rushed into your arms, you were given by the word of the emperor power that was ready to collapse.”

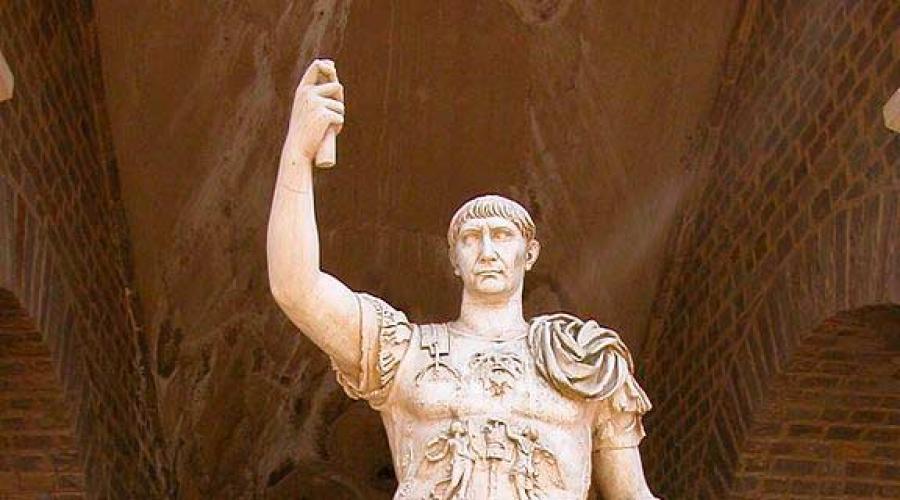

Roman Emperor Marcus Ulpius Trajan. Part of an antique statue

When Marcus Ulpius Trajan was adopted by Nerva, the people remembered an incident that served as an omen that he would become sovereign. One day Trajan thanked Jupiter Capitolinus for the victory won in Pannonia and placed a laurel wreath on the head of the statue; At the same time, the crowd shouted: “Hello, Emperor.”

Nerva's choice was truly excellent. Marcus Ulpius Trajan (ruled 98-117) did not belong by origin to the ancient Roman aristocracy; he was not even a native of Italy. Trajan's homeland was the Spanish colony of Italica (near present-day Seville). But Roman pride was already accustomed to submitting to many things that would previously have seemed unbearable to it, and the splendor that soon surrounded the name of the new emperor made one forget that he was not an ancient Roman aristocrat. However, the father of Mark Trajan already occupied the highest positions and was a famous commander. Trajan, during Nerva's lifetime, began to rule the state in such a way that everything in it quickly became the new kind. He placed the most arrogant people from the Praetorians in different legions, and the Praetorians resigned themselves.

Personality of Trajan

When Nerva died, Trajan was on the Rhine. Having received news of the emperor's death, he returned to Rome and took the imperial rank (99). Marcus Ulpius Trajan was then only 42 years old, but he was already gray-haired. By the choice of his assistants and friends, by his orders, by his concern for justice, honesty, the prosecution of vices, frugality, and strict supervision of the rulers of the province, he proved that with the good desires of Nerva, his personality was combined with a discerning mind and a strong will, that he would be an excellent sovereign, and when he began to wage war, he won victories and made conquests worthy of comparison with the great deeds of republican times. Trajan tried to reconcile freedom and imperial power, which no emperor after Augustus cared about before Nerva. He showed the same respect to the Senate as Nerva, raised the Senate from the humiliation into which it fell under Domitian. By his internal governance, respect for the law, love of education, meekness, civic virtues, the simplicity of his home life, alien to pompous etiquette and any luxury, Emperor Trajan earned the title of “Most Excellent” sovereign, and his military affairs, generally useful buildings and administrative talents acquired him the glory of the greatest of emperors. And if in many ways he was a son of his time, not completely free from vices and weaknesses, then his shortcomings were of little importance compared with his good qualities. If Trajan did not stop the persecution of Christians, he reduced it; and his pride was not a source of cruelty for him, like Nero and Domitian, but a motive to strive for deeds worthy of glory.

Statue of Emperor Marcus Ulpius Trajan from the German city of Xanten

There is no doubt that Emperor Trajan was always animated by the purest desires. They say that, knowing his weakness for wine, he ordered that those orders that he gives after the feast should not be immediately carried out; it is said that, presenting the sword, the emblem of the office entrusted to him, to the praetorian prefect, he said: “For me, when I am just; against me if I violate justice.”

Pliny eloquently praises the courage and other military prowess shown by the Emperor Marcus Ulpius Trajan in his very first campaigns - he says that, having been a military tribune, he had already discovered the talents of a commander, studied the art of war with his own experience in the camp and on campaigns, and taught him from his youth to endure hunger and thirst, heat and cold, shared all the hardships and labors of campaigns with ordinary soldiers, differed from the mass of them only by his extreme physical strength, walked in war and even on travel, usually on foot. With his cheerful courage, with which he endured all hardships, Trajan gained the love and surprise of the soldiers, and with his care for the food of the army, his attentiveness to the needs of the soldiers, his sincere disposition towards them and military talent, he earned their trust, - Pliny continues his panegyric to Emperor Trajan : “There are few people in the legions whose colleague you would not be. You know almost all of the old warriors by name, and in conversations with them you can recall the exploits of each one. They do not need to list to you the wounds they received, because you witnessed how they received them, and they already heard praise from you then.

Trajan's wars with the Dacian king Decebalus

Such a brave emperor as Trajan could not leave on the Roman name the shame to which the Dacians subjected him under the cowardly Domitian. The annual gift, which the Romans were obliged to give to the barbarians so that they would not attack the empire, and the money for which was collected by a heavy tax from the population of the Danube province, was completely in the nature of a tribute. Trajan stopped paying this gift; The Dacians started a war and invaded Mysia in order to take by force what was not being given to them peacefully. Trajan went against them (101). The first emperor, born not in Italy, but in the provinces, had to perform military feats so that the Roman mob and army would obey him.

The Dacian king Decebalus, an intelligent ruler and brave commander, who learned from his relations with the Romans to understand the benefits of civilization, made good use of the ten or twelve years of peace that had passed since the war against Domitian. Emperor Trajan met in the king of the Dacians an enemy who was well prepared for war; Decebalus defended himself strongly and withstood the struggle for four or even six years. Decebalus entered into alliances with neighboring tribes; he negotiated with the Parthian king Pacorus. In his service were Roman soldiers, artisans, engineers; Decebalus's army was trained and armed by them in the Roman way, they made weapons for him and built military vehicles.

The news about the Dacian campaigns of Emperor Trajan that have reached us is very scarce. Trajan's Column in Rome depicts scenes from the Dacian War, but they only give a general idea of it. The years and names of places remain unknown to us. It is only clear that in the first years the Romans crossed the Danube on ice, attacked the enemy, who did not expect to see them in their region in winter, defeated the Dacians in several battles, brought Decebalus to such an extreme that he begged Trajan on his knees to stop the war, promised to return conquered Roman lands, hand over deserters and Roman artisans, give away cars and weapons.

Battle of the Romans with the Dacians. Relief of Trajan's Column

“You defeated extremely brave peoples at a time of year that was favorable to them and difficult for us,” Pliny says to Emperor Trajan in his Panegyric. – When frost connects the banks of the Danube, and numerous troops can cross the river; when these savage tribes are protected not so much by their weapons as by the climate. But when you showed up, they locked themselves in their shelters, and our warriors, at your behest, joyfully followed this river, fought against the barbarians and their winter.” Trajan celebrated the triumph of victory in the war with the Dacians (103), and the Senate gave him the name "Dacian".

But the peace did not last. Trajan left garrisons on the northern bank of the Danube (in the present Banat and Military Frontier) and in the mountain passes that opened the way to the capital of the Dacian state, Sarmizegethusa, the extensive ruins of which are located near the present city of Vargeli. This clearly showed that Emperor Trajan wanted to keep power over Dacia in his hands. King Decebalus and the Dacian people were irritated and decided to try their military luck again; preparations for this were found in Rome to be a violation of the peace. By the will of the emperor, who wanted to gain the glory of the conqueror, the Senate declared the Dacians enemies of Rome. Trajan started a new war and went to the Danube (105). He built a stone bridge across it on 20 arches in the narrowest place of the river, where its flow is extremely fast - somewhat south of the gorge, which is now called Iron gates. He led his army across this bridge to Dacia.

When the water level is low, the bridge piers, made of large hewn stones, are still visible near Orshova. The bridge was built by the Greek architect Apollodorus of Damascus. It was considered an amazing structure, demonstrating that nothing is impossible for human art. Coins were struck in honor of its construction; several copies of them are in our collections. Trajan's successor, Emperor Hadrian, subsequently ordered the bridge decking to be removed, leaving only the bulls. On a nearby rock there is a carved inscription saying that Trajan continued the road along the right bank of the Danube, begun by Tiberius.

From the writings of the historian Dion, we know that Trajan, well aware of the dangers of campaigning through the Dacian country rugged by forests and swamps, waged the war very carefully, that his military talents and the courage of the legions were brilliantly displayed in it, and that victory required very great efforts. The Dacians had a belief in a future life and the transmigration of souls; it instilled in them contempt for death; they fought bravely, and their king Decebalus was a skilled commander, knew how to be cunning, and did not neglect treacherous tricks. One of the Roman commanders, Longinus, was captured and poisoned. But finally Trajan took the capital of the state and its citadel; Decebalus killed himself so as not to go captive in chains at the triumph of the enemy. The war is over. Dacia was conquered (107).

This was the first major war during the empire, waged to expand the borders of the state; therefore Pliny praises the intention of the poet Caninius to write a poem about her: “The subject is new, rich, vast, poetic, and the truth itself is like miracles; you will describe to us new rivers drawn by human hands, the construction of bridges, camps on steep mountains, you will talk about a king who lost his throne and life, but not his courage.”

Episode of the war with the Dacians. Relief of Trajan's Column

But almost no news has reached us about the details of this war with the Dacians. In addition to what we have already told, we only know that Trajan found treasures hidden by Decebalus in the river Sargetia (Strela or Istrige), on which his capital stood, that the conquered lands (Wallachia, Transylvania, Lower Hungary) were made a Roman province, which was called Dacia, and that Trajan settled there a great many colonists from different parts of the empire. Thus, the country lying between the Tisza, the Carpathians and the Danube was acquired for Roman culture. With the exception of a few swampy areas, it was very good: its plains were very fertile, its mountains rich in timber and metals. Soon populous cities arose in the country of the Dacians, such as Ulpia Trayana, Napoca (Maros Vasargeli), Dierna (Orshova). They were centers from which the habit of a peaceful, well-ordered life spread among the natives; Latin became the dominant language there (modern Romanian is derived from Latin). Industry and trade developed. The expansion of Trajan's borders brought the Roman Empire into contact with new enemies, the wild tribes of the north and east. The fight against them was often difficult, but the regions lying on the southern bank of the Danube, Mysia and Thrace, received very great benefits from the conquest of the Dacian country; they began to enjoy security, their well-being increased; and the warlike natives of Dacia supplied many brave warriors to the Roman legions.

Around the same time, Petraean Arabia was conquered by Aulus Cornelius Palma; Trajan annexed it to the empire under the name of the province of Arabia. The conquest of this strip of land, stretching from the Red Sea to Damascus, was important because it gave Palestine security from the raids of Arab tribes and freedom of trade routes from Syria to the Euphrates.

Trajan's buildings

The Dacian War spread the glory of the Roman emperor to very distant nations, whose ambassadors began to appear in Rome with congratulations to Trajan and offers of alliance. Trajan liked fame, and although he did not like either pomp or extravagance, he believed that, in connection with the victory, he should satisfy the passions of the population of the city of Rome for brilliant holidays and magnificent games.

Those books of Dion's “History”, which told about this and the next time, have not reached us. We have only a dry extract from them made by Xyphilin. It says: “Emperor Trajan gave spectacles that lasted one hundred and twenty-three days in a row; Up to 11,000 wild beasts and other animals were killed on them, and 10,000 gladiators fought. Foreign ambassadors were given places between the senators at these spectacles.”

For the glory of his victories over the Dacians and to decorate the city, Emperor Trajan erected (113) on a magnificent new square a colossal column, behind which his name is still preserved. He wanted his ashes to be buried under it; along it, in a spiral ribbon, there are reliefs depicting his exploits in Dacia. This magnificent monument, 110 feet high, still stands intact between the broken granite columns of Trajan's Forum. Inside the column, a twisted staircase leads to its top; there stood a colossal statue of the Apostle Peter.

Trajan's Column in the Roman Forum

But while making holidays for the people and erecting monuments to his glory, Emperor Trajan did not forget to build structures for public benefit. Since the time of Augustus, no emperor has built as many roads, bridges, and water pipelines as Trajan. The magnificent road that he built (106-110) through the Pomptine swamps and equipped with hotels for the rest of those passing through was more amazing than the roads built under the republic. New road from Brundisium to Beneventum was also worthy of the name of Trajan. He built roads and bridges not only in Italy, but also in the provinces; many traces of these structures of his remain in Spain and Germany. A continuous road was built from the Black Sea to Gaul. Trajan built, in addition to the bridge over the Danube, a beautiful stone bridge across the Rhine (near present-day Mainz), built bridges across many Italian and Spanish rivers, among other things, a bridge over the Tagus. In Rome, in Asia Minor, (in Prus and Nicomedia), in Egypt, and in other areas, he built water pipelines, baths, canals, and other structures that testify to his tireless activity. Huge structures in the harbors of Centumcell (Civitavecchia), Ostia, Ancona were worthy monuments to his name,

Emperor Trajan's love for buildings manifested itself, in addition to those mentioned by us, in several other magnificent buildings, decorating the city of Rome, where he built, among other things, a circus, an Odeon, and a gymnasium. His buildings excited both cities and private people to competition, Trajan patronized the builders, issued orders, favorable to this matter. The Roman Senate, the cities of Beneventum, Ancona, and many others built triumphal gates in his honor; he liked it. In general, he loved the buildings that perpetuated his fame. He gave his name to several newly built cities. The inscription “Ulpius Trajan” was found on so many buildings that Emperor Constantine called these words “the grass growing on all the walls” (herba parietaria). Trajan ordered the old worn-out coin to be re-minted; this may have been partly inspired by his desire to increase the number of coins bearing his image. And indeed, it came to us very a large number of his coins.

Reign of Trajan

With the same energy, Trajan cared about improving judicial proceedings, laws and administration. With help good lawyers, invited by him to serve, he issued a number of imperial constitutions on various departments of public and private life; These laws are generally reasonable and humane.

According to Pliny, Emperor Trajan during his reign issued wise and fair regulations on family and hereditary law, prohibited the acceptance of nameless accusations, passed sentences against absentees, abolished the purchase of positions and bribery of voters, prohibited candidates from giving feasts and gifts, obliged senators and dignitaries to have a third of his fortune in landed property, abolished trials in cases of lese majeste, expelled informers from Italy, in a word introduced a strong legal order and ensured that the laws were equally observed regarding nobles and ignorant. Trajan himself wrote to Pliny (X, 86): “You know my rule that I do not want to inspire respect for my name through fear and lese majeste trials.”

The noble, humane character of Emperor Trajan's reign was evident throughout his management of internal affairs and especially in his financial system. Almost all previous emperors oppressed the people with extortions to satisfy their extravagance; Trajan tried, through frugality, the simplicity of his court, and the elimination of all unnecessary luxury from his life, to obtain funds to make life easier for the poor classes.

At the very beginning of his reign, Trajan eased some taxes and duties - for example, duties on inheritances with close degrees of kinship; he appointed a special commission to study means of reducing government spending and always subordinated the benefits of the fiscus to the requirements of justice. During the reign of Trajan there were no confiscations, there were no wills in favor of the emperor, which were previously forced by fear, there were no other despotic measures to obtain money. He was actively concerned about benefits for the poor. Following the example of Nerva, Trajan extended the distribution of bread to the needy to Italian cities, and ordered children to be included in the lists of those receiving this benefit. It is said that every year 5,000 children of poor free people were accepted into state support. This was one of the means to stop the population decline in Italy. In matters of relief for the poor and the education of the children of the poor, Italy was divided into districts, and food banks were established. Children of warriors were probably especially accepted for public education, because Emperor Trajan cared most about the army; children raised for military service, of course, became good warriors. Military considerations also prompted the emperor to take care of improving highways; he also improved the post office to facilitate administrative communications and official travel. Trajan also cared a lot about improving urban government not only in Italy, but also in the provinces. He placed the free cities, which enjoyed almost complete independence in their internal affairs, under the supervision of imperial “trustees” (curatores or correctores).

After the army, Trajan's main concern was the spread of education. He founded a large library in Rome, founded at his own expense many educational institutions in which teachers received salaries and students enjoyed benefits; Cities and wealthy private people followed the emperor's example. We know that Pliny was an active imitator of Trajan in this matter. Through his efforts and with a significant financial contribution from him, the city of Kom, near which his estates lay, founded a school and a library. Emperor Trajan was not a man with a scientific education, but he knew how to appreciate science, loved the conversations of the gifted and learned people; therefore, the reigns of Trajan and his successor Hadrian constitute a brilliant period in the history of Roman and Greek literature. There were a lot of writers with him who enjoyed his favor and support.

One of his friends was the orator and statesman Pliny Secundus the Younger; Trajan gave him the consulate and made him ruler of Bithynia. In gratitude for this, Pliny delivered a Panegyric to Trajan at the Senate meeting, extolling the exploits and high qualities of the emperor. A large collection of reports and letters from Pliny to the emperor has reached us; they contain matters of all kinds, important and unimportant; Pliny constantly asks the emperor for decisions and advice. Tacitus was also one of Trajan's close friends. But our information about Trajan's reign is very scarce. The works of historians who spoke about him were lost. His memoirs about the Dacian War have not reached us. "History" by Tacitus was not brought to his reign.

Trajan's campaign against the Parthians

While taking care of the internal affairs of the state, Emperor Trajan did not forget the military. His pride was flattered by the thought of crossing the great rivers, which until then had been the borders of the Roman Empire. He wanted to eclipse the victories of Pompey and Caesar with his exploits, to avenge defeat of Crassus in Mesopotamia, wash away this stain of shame from the Roman name. After the death of Tiridates, a client of the Romans, whom they elevated to the Armenian throne, the Parthians, taking advantage of the disorder of the Roman Empire, subjugated Armenia, and its new king Exadar (it seems, the son of Tiridates) was dependent on the Parthians. Trajan did not like this; He was finally irritated by the fact that the Parthian king Khosroes I, son of Pacorus, overthrew Exadar and gave the Armenian throne to his nephew Parthomasirides. Emperor Trajan decided to stop the expansion of Parthian power with weapons. He went on a campaign (114); The Parthian embassy met him in Athens with gifts and assurances of Khosroes' friendship. But Trajan was filled with the desire to defeat the eastern people, whose name was associated for the Romans with such difficult memories. In his youth, he was on the borders of Parthia, accompanying his father, who fought there; now he wanted to show all his power to the distant East, to conquer the Parthian kingdom. The ambassadors of Khosroes did not reject Trajan from the war; on the contrary, he saw in the desire for peace on the part of the Parthians proof of their fear and weakness. Trajan accelerated the start of the campaign against the Parthians, answering the ambassadors that when he came to Syria, he would deal according to justice.

Among the ambassadors who greeted Emperor Trajan in Rome on his return from the Dacian War were ambassadors from “India.” So, his name has already become known in that distant country, where not a single European conqueror has penetrated since the campaign of Alexander and the first Seleucids. It is very possible that Trajan thought after the conquest of Parthia to go beyond the Indus. It seems that the Romans then awakened a new interest in the campaigns of Alexander. This is probably why I decided to describe them Arrian, whose youth coincides with the reign of Emperor Trajan.

Unfortunately, our information about the Parthian campaign of Trajan, as well as about the Dacian war, is very scarce. He came along the southern strip of Asia Minor to Antioch; During his stay there, this city was severely damaged by an earthquake, which endangered the life of the emperor himself. Abgar, king of Edessa (or Osroene) sent him rich gifts, asking permission to remain neutral. But Trajan forced the king of Edessa to submit. When he, continuing his campaign, entered Armenia, Parthomasirides thought to soften him with submission, laid a diadem at his feet, like Tigran at the feet of Pompey, hoping to get her back from his hands and remain the Armenian king under the rule of Rome. Trajan, however, announced that Armenia would be made a Roman province, which would be ruled by his governor. Parthomasirids fled and started a war. The Parthians were weakened by civil strife; Parthomasirides could not hold out for long against the Roman legions. His fortresses were taken, and he himself was killed in battle. Armenia was made a Roman province. The small kings of the mountainous lands between the Black and Caspian seas were in a hurry to express their submission to the Roman emperor, so as not to lose their possessions. Abgar's son, who liked Trajan, begged his father's forgiveness; Abgar received his kingdom back with the obligation to obey Rome.

We have only fragmentary dark news about the further events of Emperor Trajan’s campaign against the Parthians. From Dion we know that he, keeping his army in strict discipline and observing great caution, crossed the Gordian Mountains and, continuously fighting with enemies, passed through Mesopotamia, came through Nisibida to the Tigris, that in the mountain forests large boats were built, dismantled into pieces , transported to the Tigris, which, having made boats there again from pieces, Trajan swam across this fast river, walked along the eastern bank to the south, went to the places where Nineveh stood and where Alexander won a great victory over the Persians at Gaugemelae. The Parthians were busy with civil strife in their land, and Trajan, without encountering resistance, reached Babylon (116); from there he went east. He wanted to clear the silt-covered royal canal to restore navigation along it between the Tigris and Euphrates; but this work was so enormous that I had to give it up. Boats were dragged from the Euphrates on rollers to the Tigris; The Romans sailed them across the river again and took the Parthian capital Ctesiphon. Emperor Trajan conquered many other cities and lands in his campaign, says Dion; the Senate received so much news about the conquests that it no longer listed all these cities and regions, but gave Trajan the title of Parthian and decreed that the emperor would name at his triumph those peoples he wanted to name.

Trajan walked to the junction of the Tigris and Euphrates along the wide river they formed (Shatt al-Arab), sailed on ships into the “ocean” and expressed regret that his advanced years did not allow him to sail to India, like Alexander. He limited himself to making a sacrifice in honor of the memory of Alexander, and, having received news that many cities and tribes of the countries he had conquered had rebelled, he returned to pacify the revolts. Among the cities that rebelled were, according to Dion, Nisibida, Edessa and Seleucia, a large trading city in which Greeks and natives lived. One of Trajan's generals, Maximus, was defeated by the insurgents and lost his life in battle; but Trajan and his assistants, Lusius Quietus, Erucius Clarus and Julius Alexander, suppressed the rebellion, took Nisibida, Edessa, Seleucia, plundered and burned them. After that, Edessa and Seleucia could no longer recover; They were, however, renewed, but remained unimportant cities. Trajan went to Ctesiphon, declared Khosroes deposed there, proclaimed Parthamaspatas the Parthian king in his place, then moved against the Arabs, but fell ill during the siege of the Arab city of Gathras, which stood in Mesopotamia in the middle of the desert and defended itself bravely. The difficulties of the campaign and the hot climate of the waterless desert, devoid of any vegetation, so exhausted Emperor Trajan, an already old man, that he obeyed the requests of the Senate, which urged him to return. But he did not reach Italy. He died on August 11, 117 in the Cilician city of Selilunte (Trayanople), at the age of 64. His ashes were brought to Rome in a golden urn and buried under the column he had erected.

Such is the meager information given to us about Trajan’s Parthian campaign by Cassius Dio; in essential features they are consistent with the truth, as we see from the coins of Trajan, the images and inscriptions on which indicate that he conquered Armenia, Assyria, Mesopotamia, turned them into Roman provinces, and gave a king to the defeated Parthians. But these conquests were fragile. The Parthians very soon drove out the king appointed by Trajan and chose another. We see that the conquered regions and cities rebelled, without even waiting for Trajan to leave the East, destroyed the Roman troops left in them, and overthrew Roman power; returning from the south, he took, plundered and burned the rebel cities, but the natives remained hostile to him; the city of Gatra, in which there was a rich temple of the sun, could not be taken either by the emperor or by his commander Severus, who continued the siege.

Jewish War under Trajan (115–117)

During Trajan's Parthian campaign, the Jews rebelled in Alexandria, Cyprus, and Syria. These revolts began a new bloody Jewish war. The suppression of the Jewish uprising by Vespasian and Titus, the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple gave rise to irreconcilable hatred of the Romans among the Jews. The oppression in which the victors constantly kept the Jews thereafter increased Israel's enmity towards Rome, which stemmed from the opposition between their national character and their religion. Among the emperors of the Flavian dynasty, hatred of the Jews was a family feeling. The noble Titus, the strict Vespasian, and the fierce Domitian had it. The oppressed submitted to necessity with hidden bitterness, greedily awaiting the opportunity to take revenge on Rome. After the end of the Flavian dynasty, oppression softened. The tax paid by the Jews to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, which was heavy on their religious feelings, was abolished. The ban on Jews returning from flight from settling in the devastated Promised Land was also lifted. But shortly before Hadrian's accession, in the last years of Trajan's reign, a change occurred that was unfavorable to the Jews. During the war with the Parthians, Trajan became convinced that the Jews were ready to help all the enemies of Rome, considering it their national and religious duty to hate the Roman Empire. It was the same tribal antipathy between the Italians and the Semites that manifested itself in wars of Carthage with Rome.

Having entered into an alliance with the Parthians, the Jews raised terrible riots in the rear of Trajan's army. They flared up in places where there were many Jews (115–117): in Cyrene, in Upper and Lower Egypt, in Cyprus. “The feeling of philanthropy,” writes the great historian Edward Gibbon, - is especially indignant when reading stories about the disgusting cruelties committed by the Jews in the cities of Egypt, Cyprus and Cyrene, where, under the guise of friendship, they treacherously abused the trust of the native inhabitants, which is why we are inclined to approve of the Roman legions, who took severe revenge on the race of fanatics who as a result of her barbaric and frivolous prejudices, she became an implacable enemy not only of the Roman government, but of the entire human race. In Cyrene they killed 220 thousand, in Cyprus - 240 thousand Greek Christians, in Egypt - a huge number of inhabitants. Many of these unfortunate victims were sawn in two according to the precedent which was sanctioned by the example of David. The victorious Jews devoured the flesh of the unfortunates, licked their blood and girded themselves with their entrails.” The famous historian Theodor Mommsen paints a similar picture: “the uprising, although it was raised by the diaspora, was of a purely national character; in its main centers - in Cyrene, Cyprus, in Egypt - it had the goal of expelling the Romans and Hellenes and, apparently, the founding of a special Jewish state. The revolt spread all the way to the region of Asia and engulfed Mesopotamia and Palestine itself. Where the rebels gained the upper hand, they waged war with the same ferocity as the Sicarii in Jerusalem [in the First Jewish War], killing those whom they managed to capture; historian Appian, a native of Alexandria, tells how he, fleeing from them to save his life, barely escaped into Pelusium; They often killed their captives, subjecting them to painful torture... They said that in Cyrene they killed 220 thousand people in this way, and even 240 thousand people in Cyprus. On the other hand, in Alexandria, which apparently did not fall into the hands of the Jews, the besieged Hellenes killed all the Jews then in the city.”

These riots were pacified by Trajan's commanders Lusius Quietus and Marcius Turbon with that ferocity that dominates all wars when tribal bitterness is combined with religious hatred. In Cyprus, where the Jews destroyed Salamis and with inexorable fury exterminated the population of that city, the Romans took revenge on the stubborn rebels with the same inexorability; all the Jews were exterminated, and Jews from other places were forbidden to move to Cyprus. But this only temporarily stopped the fight between the Romans and the Jews. The reign of Trajan's successor, Hadrian, was marked by a new terrible Jewish war of 132-135. It was led by the bloody fanatic Bar Kochba.

Evaluation of Trajan's reign

Roman-Greek rule could not take root in the far East. The peoples of those countries stubbornly rebelled against him; but the more boastfully his reports, coins and monuments announced the victories of Emperor Trajan. The Parthian campaign was not free from failures, and in general it would be more prudent not to think about expanding the Roman state beyond its natural boundaries established by Augustus; it would be better to repeat the prayer Scipio Africanus the Younger, who asked the gods not to increase the state, but only to preserve with their mercy what had already been acquired by Rome; but still, the reign of Emperor Trajan is one of the most glorious and happiest periods in the history of the Roman Empire. Victories over foreign enemies introduced a fresh element into public life an empire inclined to decline from decrepitude; the campaigns did not so absorb the emperor’s activities that Trajan did not have time to worry about internal affairs: with the help of gifted advisers, he improved the administration and legal proceedings, took prudent measures to spread education and raise morality. The characterization of Trajan that Pliny made at the beginning of his reign, of course, contains a lot of flattering exaggeration, but, in essence, it is correct. “When I tried to formulate for myself the concept of a sovereign worthy of using unlimited power, similar to the power of the immortal gods,” says Pliny, “I could not even in my desires and thoughts imagine a sovereign similar to the one we see now. Many shone with glory in war, which faded during peace, others were good in peaceful affairs, but weak in war. Some gained self-respect, but inspired it with fear, others acquired love, but through humiliation. Some, having become sovereigns, lost the glory that they had earned as private people, while others, gaining glory as rulers, dishonored themselves with their private lives. In general, there was no sovereign whose good qualities were not overshadowed by the vices associated with them. But what a great combination of all qualities worthy of glory is found in our sovereign! His seriousness loses nothing from his gaiety, his dignity from his simplicity, his greatness from his condescension. His slender, strong physique, his expressive face, his venerable head, to which the gods gave gray hair in the prime of life, the beauty of old age - at one glance at him, everything shows him as a sovereign.”

Only an emperor like Trajan, who combined the energy of a warrior with a love for the affairs of the world, physical strength with moral strength, could give the empire a period of prosperity, the story of which Tacitus wanted to make a joyful occupation of his old age - a task that, unfortunately, he did not succeed in perform; only an emperor like Trajan could give the empire one of those rare happy periods when, in the words of Tacitus, “people have freedom to think and freedom to say what they think.” The Senate and the people were right in choosing the formula to greet the next emperors upon their accession to the throne: “Reign more happily than Augustus and better than Trajan!”

Marcus Ulpius Trajan was born in 53. He belonged to a family originally from the city of Tuder in Umbria, but his ancestors moved to Southern Spain. His father, also Marcus Ulpius Trajan, became the first famous senator from this family to achieve the post of consul. Nothing is known about the origins of the mother of the future emperor, Marcia.

For ten years Trajan was a military tribune and served in Syria, when in 75 his father became governor of this province. In 91 he became consul, and in 97 - governor of Upper Germany. At this time he was adopted by the emperor, which received approval from the soldiers and widespread support in Rome. When Nerva died in January 98, Trajan inspected the fortified area where the Danube and Rhine crossed, and arrived in Rome only after this inspection was completed.

With general approval of Nerva's choice, Trajan's long absence did not cause any unrest. Arriving in Rome in 99, he ascended the throne without any difficulty, received a triumph and canonized his named father among the gods. Strength of character allowed him to completely subjugate the Praetorian Guard.

Soon after taking the throne, Trajan created a secret military service to protect his power. For this purpose from the divisions frumentarians(grain supply agents) an information organization was formed and settled in the “foreign” camp ( Castra Peregrinorum ) on the Caelian Hill of Rome and established control posts on the roads outside the city. A mounted guard was also established (equites singulares ) numbering 500 people, where soldiers were carefully selected from the cavalry regiments of the allied tribes of Pannonia and Germany.

With the coming to power of Trajan, the international policy of the empire changed. Since the defeat of Varus in Germany, Roman troops had occupied a predominantly defensive position, not trying to offend their powerful neighbors. According to the new emperor, Rome lacked serious enemies for its development. The tribute with which Domitian bought peace with the Dacians was also humiliating. Immediately after his arrival in Rome, Trajan began to prepare to settle scores with them.

First of all, the payment of tribute was stopped. The ruler of Dacia, Decebalus, responded to this with a series of raids deep into the empire. Then, in 101, Trajan moved his troops eastward and in two years completely defeated Decebalus, forcing him to make peace and allow the establishment of Roman garrisons on his territory. This situation, in turn, became extremely humiliating for Decebalus and in 105 he again started a war, but again suffered a defeat so crushing that in a fit of despair he committed suicide.

First of all, the payment of tribute was stopped. The ruler of Dacia, Decebalus, responded to this with a series of raids deep into the empire. Then, in 101, Trajan moved his troops eastward and in two years completely defeated Decebalus, forcing him to make peace and allow the establishment of Roman garrisons on his territory. This situation, in turn, became extremely humiliating for Decebalus and in 105 he again started a war, but again suffered a defeat so crushing that in a fit of despair he committed suicide.

In 107, Dacia became a Roman province and quickly became Romanized, with the active creation of new colonies and cities on its territory. From that time on, every centimeter of land on the Mediterranean coast belonged to the Empire. This was her last major conquest. Neither before nor after the Roman Empire there was a moment in history when all these territories were under the rule of one person.

Now Romania is located on the territory of Dacia. the very name of which comes from Rome(Roma), and its population considers themselves descendants of colonists from the reign of Trajan. The Romanian language is related to Latin and has remained virtually unchanged over the past centuries.

In honor of the victory over the Dacians, a grandiose column was erected at the new forum, which has remained intact to this day. It is covered with spiral bas-reliefs telling the story of the Dacian campaigns, from preparations for war to the triumphant return of the emperor to Rome.

In honor of the victory over the Dacians, a grandiose column was erected at the new forum, which has remained intact to this day. It is covered with spiral bas-reliefs telling the story of the Dacian campaigns, from preparations for war to the triumphant return of the emperor to Rome.

The peace that followed did not last long. In 106 - 112, Trajan further expanded the borders of the empire to the east, forming the new province of Arabia with its capital in the city of Petra in the territory of modern Jordan. In addition, it was necessary to end once and for all the problem that Parthia had long represented. In 114, Trajan conquered Armenia, bordering Parthia, where the Parthian king Khosroes planted his puppet, and upper Mesopotamia.

Parthia by this time was weakened by civil wars, and Rome was experiencing a period of prosperity. The following year, Trajan took the Parthian capital Ctesiphon and advanced south to where the Tigris flows into the Persian Gulf. This was the furthest the Romans had ever managed to march to the east. According to historians, 60-year-old Trajan looked from the shore of the bay in the direction of India and sadly remarked: "If only I were younger..."

However, in 116, the Jewish diasporas rebelled simultaneously in several centers of the Middle and Near East. In addition to their dissatisfaction with the local authorities, they added the expectation of the coming of the Messiah, which exacerbated painful memories of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans. In addition, many of the Eastern Jews were outraged by the imposition of a tax on their communities ( fiscus Judaisus ) and sympathized with Parthia, believing that the arrival of the Romans would disrupt their trade ties.

Initially, the rebellion broke out in the Jewish community of Greek Cyrenaica and was brutally suppressed, but served as an impetus for armed civil strife between Jews and Greeks in Egypt on an unprecedented scale. The military leader Quintus Marcius Turbo, sent to suppress these unrest, was forced to also deal with the rebellion in Cyprus, where the rebels devastated the city of Salamis. The uprising that broke out in Judea itself was harshly suppressed by Lucius Quietus.

In Rome itself, paternalism and mercy reigned. The Emperor, following the example of his predecessor Nerva, continued to patronize poor children. The empire's birth rate was falling, creating the risk of a shortage of future soldiers to maintain order. With the help of benefits for poor families with children, Trajan hoped to avoid this threat. It should be noted that in those days the average mortality rate was significantly higher than today and the decline in the birth rate became a truly serious problem.

In Rome itself, paternalism and mercy reigned. The Emperor, following the example of his predecessor Nerva, continued to patronize poor children. The empire's birth rate was falling, creating the risk of a shortage of future soldiers to maintain order. With the help of benefits for poor families with children, Trajan hoped to avoid this threat. It should be noted that in those days the average mortality rate was significantly higher than today and the decline in the birth rate became a truly serious problem.

The decline in fertility in the Roman Empire is usually attributed to the selfish luxury of the upper classes and the apathy of the lower. But recently it was noted that the birth rate decline coincided major cities empires with the advent of central water supply. Water was supplied to houses through lead pipes, which resulted in chronic lead poisoning, which reduced the ability to bear children.

In governing the empire, Trajan adhered to traditional methods and respected the privileges of the Senate. The supply of grain was ensured and its free distribution guaranteed. The duties upon taking office, which subjects had paid to former emperors, ceased to be collected, and the taxation of the provinces was reduced, the governors of which began to be selected with special care. If control financial affairs in the provinces it got out of control, special administrators were appointed there, such as Pliny the Younger in Bithynia.

In one of his letters, Pliny asks the emperor how to treat the Christian sect. Trajan answers him: “You shouldn’t persecute them. Anyone who is accused and condemned to exile, if he says that he is not a Christian, and confirms this by his behavior - namely, the veneration of our gods - then, no matter what suspicion he has brought upon himself in the past, he deserves forgiveness by his repentance. . In addition, Trajan allowed Pliny not to respond to anonymous denunciations and canceled the search for Christians, trying to stop the process of spreading the new religion by eliminating unnecessary strictures.

Employment was provided by the ever-expanding public construction works, including a network of roads and bridges throughout the empire. The impressive Trajan Aqueduct, the last in the capital's water supply system, significantly improved the water supply to the citizens. This aqueduct was fed from springs near Lake Sabatine, stretched to the Janiculum Hill, directing water to the mills, and, crossing the Tiber, ended at Esquiline.

Aqueduct of Trajan

Aqueduct of Trajan On the Esquiline, near the former main residential wing of the Golden House of Nero, the baths of Trajan were built. They were opened in 109 two days before the aqueduct was put into operation. These baths were larger than all previous ones and became the first of the large 11 city baths. The huge main hall with a cross-shaped vault was surrounded by an area for cultural events. This complex monumental structure was the result of the work of the imperial architect Apollodorus of Damascus, a master of constructing structures held together with concrete.

Ruins of the Baths of Trajan

Ruins of the Baths of Trajan Apollodorus designed and, the last of the imperial forums, the most complex and significant. To erect it, it was even necessary to tear down part of it to the ground. The complex included Greek and Latin libraries, decorated with apses and colonnades of the Ulpius Basilica. In the open space stood a huge equestrian statue of the emperor. Of all this splendor, only dedicated to victory above the dacians there is a column.

Trajan Forum. Reconstruction

Trajan Forum. Reconstruction Adjacent to the northern part of the forum was Trajan's market. Its shopping arcades, rising in three terraces up the slope of the Quirinal and consisting of more than 150 shops, were built of concrete lined with heat-resistant bricks. Such bricks began to be used for external decorative finishing of buildings instead of marble and other stone.

Trajan's Market

Trajan's Market  Silver denarius. 103-111

Silver denarius. 103-111 The numerous slogans present on Trajan's coins reflected the emperor's desire to be a servant and benefactor of mankind. He tried to rule not as a master, but as princeps, the definition of the goals of which was given by Emperor Augustus. This corresponded to the special title of the emperor - Optimus , those. the best, and resembled the name of Jupiter himself -Optimus Maximus . This title was minted on a huge number of coins issued after 103.Senators of subsequent times, handing over power to the new emperor, wished him “to be happier than Augustus and better than Trajan” (felicior Augusto, melior Traiano ).

Under Trajan, the Roman Empire achieved the greatest prosperity in its history. In 116, Assyria and Mesopotamia became Roman provinces, and the eastern border of the empire ran along the banks of the Tigris. The state's lands were interconnected by 180,000 miles of roads and covered an area of approximately 3,500,000 square miles (the approximate area of the United States). The population of the empire was approaching 100,000,000 people, with about 1,000,000 of them living in Rome itself. The Empire was a large state even by modern standards.

Roman Empire in 117

Roman Empire in 117 In 116, an uprising swept the southern part of Mesopotamia. At the same time, the Parthians again gathered strength and attacked the Roman positions in Northern Mesopotamia and Armenia. The emperor restored order to some extent and even installed a puppet king on the throne in Ctesiphon, after which he went home, but he was unable to retain power. On the way to Rome, in 117, in the Cilician city of Selin, Trajan fell ill from an attack of dropsy, which ended in paralysis, and soon died.

Date: 106 A.D.

We are now entering the Christian era and can henceforth not mention “before” and “after” the Nativity of Christ, as we have done until now, in order to avoid confusion.

In 106, Emperor Trajan conquered Dacia. This country roughly corresponds to modern Romania. It was located north of the Danube - the border of the empire - and included the Carpathian mountain range.

The bas-reliefs of Trajan's Column in Rome depict the main episodes of this victorious campaign.

The new province of Dacia will be partially colonized by settlers from all parts of the empire, they will take Latin as their language of communication, and it will give rise to the Romanian language, the only Latin-based language of the eastern half of the empire. And this despite the fact that Greek culture predominated here.

Critical date

Why did we choose this date?

In the first century AD, the emperors continued the aggressive policy of the Republic, although not on such a scale as before.

Augustus captured Egypt, completed the conquest of Spain, and subdued the rebellious populations of the Alps, making the Danube the frontier of the empire.

To protect Gaul from barbarian invasions, he planned to conquer Germany, the territory between the Rhine and Elbe. At first he succeeds thanks to the defeat of his sons-in-law Drusus and Tiberius.

However, in 9 AD, the Germans rebelled under the leadership of Arminius (Hermann) and destroyed the legions of the legate Varus in the Teutoburg Forest. This catastrophe, which greatly worried Augustus (they say that he cried, repeating: “Var, give me back my legions”), forced him, like his heirs, to refuse to move the border along the Rhine. For more than two centuries, the Rhine and Danube (linked in the upper reaches between Mainz and Rotisbon by a fortified wall) formed the border of the empire in continental Europe. In 43, Emperor Claudius annexed Britannia (modern England), which became a Roman province.

The conquest of Dacia in 106 was the last major territorial acquisition of the Roman emperors. After this date, the boundaries remained unchanged for more than a century.

Roman world

The first two centuries of the empire, corresponding approximately to the first two centuries of our era, were a period of internal peace and prosperity.

Limes - systems of border fortifications along which legions stood - provided security, which made it possible to develop trade relations and the economy.

New cities are built and developed according to the model of Rome: they have an autonomous administration with a Senate and elected magistrates. But in reality, as in Rome, power belongs to the rich, not without certain responsibilities on their part. Thus, they must, at their own expense, build water pipelines, public buildings: temples, baths, circuses or theaters, and also pay for circus performances.

This Roman world cannot be idealized; the brutally exploited provinces often rebel. We saw this in Judea. But these uprisings are constantly suppressed by the Roman army.

While wealth and slaves flocked to Rome through conquest or forays on the borders, a certain economic and social balance was maintained.

When conquests ceased and attacks by “barbarians” (those who lived beyond the borders of the empire) became more frequent, an economic and social crisis rolled into Roman lands.

The “middle class” supplies fewer and fewer citizen soldiers, so the Roman army is increasingly replenished with mercenaries, often barbarian immigrants who receive Roman citizenship or a piece of land after their service.

After the reign of Augustus, imperial power became a stake in the struggle of rival armies located on various frontiers (on the Rhine, Danube and in the East), all too often called upon to march on Rome in order to install their commander on the throne. As a result of these internal disturbances, the borders are often left defenseless and exposed to barbarian attacks.

Crisis of the 3rd century

Difficulties begin during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161 - 180), emperor

a philosopher who in his “Thoughts” expounds humanistic philosophy. The peace-loving emperor is forced to spend most of his time repelling attacks on the borders of the state.

After his death, attacks from outside and internal unrest become more frequent.

In the 3rd century. a period called the Late Empire begins.

The edict of Emperor Caracalla (212), according to which all free inhabitants of the empire received Roman citizenship, becomes the starting point in the evolution of the gradual merging of the “provincials” and the Romans.

Between 224 and 228 The Parthian Empire fell under the blows of the Sassanids, the founders of the new dynasty of the Persian Empire. This state would become a dangerous enemy for the Romans - Emperor Valerian would be captured by the Persians in 260 and die in captivity.

At the same time, due to internal rebellions and political instability (from 235 to 284, i.e., in 49 years, 22 emperors were replaced), the barbarians penetrated the empire for the first time.

In 238, the Goths, a Germanic tribe, crossed the Danube for the first time and invaded the Roman provinces of Moesia and Thrace. From 254 to 259 another Germanic tribe, the Alemanni, penetrates Gaul, then Italy and reaches the gates of Milan. Previously open, Roman cities build protective walls, including Rome, where Emperor Aurelian begins in 271 the construction of a fortress wall, the first after the one that once existed in the Rome of the kings.

The economic crisis manifests itself in a monetary crisis: due to a shortage of silver, emperors mint coins of low standard, in which the content of the noble metal is sharply reduced. As the value of such money falls, price inflation occurs.

Diocletian (284–305) tries to save the empire by reorganizing it. Considering that one person cannot ensure the defense of all borders, he divides the empire into four parts: in Milan and Nicomedia there appear two emperors and two of their assistants - “Caesars”, they are the deputies and heirs of the emperors.

End of the Roman Empire

In 326, Emperor Constantine moved to Byzantium, a Greek city that controls the Bosphorus Strait, which connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. He gives this city his name, christening it Constantinople (the city of Constantine), and makes it the “second Rome.”

In 395, the Roman Empire was finally divided into the Western Roman Empire, which would disappear in 476 under the blows of the barbarians, and the Eastern Roman Empire, which would exist for another thousand years (until the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453). However, the latter will very soon become a country of Greek culture, and it will begin to be called the Byzantine Empire.

Trajan was the first emperor born outside of Rome. His family went back to the group of soldiers whom Scipio in 205 BC. e. moved to Italica Spain.

The father, Marcus Ulpius Trajan the Elder (?30 - up to 100), was supposedly the first in the family to achieve the senatorial status, under Nero. He was born in Spain to Roman settlers. His sister's name was Ulpia, who was the wife of the praetor Publius Aelius Hadrian Afra (father of the Roman Emperor Hadrian). In 60 he was appointed procurator of Baetica, possibly commanded a legion under Corbulo in the early 60s, in 67 he was appointed legate of the legion X Fretensis under the command of the then procurator of Judea Vespasian, from November 70 he served in Cappadocia, in the same year he received a consulate, and from the fall of 73 - in Syria, where he prevented an attempted Parthian invasion. In 79/80 he was proconsul of Asia. After his death in the year 100, he was deified, receiving the honorary title " divus Traianus pater».

Trajan's mother was Marcia (33-100), who was the daughter of the Roman senator Quintus Marcius Barea Sura and Antonia Furnilla. Her sister, Marcia Furnilla, was the second wife of Emperor Titus. Marcia's paternal grandfather was Quintus Marcius Barea, who was consul-suffect in 26 and twice proconsul of Africa, and her grandfather maternal line was Aulus Antonius Rufus, consul-suffect in 44 or 45. In 48, Marcia gave birth to Trajan's sister Ulpia Marciana. In honor of Marcia, Trajan founded a colony in North Africa, which was called Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi.

Trajan was born on September 15, 53 in the city of Italica, not far from Seville, where the Ulpii family owned considerable land. Trajan began his service as a coin triumvir in 74 ( triumvir monetalis), responsible for minting currency. Around this time he married Pompey Plotinus, a native of Nemausa (Narbonese Gaul). In 75 he became a laticlavian tribune in Syria, and two years later he was transferred to the same position in one of the legions stationed in Germany. In January 81, Trajan became quaestor, and in 86 - praetor. The following year he was appointed legate of the legion VII Gemina in Tarraconian Spain and in January 89 participated in the suppression of the uprising of Saturninus and his German allies the Hutts, for which he received a consulate in 91. Later, procuratorships followed in Lower Moesia and Upper Germany.

Internal power struggle

After the assassination of Domitian in 97, the aging Senator Nerva took the throne. Discontent in the army and the Praetorian Guard and the weakness of Nerves created the ground for political struggle in the Senate. At the very beginning of Nerva's reign, the Praetorians achieved the execution of Domitian's murderers. The Senate began to prepare for the death of the emperor, and Nerva lost a significant part of his powers. As a result, in October 97, an uprising of legionnaires broke out against Nerva, trying to enthrone a new emperor, already from among the soldiers. It was then that the real struggle for power began. At this time, two factions formed in the Senate, which tried to elevate their protege to Nerva's successor. One of the candidates, Nigrin Cornelius, was governor of the province of Syria, where one of the most powerful armies in the Roman Empire was located. Another group of senators leaned towards Trajan's candidacy. These senators were probably Sextus Julius Frontinus, Lucius Julius Ursus, Gnaeus Domitius Tullus, Lucius Licinius Sura and Titus Vestricius Spurianus. In the same year, Trajan was appointed procurator of Germania Upper and Moesia Inferior to counter the possible usurpation of Nigrinus. In this situation, realizing how weak his power was, Nerva (who was a lawyer) came up with a system that ensured the prosperity of the Roman Empire over the next century - according to it, the emperor (also called Augustus) had to appoint a successor and co-ruler (called Caesar) during his lifetime. . Moreover, the choice of Caesar had to be made regardless of kinship, but only according to his personal qualities. In order to consolidate the power of Caesar, he was adopted by Augustus. When the Praetorians captured the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill, Nerva was unable to save some of his officials. But he acted wisely, making Trajan his co-ruler and heir (that is, Caesar). According to Pliny's eulogy, it was divine inspiration.

In September 97, Trajan, while in Mogonziak after completing a successful campaign against the Suevi, received news from Hadrian that he had been adopted by Nerva. On the new year 98, Trajan was elected consul along with his de facto co-ruler Nerva. After 27 days, Hadrian, who arrived from Rome, informed Trajan, who was in the Colony of Agrippina, about the death of Nerva. Trajan received the title of emperor, and subsequently (October 25) proconsular (proconsulare imperium maius) and tribune (tribunicia potestas) power; in total, he was a tribune 21 times, but did not return to Rome immediately, deciding to temporarily remain in Germany. There Trajan was engaged in continuing to strengthen the borders between the upper Rhine and the Danube. In the spring, Trajan began to inspect the state of affairs on the Danube border, visiting Pannonia and Moesia, which suffered from the invasions of Rome’s longtime enemy Decebalus, and only in September of the following year he returned to Rome. There he made a triumphal entry into the city. A month later, Trajan distributed the first congiarium - a monetary reward to each citizen in honor of his assumption of office.

Appearance and personal qualities

Trajan was tall and had a good physique. His face was characterized by a concentrated expression of dignity, enhanced by premature gray hair. Here is what Cassius Dio wrote about his habits:

« He stood out among everyone for his justice, courage and unpretentious habits... He did not envy anyone and did not kill anyone, but respected and exalted all worthy people without exception, without feeling hatred or fear towards them. He did not pay attention to slanderers and did not give vent to his anger. Selfishness was alien to him, and he did not commit unjust murders. He spent huge amounts of money both on wars and on peaceful works, and having done a lot of extremely necessary things to restore roads, harbors and public buildings, he did not shed anyone’s blood in these enterprises... He was close to people not only at hunting and feasts, but also in their works and intentions... He loved to easily enter the houses of townspeople, sometimes without guards. He lacked education in the strict sense of the word, but in essence he knew and was able to do a lot. I know, of course, about his passion for boys and wine. But if, as a result of his weaknesses, he committed base or immoral acts, this would cause widespread condemnation. However, it is known that he drank as much as he wanted, but at the same time maintained clarity of mind, and in his relationships with boys he did not harm anyone».

This is what Aurelius Victor says in his work “On the Caesars”:

Trajan was fair, merciful, long-suffering, and very faithful to his friends; So, he dedicated the building to his friend Sura: (namely) baths called Suransky. (9) He trusted so much in the sincerity of the people that, according to custom, handing over to the praetorian prefect named Suburanus the sign of his power - a dagger, he repeatedly reminded him: “I give you this weapon to protect me, if I act correctly, but if not, then against me." After all, the one who manages others must not allow himself to make even the slightest mistake. Moreover, with his self-control he softened his characteristic addiction to wine, from which Nerva also suffered: he did not allow orders given after long-drawn-out feasts to be carried out..

Military activities

Trajan made significant changes to the structure of the Roman army as a whole. Were created:

- legions II Traiana Fortis And XXX Ulpia Victrix(both at 105 for the second Dacian campaign, so that the total number of legions reached a maximum of 30 under the Empire);

- ala I Ulpia contariorum miliaria And Ulpia dromedariorum, consisting of war camels, several units of Romanized Dacians and 6 auxiliary cohorts of Nabataeans;

- new mounted guard ( equites singulares) initially numbering 500 people from the inhabitants of Thrace, Pannonia, Dacia and Raetia.

The so-called frumentarii were transformed into a reconnaissance formation based in the Foreign Camp ( Castra Peregrinorum). To strengthen the Danube border, the Trajan Wall was erected. 3 new positions have appeared in the medical service - medicus legionis, medicus cohortis And optio valetudinarii(legionary and cohort physician and head of a military hospital, respectively).

Dacian campaigns

Almost from the very beginning of his reign, Trajan, without hesitation, began to prepare for the Dacian campaign, designed to once and for all avert the serious threat that had long hung over the Danube border. Preparations took almost a year - new fortresses, bridges and roads were built in the mountainous regions of Moesia, and troops called from Germany and the eastern provinces were added to the nine legions stationed on the Danube. At the legion base VII Claudia Pia Fidelis Viminatia assembled a shock fist of 12 legions, 16 al and 62 auxiliary cohorts with a total number of up to 200 thousand people. After this, in March 101, the Roman army, violating the treaty of Domitian and dividing into two columns (the western one was commanded by Trajan himself), crossed the Danube along the pontoon bridge. These forces were opposed by approximately 160 thousand (including 20 thousand allies - Bastarns, Roxolans and, presumably, Boers) army of Decebalus. The Romans had to fight hard; the aggressor faced a worthy opponent, who not only resisted steadfastly, but also bravely counterattacked on the Roman side of the Danube.

In Tibisca the army united again and began to advance towards Tapi. The tapas were located on the approaches to the capital of Dacia, Sarmizegetusa, where in September a battle took place with the Dacians who put up stubborn resistance.

Having rejected Decebalus's request for peace, Trajan was forced to come to the aid of the attacked fortresses south of the Danube. There he experienced success - the procurator of Lower Moesia, Laberius Maximus, captured the sister of Decebalus, and the trophies captured after the defeat of Fuscus were won back without a fight. In February 102, a bloody battle took place near Adamklissi, during which Trajan ordered his own clothes to be torn into bandages. Almost 4 thousand Romans died. In honor of this Pyrrhic victory, monumental monuments, a huge mausoleum, a grave altar with a list of the dead and a small mound were erected in Adamklissi. A counter-offensive was launched in the spring, but the Romans, with considerable effort, drove the Dacians back into the mountains.

Trajan again rejected a repeated request for peace and already in the fall managed to approach Sarmizegetusa. Trajan agreed to the third attempt to negotiate, since his army by that time was exhausted in battle, but with conditions quite harsh for the Dacians. Although in the late autumn of 102 neither Trajan nor his commanders believed in the successful completion of the struggle. Nevertheless, a triumph was celebrated in December, and in order to be able to quickly transfer reinforcements to Dacia, Trajan ordered his civil engineer Apollodorus to build a grandiose stone bridge across the Danube near the fortress of Drobeta, but due to non-compliance with the agreement, its construction was accelerated, and the guard was entrusted to the legion Legion I "Italica" (legio I "Italica").

On June 6, 105, Trajan was forced to start a new campaign, but mobilized smaller forces - 9 legions, 10 cavalry, 35 auxiliary cohorts (in total - more than 100 thousand people) and two Danube flotillas. At the beginning of the war, another bridge was built across the Danube to quickly transport the legions to Dacia. As a result of the fighting, the Romans again penetrated the Orastie Mountains and stopped at Sarmizegetusa. The attack on the capital Sarmizegethusa took place in the early summer of 106 with the participation of legions Adiutrix II And IV Flavius Felixus and vexilations from the legion VI Ferratus. The Dacians repelled the first attack, but the Romans destroyed the water supply system in order to quickly take the city. Trajan besieged the capital, which had turned into a fortress. In July, Trajan took it, but in the end the Dacians set it on fire, and part of the nobility committed suicide to avoid captivity. The remnants of the troops, along with Decebalus, fled to the mountains, but in September they were overtaken by a Roman cavalry detachment led by Tiberius Claudius. Decebalus committed suicide, and Tiberius, cutting off his head and right hand, sent them to Trajan, who transferred them to Rome. By the end of the summer of 106, Trajan's troops suppressed the last pockets of resistance, and Dacia became a Roman province. Not far from Sarmizegetusa, the new capital of Dacia was founded - Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica. Settlers from the empire, mainly from its Balkan and generally eastern outskirts, poured into the newly conquered lands. Along with them, new religious cults, customs and language reigned in the new lands. The settlers were attracted by the riches of the beautiful region and, above all, by the gold discovered in the mountains. According to the late antique author John Lydas, who referred to the military physician Trajan Titus Statilius Crito, about 500 thousand prisoners of war were taken.

In the Dacian campaigns, Trajan managed to create a corps of talented commanders, which included Lucius Licinius Sura, Lucius Quietus and Quintus Marcius Turbo. The northern coast of Pontus (Black Sea) fell into the sphere of Roman influence. Control over the Bosporus and political influence over the Iberians were strengthened. The emperor's triumph took place in 107 and was grandiose. The games lasted 123 days, and more than 19,000 gladiators performed. The Dacian spoils amounted to five million pounds of gold and ten million of silver. Guests of honor from India added solemnity to the celebration.

Eastern Campaign

In the West, the empire reached its natural borders - the Atlantic Ocean, so Trajan shifted the center of gravity of his foreign policy to the East, where rich and strategically important areas, but not yet developed by Rome, continued to be preserved.

Immediately after completing the conquest of Dacia, Trajan annexed the Nabatean kingdom, taking advantage of the discord after the death of its last king, Rabel II. At the end of 106 or at the very beginning of 107, Trajan sent an army led by the Syrian legate Aulus Cornelius Palma Frontonianus, which occupied the capital of Arabia, Petra. Immediately after the annexation, Arabia was organized into a new province called Stony Arabia. The first governor of the province was Gaius Claudius Severus, who simultaneously served as commander Legio III Cyrenaica, transferred from Egypt. At the beginning of 111, Claudius Severus began construction via Nova Traiana- a road leading from south to north across Arabia. This road is still operational in Jordan. And to this day, experts are admired by the fact that it was drawn exactly along the border with the desert, that is, territory in which, by definition, life could not exist. In fact, this road determined a climatic zone convenient for human habitation and at the same time the border of the province and the Empire from the east. Trajan decided to make the capital of the new province in Bostra - the city was renamed Nova Traiana Bostra.

Disagreements with the old enemy Parthia in connection with candidates for the Armenian throne (Parthian protege was Parthamasiris, Roman - Axidar) became a catalyst for the preparation of the main phase of the campaign, during which bridgeheads for the offensive were conquered. After unsuccessful negotiations with the Parthian king Khosroes in October 112/113. Trajan left Italy, at the same time reinforcements from the Dacian garrisons were transferred to the East, so that in total 11 legions were aimed against Parthia.

On January 7, 114, Trajan arrived in Antioch to eliminate the unrest that arose after the Parthian raids, and later, through Samosata in the upper reaches of the Euphrates, he went to Satala, the gathering place of the northern group of troops. Rejecting Parthamasiris's formal recognition of Roman authority, Trajan quickly occupied the Armenian highlands. In the north, successful negotiations were started with Colchis, Iberia and Albania, which secured the eastern Black Sea region for the Romans. Having eliminated Parthian rule in the southeast of Armenia, the troops gradually occupied Atropatena and Hyrcania. In the fall, all regions of Armenia and part of Cappadocia were united into the province of Armenia.

In 115, Trajan launched an attack on northwestern Mesopotamia. The local princes, Khozroy's vassals, offered almost no resistance, since he was busy in the eastern part of the kingdom and could not provide them with any help. After the occupation of the main cities - Sintara and Nisibis - at the end of the year, Mesopotamia was also declared a province. While in Antioch for the second time, on December 13, 115, Trajan miraculously escaped during a devastating earthquake by jumping out of the window of a house and was forced to spend several days under open air at the hippodrome. The severe destruction of this rear base of the army made further action difficult, but in the spring of the following year the completion of the construction of a large fleet on the Euphrates marked the continuation of the campaign.

The armies moved along the Euphrates and Tigris in two columns, communication between them was apparently maintained through the old channels restored by Trajan. After the occupation of Babylon, the ships of the Euphrates army were transported overland to the Tigris, where the army united and entered Seleucia. Khosroes was practically unable to cope with internal strife, and the Parthian capital Ctesiphon was taken without much difficulty, as a result of which the king was forced to flee, but his daughter was captured. Later, Septimius Severus, after his Parthian campaign, humbly asked the Senate to award him the title " divi Traiani Parthici abnepos" - "great-great-grandson of the divine Trajan of Parthia."

Trajan achieved unprecedented success: another province was created in the region of Seleucia and Ctesiphon - Assyria, the Mezen kingdom was taken at the mouth of the Euphrates, and the flotilla went downstream to the Persian Gulf, and Trajan, who was warmly welcomed in the port city of Charax, began planning further advance to India. According to one legend, he went out to the sea and, seeing a ship sailing to India, praised Alexander the Great and said: “If I were young, I would undoubtedly go to India.”.

Provincial politics

Trajan granted Roman citizenship to residents of several cities in his native Spain. In the process of colonizing Dacia, Trajan resettled a large number of people from the Romanized world, since the indigenous population had thinned out significantly due to the aggressive wars of Decebalus. Trajan paid much attention to the gold mining industry and sent pirustians skilled in this matter to some developments. Already existing Roman centers, such as Petovion in Upper Pannonia or Raciaria and Escus in Lower Moesia, were elevated to the rank of colonies, a number of municipalities were formed, old cities, for example, Serdik, were systematically restored.

In the annexed Nabataean kingdom, due to its great strategic importance, no less rapid Romanization began. Just as on the Danube, construction of roads, fortifications and a surveillance system began immediately. Already under the first procurator Gaius Claudius Severus, the construction of connecting highways between the Red Sea and Syria began. The road from Akkaba through Petra, Philadelphia and Bostra to Damascus, which was a seven-meter-wide cobblestone road and one of the most important highways in the entire Middle East, was systematically repaired and guarded. In parallel with this highway, a layered surveillance system was built with small fortresses, towers and signal stations. Their task was to control the caravan routes and oases in the border zone and to monitor all caravan trade. A Roman legion was stationed in the city of Bostra (modern Basra), which defended the lands of the new province from attacks by nomads.

Uprisings

Despite the colossal successes achieved, back in 115, isolated Jewish uprisings initially began in the army rear. Many once again expected the coming of the Messiah, who could exacerbate separatist and fundamentalist sentiments. In Cyrenaica, a certain Andrei Luke defeated the local Greeks and ordered the destruction of the temples of Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Pluto, Isis and Hecate, Salamis in Cyprus was destroyed by the Jew Artemion, and mass riots began in Alexandria between Jews and Greeks. The tombstone of Pompey, who took Jerusalem, was practically destroyed. The Egyptian procurator Marcus Rutilius Lupus could only send a legion ( III Cyrenaica or XXII Deiotariana) to protect Memphis. To restore order in Alexandria, Trajan sent Marcius Turbon there with a legion VII Claudia and military courts, and to reconstruct the destroyed temples it was necessary to confiscate Jewish property. Lucius Severus landed in Cyprus.